I have been a David Baddiel admirer ever since he penned the anthem Three Lions with his friend Frank Skinner. The song has provided a hymn of hope to every England fan since 1996. “Football’s coming home”, I sing to my friends, family and TV screen every time England plays. Fans declare it out over the pitch, as though the louder they sing, the more likely it is their prophecy will come true.

As the author of a song that has sought to inspire faith in the England team it is perhaps ironic that David Baddiel’s new book “The God Desire” is all about why he cannot bring himself to have faith in God.

I really enjoyed reading the book and the subsequent back and forth I had on Twitter with Baddiel. He comes across like the kind of guy it would be great to sit in a pub with and talk about life, faith and football until closing time. I hope I get the chance.

The book, for me, offers three significant strengths and one major topic of contention.

A new tone for the new atheists

Baddiel offers what might be called a ‘New New Atheist’ approach. He differentiates himself from the now old New Atheists like Professor Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennet, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchings by challenging their machismo:

“Some atheists divine [sic] – correctly – that what religion provides for human beings is comfort, and then, in a way that can feel a bit adolescent, they feel impelled to say, essentially, ‘Comfort? That’s for babies.’ “

Baddiel refuses to ridicule the consolation of faith and indeed seems instead to long for it. He is kinder, warmer, more polite than old New Atheists, taking a far less dismissive tone. Perhaps part of this comes from his deep and sincere friendship with Frank Skinner who is a devout Catholic Christian. Their friendship is reflected in Baddiel’s robust yet gracious approach to controversial topics. It is an approach that can act as a model for a lot of our discussions in increasingly polarised times.

Baddiel’s critique of New Atheism also has an epistemological angle. He observes that in an age of social media our relationship to the concept of truth has changed. He reflects that in previous eras truths were handed down from authority figures but now there is a democratisation of truth - through social media everyone can share their own truth.

This is one of Baddiel’s most interesting observations:

“In a moral universe dictated by social media, punching up and punching down are the new markers of good and evil, and if religion is no longer considered a vastly powerful and high-status force, but rather a series of fragile and individual identity-based beliefs that only the unkind would mock, then atheists become pariahs.”

I think Baddiel might be on to something important here. For some atheists, religion is still a huge and influential behemoth that needs to be taken down. We can see that in the aggressive antireligious tweeting of Professor Alice Roberts or the theologically ill-informed op eds of Matthew Parris. They “punch up” against the authority of religion. Others “punch down”: from their morally superior position they are prepared to issue something akin to imperialistic judgmentalism against anyone who dares to identify as religious.

But punching up or punching down says nothing about the truth or otherwise of the position. Instead, it speaks to relative social position. Like Baddiel I believe both in the right to freedom of expression, and in the concept of objective truth.

An honest recognition of the desire for God

This new tone permits Baddiel to admit that he recognises in himself the existential longing for the things that faith can provide. He writes:

“My argument, on the other hand, is, in a general sense, psychological. It requires an admission, which frankly most atheists, I’ve noticed, aren’t prepared to make. Which is: I love God.”

Baddiel’s coming out with this brave admission reminds me of these words of Canadian artist and novelist Douglas Coupland as he draws to a close his book “Life After God”:

“My secret is that I need God—that I am sick and can no longer make it alone. I need God to help me give, because I no longer seem to be capable of giving; to help me be kind, as I no longer seem capable of kindness; to help me love, as I seem beyond being able to love.”

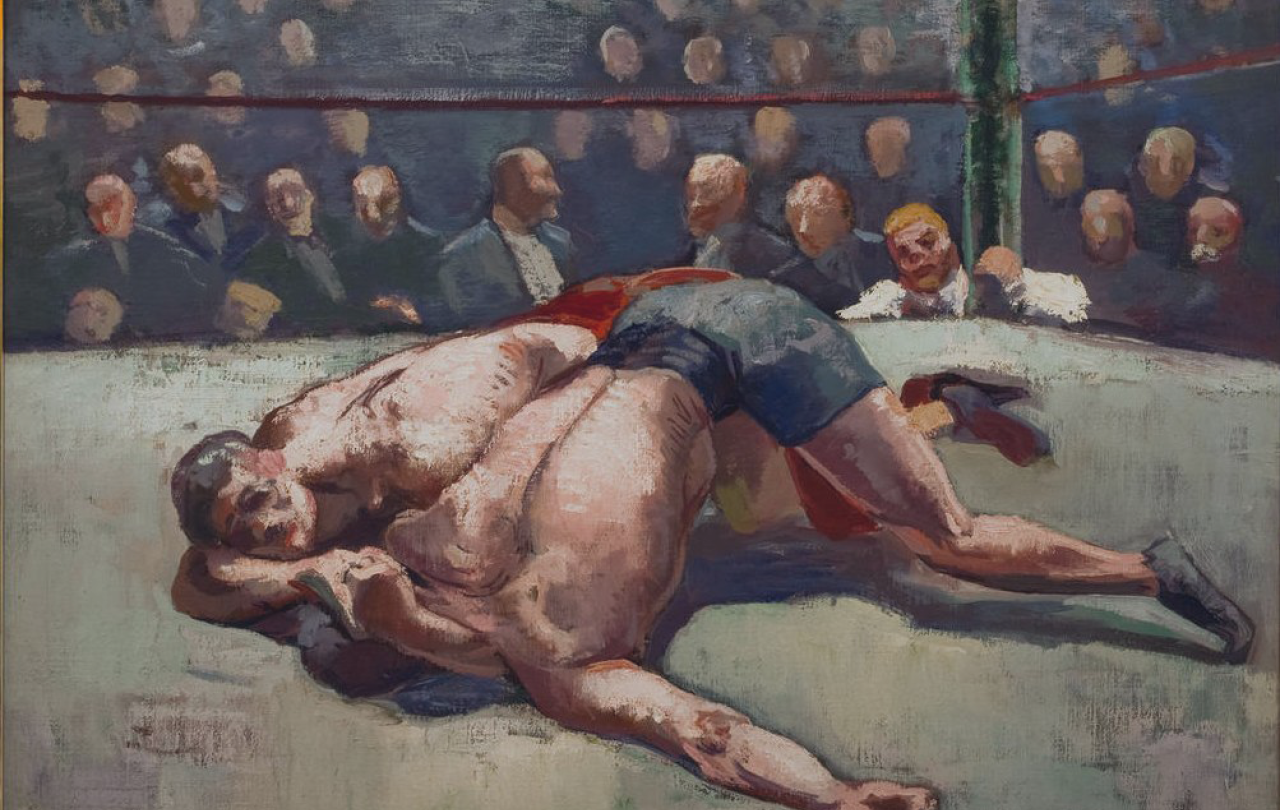

Some might read too much into Baddiel’s confession. A whole book explaining why he doesn’t believe in God may seem then pointless, as though he “doth protest too much.” But for me Baddiel’s short book still feels important – it represents an internal wrestling match that many people can relate to – wanting to believe in God on one hand but struggling to find the evidence on the other.

A helpful evaluation of the benefits of faith

Baddiel explores three reasons why he would love to believe in God: story, parenthood and immortality.

Firstly, he recognises a longing for meaning in life. He believes that belief in God can provide the possibility of life having an external story, offering not only direction and significance but a source for moral evaluation:

“God also offers story. Humans have a need to organise, to structure, the chaos of existence. They need to feel that life has narrative. Narrative requires satisfactory checks and balances, such as good being rewarded, and evil being punished. God provides all this. He storifies life… With story comes another God benefit: meaning. A sense, on an individual level, that your own narrative has significance: that it matters, in some way. This can only be the case if Someone or Something is taking account of it.”

Second, Baddiel notes that God provides an answer to the longing for there to be a benevolent force guiding us through the universe. Baddiel frames that in the need for a parent-figure:

“God is this: an archetype, a super-projection, of a parent who can be both blissful and terrifying.”

This could be seen as a recycling of the Freudian critique of belief in God as an immaturity, a babyishness as Baddiel might call it. But instead, it reads as longing.

Thirdly, and for Baddiel most significantly, God offers immortality. Baddiel puts it clearly:

“At heart, though, God is all about death. The other issues are spin-offs.”

Belief in God can help us confront the biggest fear that human beings face: the prospect of our own death.

A point of contention

As a Christian, there is much to agree with in the above points. However, my main point of contention is very neatly identified by Baddiel himself:

“The God Desire should not have to lead to the God Delusion.”

Baddiel seems to argue that the very fact that he wants God to exist must mean that he can’t possibly exist, that he must simply be a projection of his own desire. This is the exact opposite conclusion to that reached by CS Lewis following a not dissimilar journey to Baddiel’s:

"Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger: well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water… If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world…”

Baddiel concedes this line of reasoning but reflects that desire in those cases are met by tangible, visible things - food and water in this case. He summarises that “desire + invisibility = God.” God, for Baddiel, seems to be so utterly transcendent, that he cannot be evidenced, discovered, known. If he cannot be evidenced, then he cannot exist.

But what if God, truly and utterly transcendent, has chosen to make himself known? And what if that revelation is right under our noses in the person of Jesus Christ? This is the central and astonishing thesis of Christianity, grounded in the evidence of Jesus’ birth, his miracles, his teaching, and, ultimately, his resurrection from the dead. This evidence cannot be discovered merely by psychological reflection, as Baddiel has discovered. There are further historical, theological, spiritual, moral and scientific theories that need engaging with.

I hope that Baddiel writes a sequel. In it he would explain why his desire + invisibility equation does not stop him standing up for universal human rights, for example. He would investigate the historical evidence for Jesus and the concrete experiences of millions in their connection with God. He would look further at the explanatory power that the Christian faith gives to life and see why compassion and justice matter. He would admit that his sense of the divine, was evidence of God’s existence. He would discover that his love for God had been met by God’s love of him.

I am hoping one day there’s a warm fire, a cold beer and long night available to amicably talk these things through. In the meantime, I commend his book to you and encourage you, with Baddiel, to continue wrestling with the big questions of life.