Sometimes it's just too hard to let it go. Art Garfunkel recently told The Times that he and Paul Simon have put aside their feud. Again. I was at their gig in Melbourne in 2009, four rows from the front. Although Art's voice soared, it faltered on Bridge Over Troubled Water. But it was glorious. Their setlist began with Old Friends, the name of their reunion tour, tragically describing a duo marked by both harmony and discord.

It's not just old friends who can harbour old grudges. It turns out, according to John Marzluff from the University of Washington, that crows can similarly prolong a grudge for up to 17 years. Putting aside a longstanding grudge can be a good commercial decision, as evidenced by a certain Britpop band recently... but when I heard on the radio the other morning that crows are good at holding grudges, I must admit it made me laugh. There's something about the pettiness, the silliness of human grudges that seem to befit the ridiculousness of a bird. The bird-brained behaviour of holding a grudge may similarly find its root in fear: just as Marzluff has discovered that crows' brains show evidence of human-like fear.

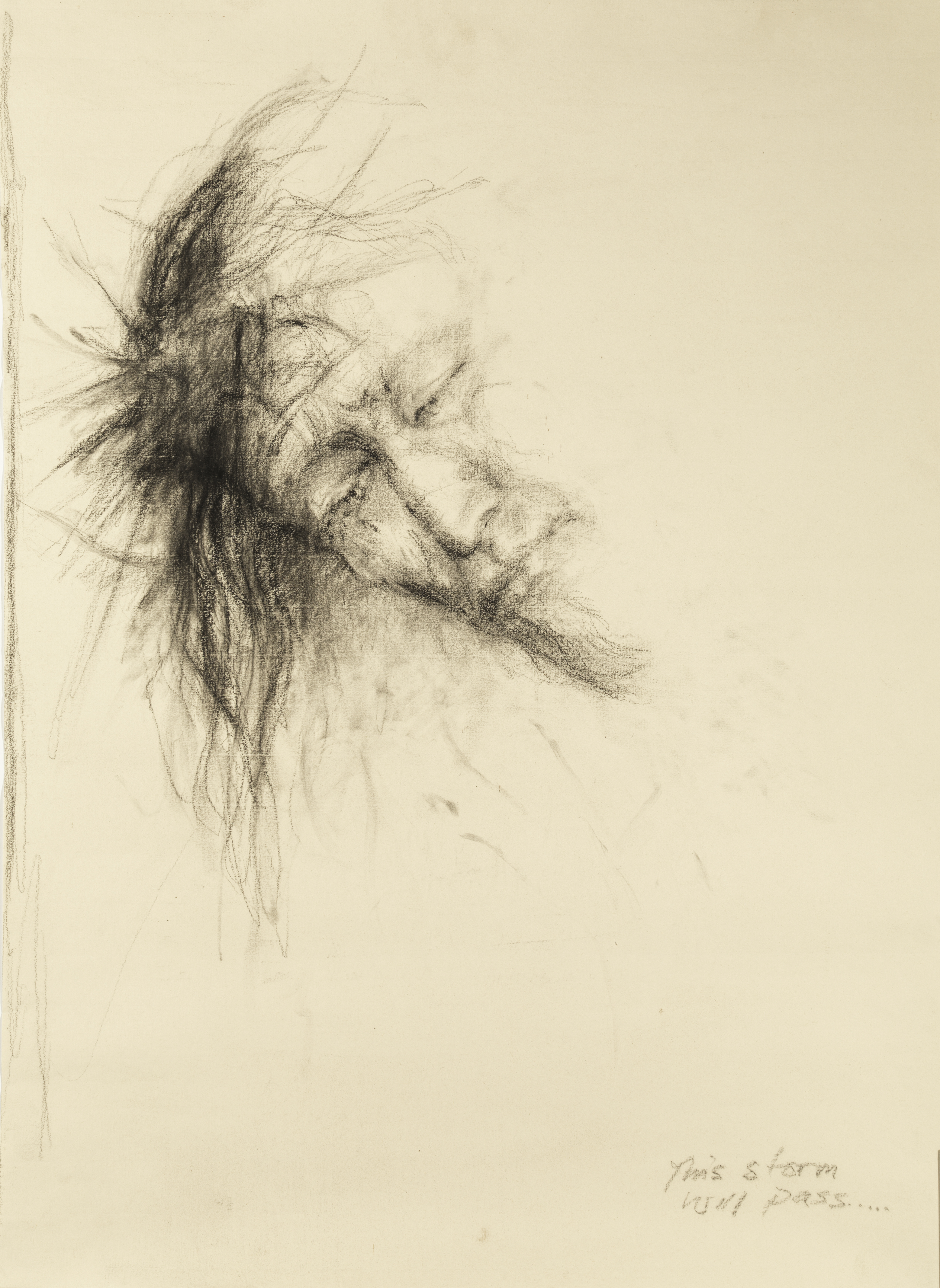

But grudges, just like fear, are no laughing matter. They aren't light, and they don't soar like crows or an ageing rocker's voice, but thud and squelch in all their onomatopoeic heft. We hold onto petty and significant grievances because, however unpleasant, we feel we have control. But the language we use around grudges is telling - we bear grudges, hold them, nurse them. Grudges, just like children, grow over time. And whether they last for weeks of crow-like decades… they destroy things around us and within us. Perhaps it's apt that the collective noun for a crow is 'murder'. Indeed, it's old wisdom that such grudges are destructive. Jesus said 'anyone who is so much as angry with a brother or sister is guilty of murder. Carelessly call a brother 'idiot!' and you just might find yourself hauled into court.'

Grudges towards coworkers, family and friends can be subtle and invisible but no less real and consequential as visible damage. When Garfunkel asked Simon recently why they hadn't seen each other, 'Paul mentioned an old interview where I said some stuff. I cried when he told me how much I had hurt him. Looking back, I guess I wanted to shake up the nice guy image of Simon & Garfunkel. Y'know what? I was a fool!'

The sense of freedom, joy, yes tears, and the possibility of singing together again has only been possible by them talking it through.

Forgiveness won't necessarily mean condoning or reconciling, particularly if a crow has swooped on you. And sometimes those opportunities will be out of our reach. But however out of control our grudges may feel, we can hand them over, in all their deathly ugliness, to someone who is willing to absorb them.