If the 1980s were your formative years as a sports fan, you will carry many images with you even today. Dennis Taylor potting the last black after midnight to beat Steve Davis. Barry McGuigan defeating Eusebio Pedrosa in the ring at Loftus Road. The races between Coe and Ovett at the Moscow Olympics. The tie break between Borg and McEnroe. Botham’s Ashes. Diego Maradona versus England at the Mexico World Cup.

You will undoubtedly have other memories, though these will have been controlled by a limited number of broadcast editors. I clearly recall watching Viv Richards’ astonishing century in one cricket World Cup final against hosts England being regularly interrupted on BBC1’s Grandstand with coverage of a routine horse race meeting. The introduction of the less fusty World of Sport on ITV was a route in for some sports that faced an implicit class bias, but it was all still far removed from the 24/7 reverencing of sport today.

The eighties was an era of transition as sport began to gain a place in our cultural consciousness. It was also a decade in which the relationship between sport and politics became cemented on paths we still walk. In Everybody Wants To Rule The World, academic and journalist Roger Domeneghetti has written an entertaining and informative book subtitled ‘Britain, Sport and the 1980s’.

In our branding of the twenties as the decade of polarisation, we forget how deeply divided Britain was in the eighties. Recent commentary on the fortieth anniversary of the miners’ strike has been a reminder of this and how violent public life proved. Football hooliganism was pervasive and after a riot at a Luton Town – Millwall game in 1985, Margaret Thatcher asked of football officials: ‘what are you going to do about it?’. In a pithy and telling response, the FA secretary Ted Croker said: ‘Not our hooligans, Prime Minister, but yours. The product of your society’. Perhaps more than any other exchange, it symbolised the braiding of sport and politics, threads that endure to this day.

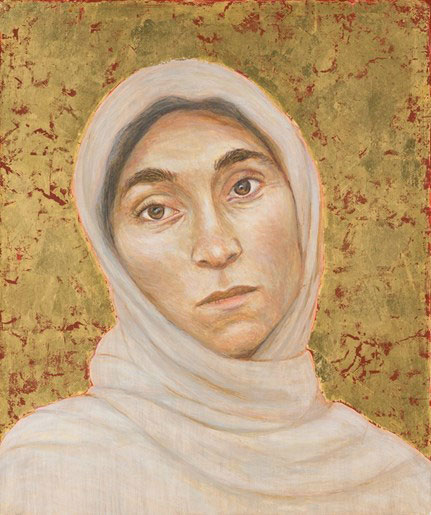

The sports stars of today have become surrogate saints, held up as an inspiration for what can be achieved and frequently employed as motivational speakers.

The argument that sport and politics don’t mix has a familiar ring for people who live with the tired old trope that religion and politics don’t either, as if our experience of culture and values are sealed off from each other. Sporting boycotts in the 1980s - from Olympics to apartheid South Africa – placed athletes in the unavoidable position of having to make decisions about participation that would reflect on their values and could affect their careers; positioning that other people were spared. These were an early taste of the moral standing afforded to sportsmen and women today; a status that somehow asks more of them, perhaps because other professions have become so tarnished and mistrusted.

Domeneghetti’s book is also a sobering reminder of how ugly and careless much of our shared life was in the eighties. The Bradford City fire and Hillsborough disaster were awful losses that showed the low priority of health and safety and the culture of institutional cover up that continues to blight the nation. The author locates these failings in the wider context of disasters like Kings Cross, Piper Alpha and the Marchioness boat as part of his bid to write a social history of sport.

Yet in a sense, Domeneghetti chose arbitrary parameters. Football in particular was on the cusp of a revolution with the introduction of the Premier League in 1992. Cultural sympathy for the game was about to change with the writings of Nick Hornby in Fever Pitch and Pete Davies in All Played Out. The nasty face of football was to be transformed into a highly marketable model.

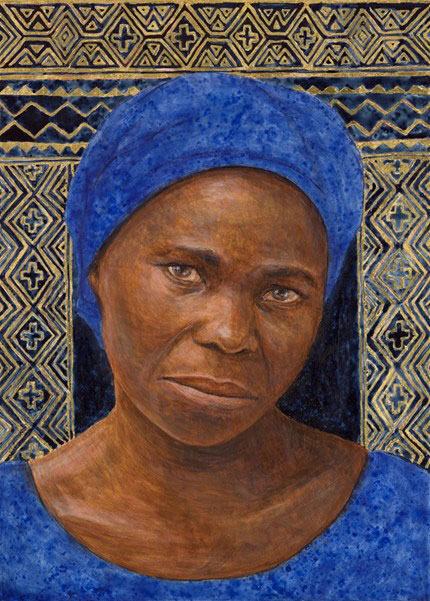

The ugliness of the era is laid bare in the prolific and casual racism, sexism and homophobia that coursed through every sport. The Windrush’s second generation broke through in the 1980s, notably in football, but was met with staggering levels of prejudice. Anyone tempted to think this has now been eradicated hasn’t spent any real time at a football ground or on social media. Women’s sport had virtually no profile in the eighties outside of tennis and athletics and as recently as 1978, Lord Denning had ruled that an eleven-year-old girl should not be allowed to play competitive football against boys the same age even though she merited a place in her team. Meanwhile, stars like Justin Fashanu, Martina Navratilova and John Curry were targeted for their sexual orientation. It remains hard for present day athletes to identify as gay, despite the rhetoric of acceptance. Sport then, as now, held up an unerring mirror to our faces.

The sports stars of today have become surrogate saints, held up as an inspiration for what can be achieved and frequently employed as motivational speakers. But there is the gloss of a hyper-individualistic, neo-liberal culture. Sports stars succeed because of a combination of innate gifting (which cannot simply be replicated) and material advantage (too many Olympic medals are still awarded to wealthy and advantaged Britons). I won because I wanted it more is a dishonest assessment of sporting success in the UK and in this way also holds up a mirror to other walks of life.

The powerful personal branding of today’s athletes in many ways have their origin in the 1980s and the way the likes of Ian Botham, Carl Lewis and John McEnroe transcended their sports. The cult of the conquering superstar is a smart diversion from the reality that money usually wins. Just look at the Premier League table.