The victims of envy

One of my favourite exercises to facilitate with large groups of people is called, ‘You at Your Best’. I introduce them to a list of positive qualities of character (wisdom, gratitude, kindness, self-control, bravery etc.) and then get them to pair up with someone they have never met. They tell a story of them at their best. When, in the past week, have they behaved in a way that was admirable? When did they surprise themselves with presence of mind or wisdom in action? It is a short exercise. It only takes six minutes. They tell the story, and the other person spots the strengths of character they hear in it.

Most of the stories aren’t that exceptional – a problem solved at work, a small kindness shown to family, an awkward but necessary moment of truth – but invariably the room becomes deafeningly voluble as people share their finest moments with a receptive audience. It is amazing how energised people become when given permission to talk about living close to their ideals. Within minutes people who had previously never met are gabbling away to each other like long lost relatives. Strangers have become friends. Outsiders feel included. No one wants to stop.

The hardest part of the exercise was to admit to a time when they were strong, kind, wise, brave, or honest.

When I finally manage to reign in the raucous joy of connecting people, I’m curious to know how they found the exercise. Almost always someone will say that they found it unnerving to talk positively about themselves. The hardest part of the exercise was to admit to a time when they were strong, kind, wise, brave, or honest. They noticed a kind of internal barrier to their willingness to voice their own virtues. It feels socially dangerous or ethically wrong to say good things about themselves out loud. Their social conditioning tells them that bad things will happen to them if they do.

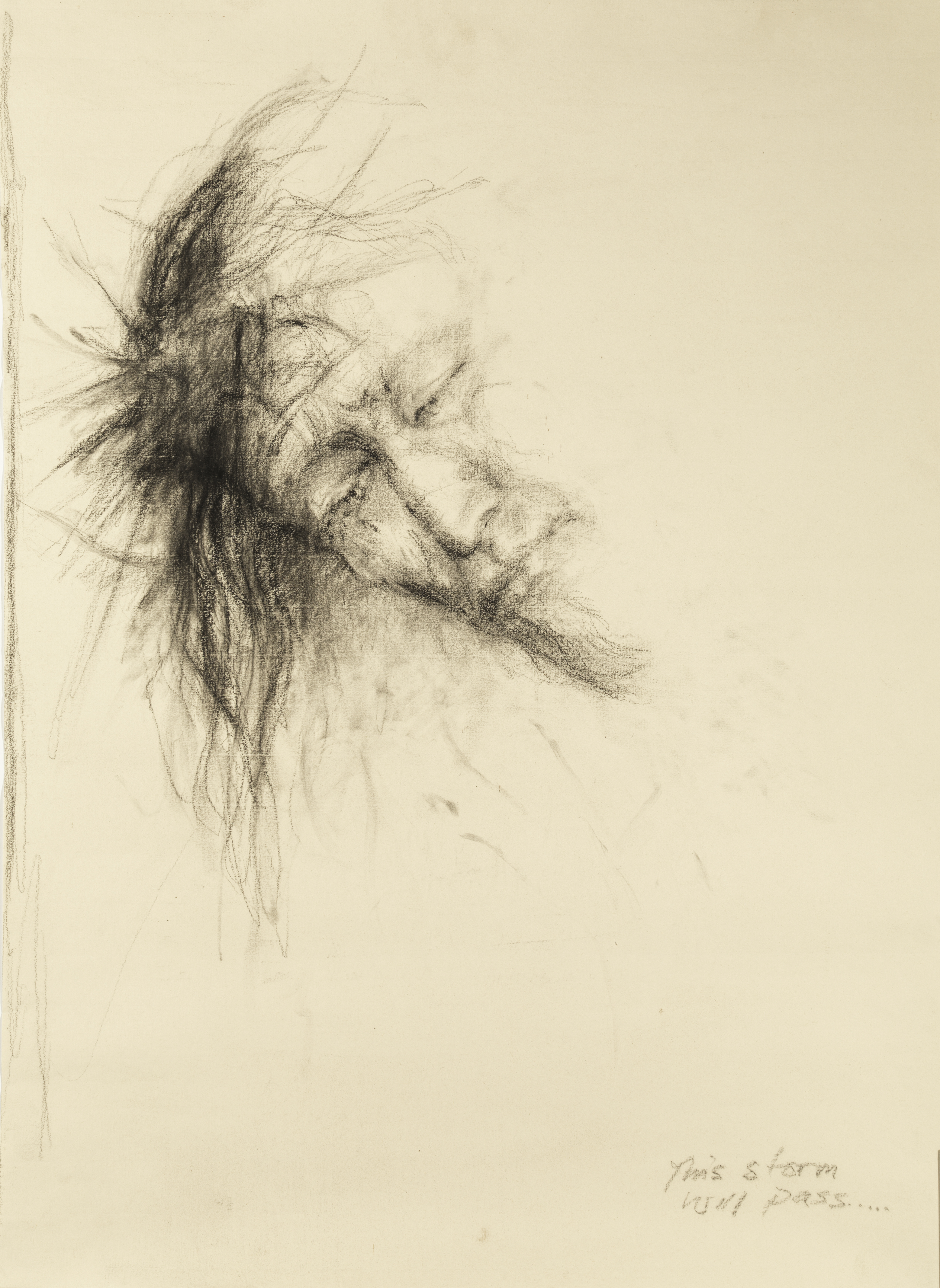

When someone voices a sentiment like this – a nervousness to acknowledge the goodness they contribute to the world – it is not an expression of humility or modesty. More likely, at some point, perhaps for a prolonged period time, the very things that are best and most beautiful about them, have been attacked and criticised. I’m pretty sure I’m dealing with a victim of envy.

The misdirection of envy

Envy is greatly misunderstood in our time. It was once named among the seven deadly sins. Deadly because, when unchecked, it has the capacity to possess a human being entirely, to become their modus operandi, to subtly pollute every thread of relationship with which they have contact. Sin because… well, as a way of being, it poisons any prospect of joyful human community for those who are beholden to it.

To make matters worse, we are often unclear about the terminology, particularly the difference between jealousy and envy. But the distinction is crucial. To be jealous is to protect and defend what is ours. Most obviously demonstrated in sexual or romantic relationships, jealousy is the instinct to protect the boundaries of a precious relationship, to view anything that threatens our commitment to those we love, as a temptation to be resisted. Sure, it can be over-played, it can become possessive or confining, but if our partner never shows jealousy, never expresses frustration at the things that spoil or reduce the quality of our shared intimacy, we are likely to wonder if they care at all. Advocates of the sexual revolution have been predicting the demise of sexual jealousy since the 1960s. They view it as a holdover from our evolutionary origins, no longer necessary in the contemporary world, past its sell-by-date and soon to be dispensed in the era of free-love. But rumours of the death of sexual jealousy have been greatly exaggerated. Our hardwired instinct to hang onto love still hangs on. Most of us feel that a relationship entirely stripped of jealousy is a relationship stripped of love.

Envy sees the strength, talent, or goodness of others as a threat and, if we can’t own them, vows to destroy them.

The psychological contours of envy are similar, but darkly different. If jealously wishes to cling to what is good; envy aims to destroy it. If to be jealous is to preserve what is ours; to be envious is to resent others for having what is theirs. Sometimes we don’t even want the things we envy, we just can’t bear the thought of someone else having them. Envy sees the strength, talent, or goodness of others as a threat and, if we can’t own them, vows to destroy them. It is the message behind every honour killing, the mantra of every domestic abuser: if I can’t have you, nobody can. It is the ethos of the competitive workplace in which others’ success is our failure - with every colleague who succeeds something inside of us dies.

But this isn’t how envy is usually portrayed. Looking at the pop-culture definitions of envy that surround us, we could be forgiven for thinking envy is a bit of a laugh. Harmless, desirable, even good. Hardly a deadly sin, nowhere near the toxic desire to destroy the unique beauty of the other, more like the branding of our favourite nail salon, or eau de perfume. We are immersed in propaganda for envy-lite: the cheeky and indulgent desire to make other people wish they were us.

But perhaps the main reason envy is so bad, the reason it consistently ends up on these ancient lists of how not to be, is that it has no end game.

There can only be ONE

We are subject to a misdirection. As every totalitarian propagandist knows, the best way to make people malleable is not to present them with a clear thesis with which they can argue, but to drown them in so much inconsequential information, so much white noise, that they can no longer discern what really deserves their attention. We are made to look in the wrong direction. Spotting the minor envies but completely oblivious to the major envies that act as invisible killers in our social water supply. We spot the envies we can laugh at while passing by the envies that leak into everyday life undetected, like carbon monoxide. We strain out the gnats but swallow the camel.

Envy in its most deadly form is often too familiar to be noticed. Ever since Cain killed Abel, the most damaging expressions of envy have been found in families. Siblings compete against one another for the limited resource of parental affection and devise a surprisingly innovative set of chess moves designed to gain approval. Some families resort to an ever-shifting set of alliances and betrayals, like a royal court, a game of musical chairs in which the aim is not to land in the blame seat when the music stops. Other families, especially larger families, resolve the issue by carving out unique turf for each child. We recognise these stereotypes: the cool one, the funny one, the clever one, the spiritual one, the naughty one. The Spice Girls were not the first to realise that a one-word identity can help us stand out from the crowd. It works fine, until we run into someone else who has aligned themselves with the same brand.

Sit-coms are filled with the comedic fallout that occurs when people meet their doppelganger in the workplace. There can be only One - one boss, one comedian, one intellectual, one golden boy, one damsel in distress- and envious war engulfs the boardrooms, staffrooms, and multistorey carparks in which Two meet. If we ever notice the green-eyed monster arising within us, we would do well to ask ourselves: what is the turf I thought was mine that this person is trespassing upon? If we can detach ourselves from the desire to destroy our competitor, and reflect on that question, we’ll come to realise that we were always much more than the fistful of traits that defined us in our family.

No end game

But perhaps the main reason envy is so bad, the reason it consistently ends up on these ancient lists of how not to be, is that it has no end game. There is no better future into which envy would deliver us, it simply aims to negate or nullify whatever threatens our ego at any given moment. If only X were not like that, goes the logic of envy, then everything would be okay. But envy is a myopic state, it can see no further than the restoration of a self-centred status quo. It contributes nothing to the thriving life of joy and love usually associated with the de-centring of the self.

The comparison with jealousy is again illustrative. Ultimately, a jealous act – in friendship or marriage or the workplace – when performed skilfully, is an act of hope. It values what is and holds the belief that the world will be better for everyone if the goodness we know now can be nurtured and preserved into the future. It requires not just an opposition to that which would spoil what is good, but gratitude for the good we already have. Jealousy enjoys, appreciates, and savours the beauty that is already present and aspires to magnify its legacy. Envy despises what is and can conceive no other response than burning it to the ground.

The celebration of envy when taken to its logical conclusion, is the pursuit of a fiction, an impossible fantasy that can never be realised. It invites us to imagine nullifying the strength of all others, so the entire world revolves around us, the only star before an obsequious audience, coerced into adoration. Envy partakes of a cynical philosophy of non-existence, and this is what make it a deadly sin. Not that it is naughty but fun, but that it is pointless and empty.