In the very early hours of Thursday 17th January 1991, I was despatched as a young journalist on The Observer to the dealing rooms of Smith New Court, a worthy firm of stockbrokers in the City of London, to witness how the markets reacted to the outbreak of the first Gulf War against Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

A yellowing newspaper cutting shows I reported that, a little before 8am, Smith New Court’s chairman, Sir Michael Richardson watched prime minister John Major declare war on a TV monitor and then said:

“I had a nudge on the political line a little early, so I’ve been up all night. We have to keep things tightly under control.”

He did indeed say those words, but it’s not the whole story. Walking up to him on the dealing floor, I asked how we were positioned in the markets for war. Mistaking me for one of his dealers, my notes showed that he replied:

"Number 10 called me last night, so we could adjust our positions in oil. So we should be okay.”

It was a magnificent example of insider-dealing, in collusion with the government. A few minutes later a Smith New Court PR woman ran up to me to say that Sir Michael hadn’t meant that and even if he’d said it, I was a guest on the floor and everything said there was confidential.

Kuwait was always about oil. This was an insight into where the UK’s political and financial priorities lay. Richardson had been at the heart of Margaret Thatcher’s Government as an unofficial adviser to the Treasury. This was his dividend. Eventually he was to lose his dealing licence for making unsafe loans to an American entrepreneur. He died in 2003.

I’m reminded of this story today, Thursday 21st September, the United Nations’ International Day of Peace, because it reminds me of where governments’ priorities really lie, because these are the priorities that invariably threaten peace.

And it matters because over 300 people on board were subjected to unimaginable suffering as “human-shield” hostages.

I’m also reminded that only last week passengers and crew aboard British Airways Flight 149 are preparing legal action against the government for being treated as “disposal collateral”, as the aircraft was used to plant special forces in Kuwait in the early hours of 2nd August 1990, as Iraqi forces crossed the border.

Their claim is that the UK government and BA have “concealed and denied the truth for more than 30 years". The issue has come to a head now because documents released in 2021 show that the Foreign Office was warned of the invasion an hour before the plane touched down.

And it matters because over 300 people on board were subjected to unimaginable suffering as “human-shield” hostages over the following five months.

These stories have a common thread. Smith New Court, with the government’s help, was about money. The government, with BA’s help, was about protecting its Kuwait oil reserves. It’ll be proven that the lives of innocent people mattered much less against these priorities, if they win their case.

That should make us very angry indeed. The sheer hypocrisy of rhetoric that spoke of defending the people of Kuwait is one thing. The idea that they could simultaneously serve God and Mammon is quite another.

But it may be that just-war criteria have failed to keep up with the motivations of global late-capitalism.

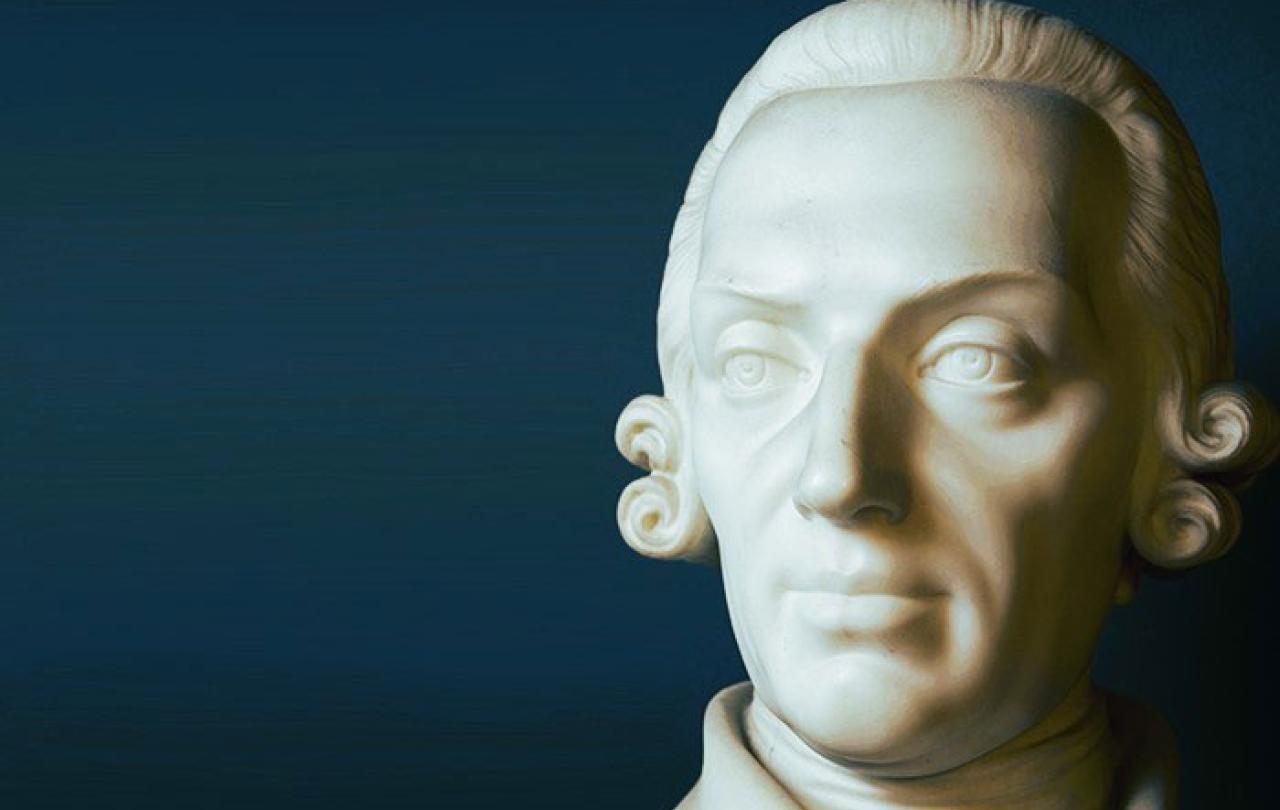

The principles of the “just war” have enjoyed a long tradition in Christian thought. The foundations that were laid in the classical Greek school by the likes of Aristotle were built upon to provide a moral architecture for armed conflict by the Italian Dominican friar and philosopher Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century.

The just war tradition distils into two sets of criteria: jus ad bellum (the right to go to war) and jus in bello (right conduct within war). The former set contains consideration of “just cause” and rules out war as a simple means of recapturing things or punishing people who have done wrong. The second includes matters of proportionality. By these clauses, combatants must ensure that harm caused to civilians or civilian property is not excessive in relation to military advantages gained.

In the second war with Iraq, an adventure that prime minister Tony Blair started with US president George W Bush in 2003, neither of these criteria arguably were met, along with others besides. To paraphrase Wilde, they knew the price of oil and values counted for nothing.

But it may be that just-war criteria have failed to keep up with the motivations of global late-capitalism. Economic dependence on oil is now more usually something we hear about in the context of the green movement’s war on the climate crisis. Dependence on oil actually has a firmer grip on political control of the cost of living in western democracies.

These are not issues that occurred to hot-shot stockbrokers playing war games in 1991, nor to a privatised national airline allegedly being requisitioned for military purposes. But it’s surely not too much to hope that the senior actors in either instance should have summoned at least a religious folk memory to say: No, this isn’t right.