Remember singing 'God Save the King' for the first time and it took a little more effort? Instinctively, we were so used the Queen, and unless you're well into your eighties the concept of a King will still be something a novelty. Slowly the stamps have changed, and new passports are finally being printed. After King Charles' first year on the throne, and having celebrated his 75th birthday this month, we can reflect with a little more perspective about what it means to have a king.

A new king gives us an opportunity to look forward and back. The crown cradles continuity, bringing the past into the present. And whether you've been indulging in the latest series of Netflix's The Crown or venturing further back into royal history, we can also indulge in a little time travel. Maybe not a regal DeLorean, but if you hop inside the state coach there’s quite the ride to be taken. The historian Dominic Sandbrook recently detailed in The Times how in Britain that 'it is remarkable how often monarchs’ opening 12 months have set the tone for the rest of their reign.'

We find ourselves in a liminal space - not quite an airport terminal - but one where we are on our way although not there yet. We see glimpses of this still-coming kingdom, but not yet fully realised.

What if we went back to the future even further, considering Jesus Christ as king? We might be unable to argue with the enduring legacy of this historical figure, but most of us are unfamiliar with Jesus as King. We tend to think of baby Jesus, Jesus feeding the five thousand or Jesus on the cross, but what about Jesus as King? Today the church celebrates the Feast of Christ the King, an interestingly fairly recent tradition. A bit like the John Lewis Christmas ad encouraging us to 'let your traditions grow'. But there is nothing new about Jesus' kingship. The church has always thought of Christ as King. According to the accounts of Jesus' life in the Bible, the topic Jesus taught on more than anything else was 'the Kingdom of God'. And King Charles’ coronation was itself a portal to the life of this king. The service began with the Chapel Royal chorister greeting the new monarch, ‘Your Majesty, as children of the Kingdom of God, we welcome you in the name of the King of Kings.’ His reply? ‘In his name, and after his example, I come not to be served, but to serve.’ It was a useful reminder that the form of servant leadership we have assumed and expected from the Queen and now the King is not a modern invention or interpretation of how monarchs should be.

Much like the arrival of a new king, Christ the King Sunday also enables us to both look back and look forward. We find ourselves in a liminal space - not quite an airport terminal - but one where we are on our way although not there yet. We see glimpses of this still-coming kingdom, but not yet fully realised. The word 'Gospel' was well-known in the ancient world, describing the good news of the rightful king who has returned home to take this throne.

But this king is quite the contrast to the strong leader we're used to. As we look to world leaders today, we see many elder statesmen (you decide whether 'elder' or 'statesmen' should be emphasised!). There are different understandings and projections of what strong leadership looks like.

The historical reality of Jesus, his fingerprints on the world today, and the professed experience of millions of people worldwide continue to subvert.

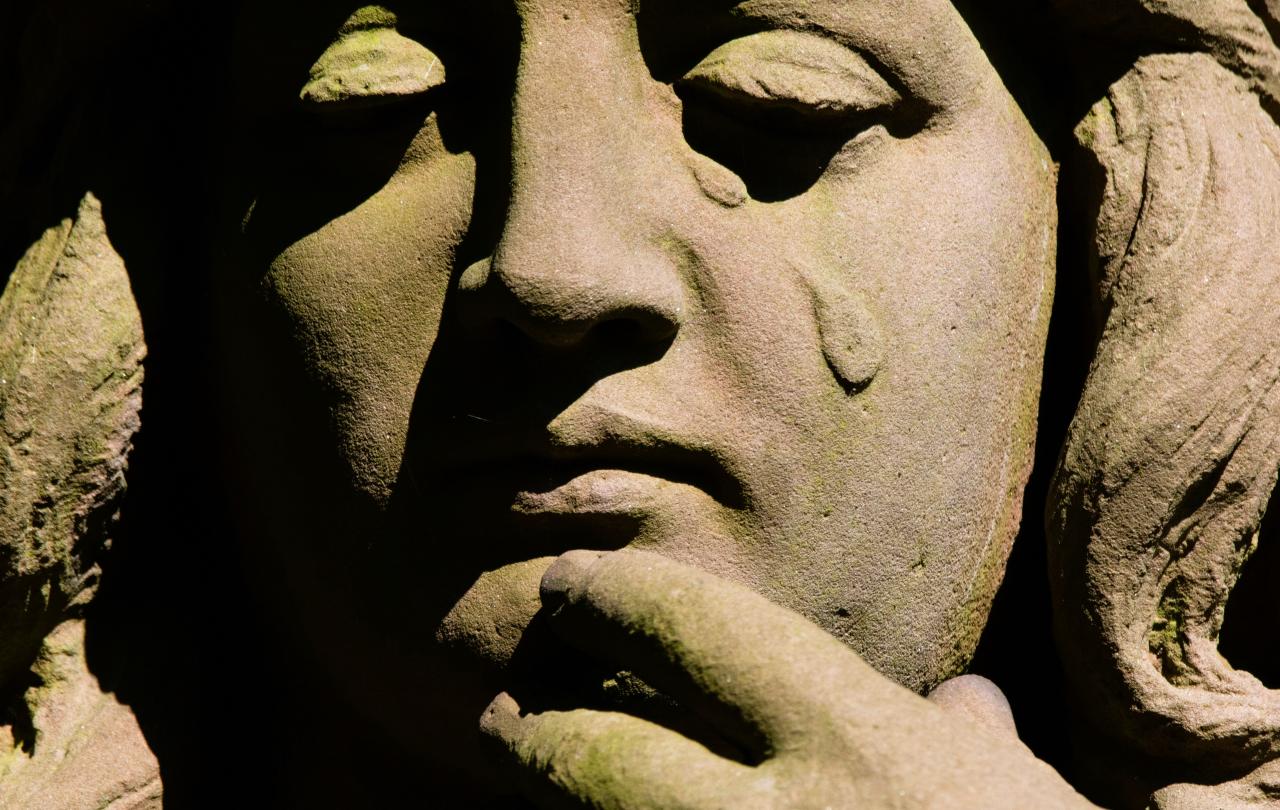

Jesus is a king who comes in humility. There was speculation of a slimmed-down coronation for King Charles proportionate to the cost-of-living crisis. But in Jesus’ mind must have been more the cost of dying, as he rode on a donkey into Jerusalem, surrounded by a fickle crowd cheering his own coronation before condemnation only a week later. At his execution there was mockery with the sign on his cross ‘King of the Jews’, and of course wearing a crown of thorns. If you travel back to his birth, the magi bring royal gifts, so his life is bookended with rumours of kingship.

What might this mean for us in the twenty-first century? On the one hand, there’s the personal, individual connection to the king. Pope Francis heralds ‘Christ the King who conquers us’. We’re happy for his rule and reign out there, but what about extending into our own lives? For the past few years on the eve of Christ the King I've been to baptism services at Southwark Cathedral. One of the symbols of the water in baptism is that we overwhelm our lives with Christ's life, and ultimately his reign over who we are, how we are, and what we do. Then there’s the broader reality: a king who does not neatly or easily fit into our political paradigms, whose priorities in one way or another will catch us off guard.

Jesus is the king who turns things upside-down. His kingdom is not marked by borders but is still whispered of and spoken about two thousand years later. That is what we sing about at Christmas. The king arriving in vulnerability as a baby and one day - who knows when - Christians believe he returns in power as king. On that day, Christians believe justice, goodness and all that we long for will be ushered in. But until then, the historical reality of Jesus, his fingerprints on the world today, and the professed experience of millions of people worldwide continue to subvert.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian famous for plotting to kill Hitler said, ‘A king who dies on the cross must be the king of a rather strange kingdom.’ The mystery amidst the majesty. Keep looking back. Keep looking forward.