The great English metaphysical playboy poet, John Donne, became Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1621. During Lent a year later he preached a majestic sermon entitled ‘To speake of Tears’. I first read it 30 years ago and it has prodded and challenged me ever since. This hyper-bright poet and reformed Lothario brought to the pulpit all his astonishing rhetorical skill, and a deep learning, combined with an overriding sense of God’s mercy and the wonder of new beginnings. His sermons were as thick as treacle and as rich as chocolate mousse, but built on a profound religious sympathy and a pastor’s ear for the yearnings of his listeners.

In his 1622 sermon, Donne highlights the different kinds of tears shed by Jesus in the last weeks of his life.

He speaks of Jesus’ ‘humane tears’ - tears he shed alongside Mary and Martha at the grave of his dear friend Lazarus - so surprising, Donne suggests, that the scholars charged with the chapter and verse divisions of the New Testament stopped in wonder at the two words ‘Jesus wept’ and made it a complete (and the shortest) verse in the Bible.

He speaks of Jesus’ ‘prophetic tears’ on Palm Sunday, as Jesus looks down over the city of Jerusalem, foreseeing the people’s rejection of God and the judgement that would come upon this city he loved. These tears are again surprising - Jesus had been borne into the city on the excited adulation of the crowds - so why does he weep?

Donne speaks of Jesus’ ‘pontifical’ or ‘sacrificial tears’ on the Cross - forsaken, despairing tears, encapsulated in Jesus’ agonisingly seizing a line of dereliction from the Psalms and hurling it at the dark sky - ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’

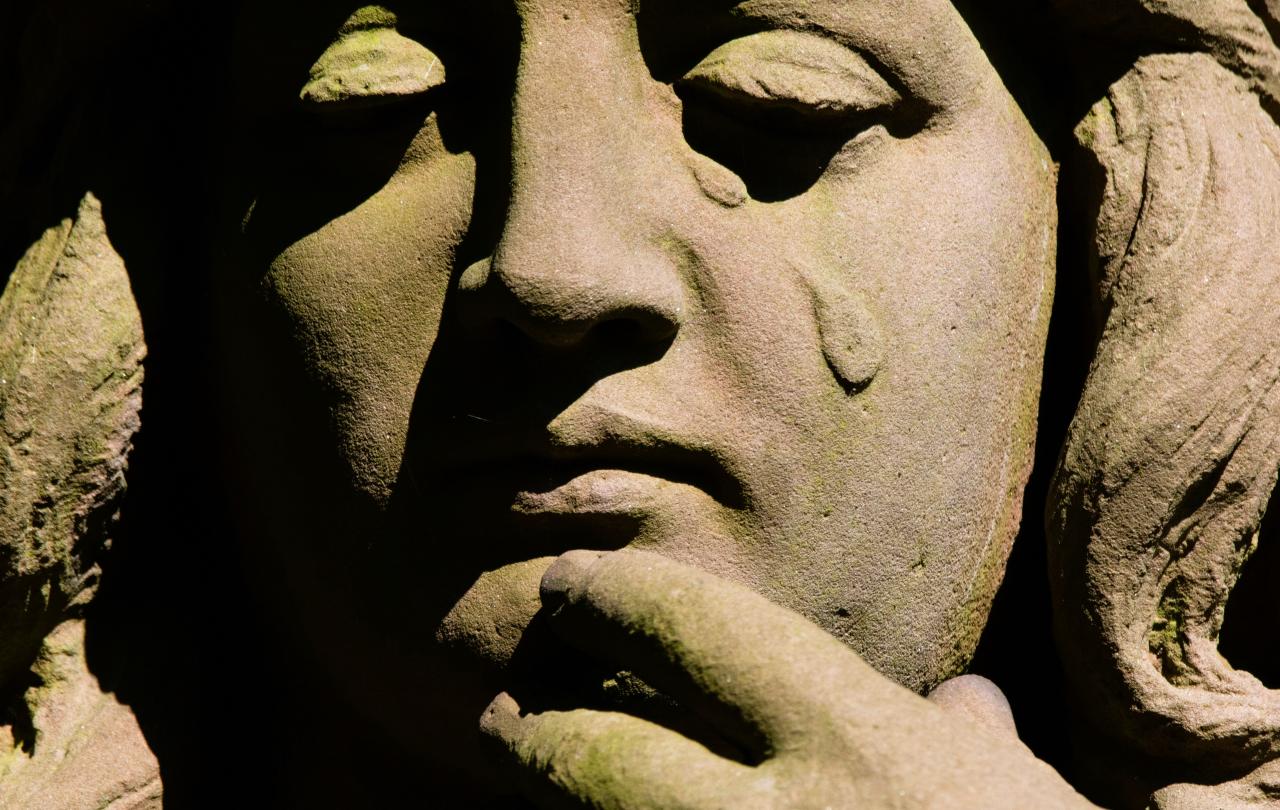

Donne was hardly the first theologian to wonder at these tears. But he is compelling in separating them out, wondering how different they are, and plotting the complexity of Jesus becoming a Man of Sorrows, for people who know so much sorrow. And he has the pastor’s touch as well as the preacher’s flourish to help us understand that we see ourselves most clearly through the tears of Jesus, or as C.S. Lewis would put it in the Problem of Pain, ‘the tears of God are the meaning of history.’

Tears, like snowflakes, are unique. Donne started to tease them apart 400 years ago, and we can see this even more clearly today, though it is always a challenge to do so because of the emotional intensity and maelstrom they spring from.

We now know there are physically three kinds of tears; basal tears, which lubricate the eye, irritant tears, which flush out bugs or specks of dirt and emotional tears, agreed by most to be unique to humans (though newborn babies don’t normally cry tears for the first month or more). Rose-Lynn Fisher poignantly deepened this understanding of different kinds of tears in her ground-breaking work on The Topography of Tears. As an artist, she captured some of her own tears and placed them on a microscope slide. She then took close-up pictures of the tears with a digital microscopy camera mounted on a 1960’s Zeiss standard light microscope;

‘The microscope provided the means to examine my tears and visually evoke the unseen realm of my emotions.’

She discovered that no two tears look the same, much as another hero of mine, Snowflake Bentley, had discovered, using a similar method in a frostier setting, the same is true for snowflakes. Tears of grief, even if shed at the same time, are all uniquely different; each one subtly changed by air temperature, and the proteins, minerals, hormones, antibodies and enzymes in an individual tear.

This knowledge brings a new weight to Jesus’ searching question to Mary on Easter morning - ‘Woman, why are you crying?’ These tears that I’m shedding, today, what kind of tears are these? Angry, grieving, frustrated, fearful? Fisher gives astonishing names to her close-ups of tears - ‘Compassion’, ‘Tears of Change’, ‘Overwhelm’, ‘Redemption.’ And it opens up the question of what tears am I not shedding? If there are so many different kinds of tears, are there some I am avoiding, or closing my heart to?

Richard Rohr has just published a long-awaited book on the Minor Prophets called The Tears of Things. I cannot possibly summarise it here, but Rohr includes an argument for the necessity of tears to soften our anger and outrage, the defining emotions of our age. He charts the prophet’s journey from outrage at the lawlessness of the world, through tears for the greed and cruelty of the world, to a settled but fiercer love and mercy. The prophetic tears of Jesus - tears of love, not for ourselves, but an expression of compassion for others - are the ultimate expression of this. This is a compelling vision - I would prefer the people who mould our world to be less shouty and angry, and more tearful and compassionate, people who live near enough to the pain of others to have cried with them and for them before making a plan.

The Psalms offer us a second discipline for our tears. As well as knowing them, that is understanding them, naming them, placing them, we can sow them:

‘Those who sow in tears

Will reap with songs of joy.’

This is an ancient invitation to give weight to our tears. To take them to God, to share them with others, and not just to see them as a way to get things of our chest.

Our human tears can deepen our sense of frailty and dependence on others and God.

Our prophetic tears can invigorate our fight for justice and peace, without destroying our spirit or making us worse than the people we criticise.

Our forsaken tears, the ones shed quietly, without hope, without even the hope that God sees them, can prepare the way for God’s new beginnings.