The election of a new government in the United Kingdom has felt like an opportunity to fix some of the daily challenges faced by the people of these isles. As a member of the Conservative Party, it also presents the chance for those of us who are Conservatives to take stock of what it means to be conservative and how best that definition can serve the people of the UK in a way that benefits the whole and not just specific parts.

Those who follow the internal machinations of the Conservative Party will know that the battle for a new leader has already begun. For the most part, it has focused on whether the Party needs to move to the right to combat the offering by the new kids on the block – Reform, or to the centre in order to block the leaking Shire vote that shifted to the Liberal Democrats. I want to propose a different approach.

For years as I was growing up, probably influenced by the media and how it presents politics, I assumed that the idea of a minimum wage was a socialist idea or what we might today describe as progressive politics. Things changed, when I studied the history and influence of Christian thought on Western economics, as part of a Masters in Biblical Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

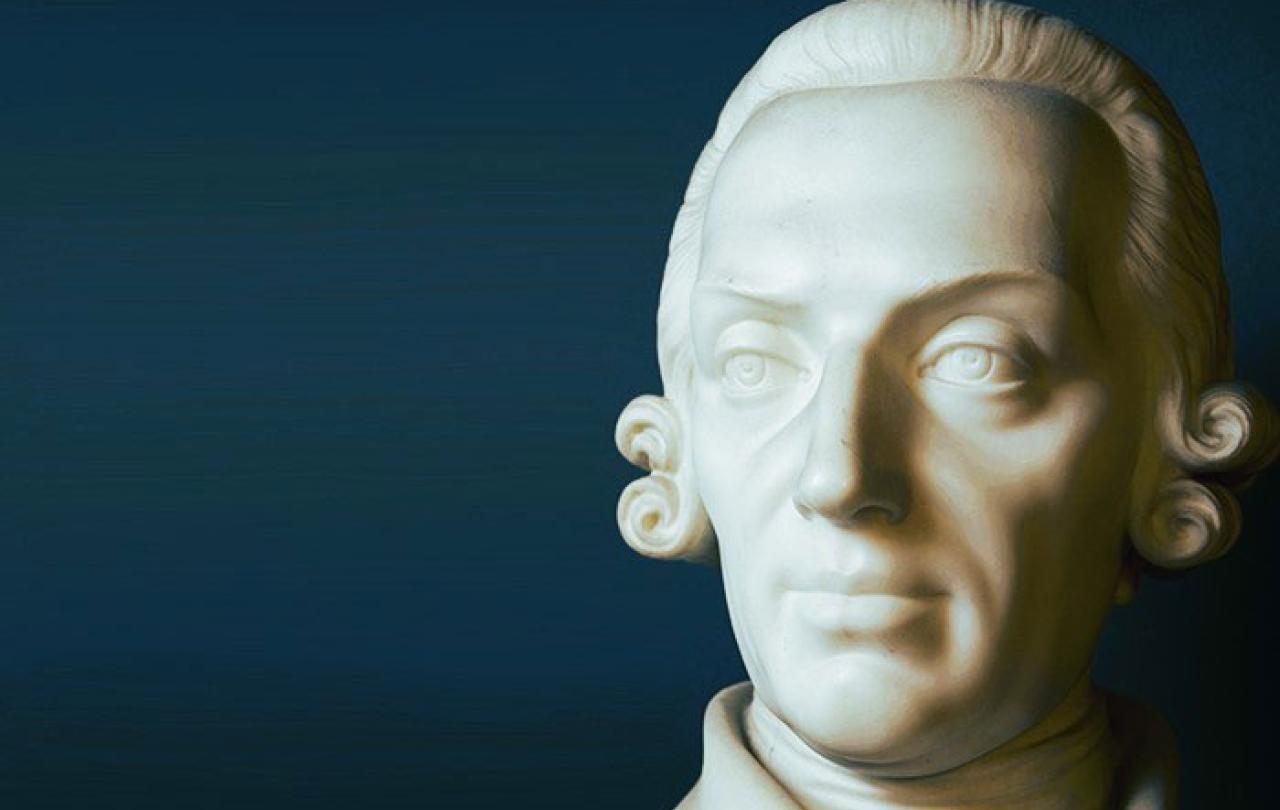

Adam Smith is the father of modern capitalism and hero to many conservatives. His foundational text, The Wealth of Nations, was on the reading list. Prior to these studies, I had heard and seen many conservative commentators use that text to support their claims around small government. I had also seen liberal commentators vilify his work for being the source of our broken Western systems. Many claimed that it was the basis for the economic thought and principles of Hayek and Friedman, the prominent economists who influenced the policies of the Thatcher government in the UK and the Reagan government in the US.

It tells us that our dogmatic positions should not prevent us from focusing on what is in the best interest of the people that politics and economics are supposed to serve.

When I read The Wealth of Nations for myself, I was shocked. I couldn’t believe how much of what he had actually said was ignored or had been misrepresented. Reading it for myself changed my assumptions and my learned narrative on capitalism. One of my greatest surprises was that Smith held what I had known to be a socialist policy, the idea of a minimum wage. To him it was such a fundamental truth that it was only briefly mentioned. Perhaps, that’s the reason so many people miss it.

Another shock was discovering that Adam Smith wrote about the place of government in regulating large corporations. For Smith, the wealth of large corporations was to be invested back into the areas from which the company was built. Jobs were to be kept local so that as many people as possible in society benefited from the wealth generated. Smith outlined that government regulation should prevent large corporations from moving their manufacturing operations to cheaper international locations to reduce costs and sidestep local communities.

Adam Smith, the father of capitalism – a protectionist and believer in the rights of workers! But what has this got to do with a discussion about the Conservative Party? It tells us that policies that do not always favour corporations but help workers or local communities are not unnecessarily anti-capitalist and by extension unconservative. It also tells us that our dogmatic positions should not prevent us from focusing on what is in the best interest of the people that politics and economics are supposed to serve.

My party needs to move away from policies that are focused on ideological battles and economics rooted in abstract ideals. And, instead, look to policies that will tangibly help everyday people. Or put differently, the party needs to move away from Oxford Union politics (I have nothing against the Union, I am a lifelong member!) and focus on real-world grown-up politics that improve the lives of the ‘many not the few’!

Lord Cameron tried to move the party to a position often dubbed Compassionate Conservativism. In fact, the origins of capitalism have long been connected to moral principles. Adam Smith not only wrote The Wealth of Nations but also considered issues around morality in his The Theory of Moral Sentiments. For a government to govern effectively and an opposition to oppose properly, morality and the interests of the many must be reflected in policy. And in my humble opinion, it is not unconservative to do so.