Bach’s theological credentials are impeccable, as Jeremy Begbie wrote about previously for Seen & Unseen. But Beethoven’s? Not really. In fact, not at all. Most scholars on Beethoven see him as a secularizing force. If Bach represent the summit of theological expression in western music history, then Beethoven is the poster boy of the Enlightenment progress. He spells the end of sacred music. In the narrative of music history, Beethoven is the catalyst for a new secular epoch. After Beethoven, music is no longer about God but humanity; sacred music drops out from the historical narrative as something irrelevant or even regressive to the progress of modernity.

But it is not just any Beethoven who wields this secularising power. It is a very particular Beethoven, more myth than man. This is Beethoven as Promethean hero. He overcomes his deafness by defiance, grabbing fate by the throat as it knocks loudly in the opening bars of the Fifth symphony - da-da-da-daaaa! - and triumphing over its C-minor threat in a glorious blaze of C major in the finale. The symphony is a musical model of human self-determination. It projects Beethoven as a revolutionary artist living in revolutionary times, channelling the anticlerical and antimonarchist fervour of the French Revolution in musical form. His story is one of freedom and autonomy; and his music is made in his image, free from servitude to church and court, and free to be itself.

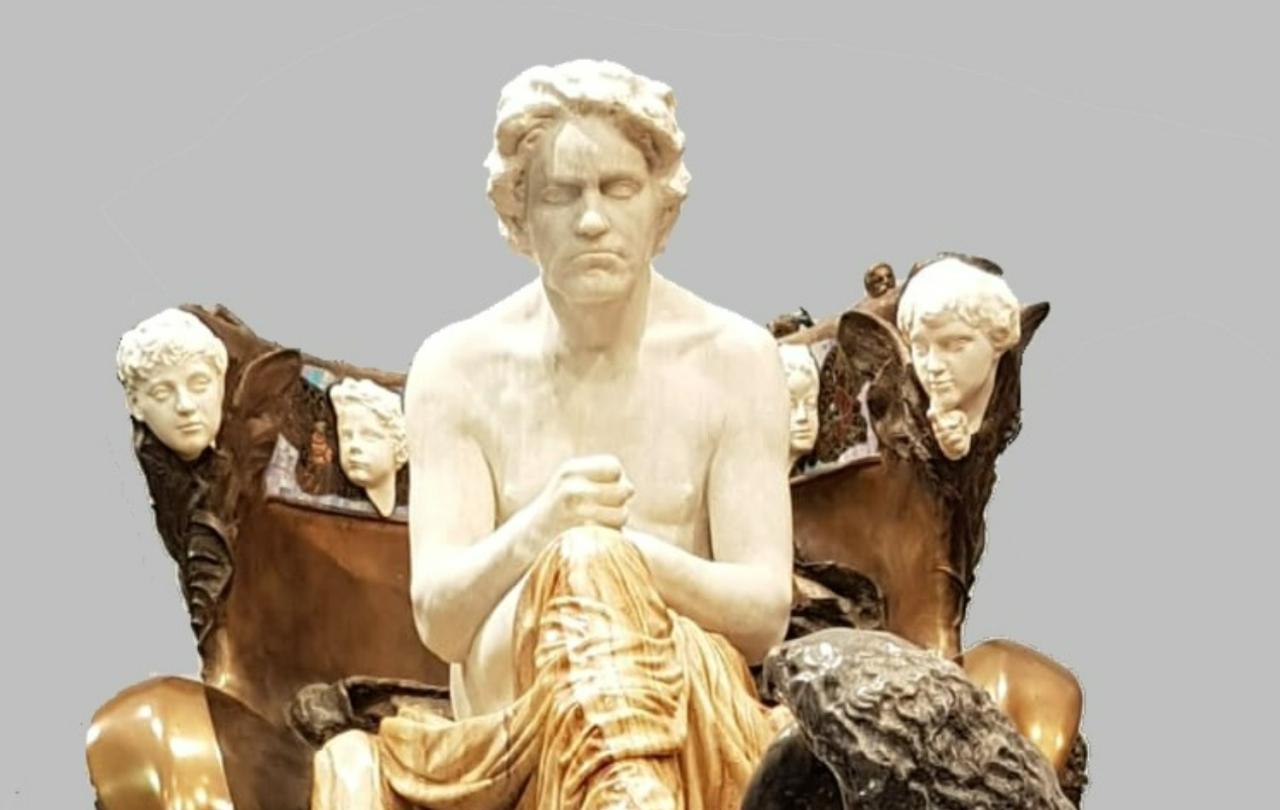

This Promethean image precludes Beethoven from being a sacred composer. It is not that he isn’t a sacred composer; rather, he can’t be one in this historical narrative. In fact, Beethoven stands as a rival to the sacred, because by the beginning of the 20th Century, artists such as Max Klinger were building shrines to the composer: Beethoven is the high priest of an art religion.

The Beethoven monument

The Vienna Secession’s fourteenth exhibition in 1902 was a shrine dedicated to Beethoven with Max Klinger ‘s monument as the altar.

But there is a problem. Beethoven wrote sacred music. Not much, admittedly, but enough, including what he declared to be his ‘greatest work’ – the Missa Solemnis. So in order to uphold a more secular Beethoven, scholars have had to explain away his sacred music as inconsequential and his religious beliefs as unorthodox or non-existent. They tie themselves up in knots trying to solve the problem, especially with regard to Beethoven’s magnum opus. Although there is nothing theologically unorthodox in the Missa Solemnis, somehow the mass has to be theologically unorthodox for these commentators: at best it is a mass for deist, but it is mostly a mass about humanity. The liturgical bits can be dismissed, they claim, as something that stifles what is truly Beethovenian; instead, to grasp its meaning, you have to listen to the mass as if it where a symphony resonant with tones of human freedom and autonomy. It is almost as if Beethoven wrote the mass against his will. In one recent biography, the chapter on the Missa Solemnis opens with the incredulous question: “Why did Beethoven write a mass?”

Why not? The problem is not Beethoven’s (obviously) but the biographer’s belief in a history that sits uncomfortably with the composer. Yes, Beethoven was a revolutionary in the times of revolution. Yes, he was born in the Age of Enlightenment, and even declared ‘freedom and progress’ as the main purpose of art. But that does not make him French; he did not step foot in France, and despite the Napoleonic aftermath of the French Revolution, what Enlightenment meant in Bonn where Beethoven was born and in Vienna where he died, could not be anticlerical or antimonarchist because these cities were under the rule of Enlightened despots who by definition had both kingly and ecclesiastic functions. In other words, Beethoven was a child of a religious Enlightenment. This means that his innovative and radical works were not composed against the sacred but were inspired by it. This is not to say that there is no truth in a Promethean view of Beethoven or that there is no conflict in his music during this tumultuous period in Europe, but it does imply that Beethoven upheld sacred music. In fact, he leads it in a new direction. And, if we have ears to hear, then the Missa Solemnis can open up a new sound world full of theological resonance.

While working on the Missa, Beethoven wrote out the Latin text of the mass on a piece of paper and added a German translation next to each line. As a teenager, Beethoven regularly played the organ for mass in the court at Bonn; he knew the Catholic liturgy from memory. So why would he write out the text and its translation? Because he wanted to explore the meaning of each word more fully, looking up a German dictionary for definitions and synonyms that would enlarge his understanding of the text. And if the expression mark in the score of the Missa (‘with devotion’) and his collection of devotional literature in his library is anything to go by, this process was an act of meditation for the composer. This was no routine setting of the mass. In fact, if you listen carefully, not only did Beethoven look up individual words to amplify their meaning, it seems that he also looked up the biblical reference to set their meaning in context.

Listen to the Sanctus: you will hear echoes of the biblical book of Isaiah, chapter six. Beethoven conjures up a temple trembling at its foundations as the angels sing ‘Holy, holy, holy’. Similarly, in the Benedictus, you will hear echoes of the Palm Sunday procession from the gospels. The music is a match in the form of a pastoral; it depicts Jesus arriving as a king but in the form a humble shepherd riding a donkey, as the crowds chant “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.” There is no sense of Promethean triumph here, but the sound of meekness and majesty.

We don’t need to tie ourselves up in knots to understand Beethoven or the Missa solemnis as secular. May be, to use the composer’s own words, Beethoven was just an ordinary Catholic writing extraordinary music to ‘instil religious affections’ in the congregants. This view would be a more faithful account of the composer’s life, but it would also radically change the way we understand Beethoven and the subsequent ‘progress’ of music history in our textbooks. And this, perhaps, points to the most critical function of sacred music: to reveal the hearts of its hearers. The Missa solemnis, as Beethoven's greatest work, is a capstone which many have rejected as the cornerstone of his oeuvre. Try not to trip up on it.