‘Tis the season to be jolly and watching a good film with a cup of tea and a biscuit, while the freezing wind and rain whip at the window, can be one of the jolliest things you can do this year. The genre of ‘Christmas’ has only grown and grown over the decades, so if you’re stumped by the myriad of choices – often dreadful schlock that feature the word ‘Prince’ and ‘Christmas’ in the title superimposed over a picture of two ludicrously attractive people staring lovingly into each other’s eyes in a blizzard – take comfort in my Top 5 Christmas films.

Note – this is my top 5. My personal top 5. These are not the ‘best’ Christmas films. You will not find It’s a Wonderful Life on here. It is glorious and lovely, but I saw it too late in life, and just don’t emotionally resonate with it as much as other Christmas films. I will not apologise. You will not see Die Hard. It is indeed and iconic action film, with a superb Alan Rickman performance, and it is indeed set at a Christmas party…but that isn’t enough to make it a ‘Christmas film’. I WILL NOT APOLOGISE!

5. The Nightmare Before Christmas

I would have put this film higher up the list if not for the fact that it straddles two seasons – All Hollows and Christmas. This film is iconic, however. The stop-motion animation gives the whole affair an extra haunting air. The music is superb – I still find myself humming What’s This every few weeks. The story is unhinged (what else do you expect from Tim Burton?) but to just the right degree, and behind the ghoulish setting and mad-cap story there is a good old-fashioned moral-of-the-story for children and adults alike to enjoy. Nightmare is a marvellous reminder of what it means to have the Christmas spirit, and the great thing about it is that it’s a film you can enjoy any time from October 31st!

4. Bad Santa

Billy Bob Thornton is mesmerising as an ‘eating, drinking, sh***ing, f***ing Santa Claus’. This is not one for the kids! Thornton’s Willie T. Soke is a professional thief who, with his dwarf assistant, get jobs as a grotto Santa and Elf in shopping malls during the festive season so as to case the place and rob it…but this time is different. Soake’s degeneracy has become a serious liability, and his instability and vulgar sexual exploits catch the attention of John Ritter’s mall manager and Bernie Mac’s security chief. Soake is spiralling out of control, but perhaps a romantic relationship with Lauren Graham’s barmaid and a chance encounter with a vulnerable young boy (to whom Soake becomes the least appropriate father-figure) might just be his salvation, and teach him the spirit of Christmas. The script is jet-black funny, and all the performances are spot on – although this is entirely Thornton’s film to shine in. Lewd, rude, and crude, but with a heart of gold (deep down under all the effing and jeffing), this film is the perfect antidote for those who find the jollity of the festive season a little twee.

3. The Holiday

This film has Jude Law in it. This ought to be enough to commend it to you, but I’ll go further. This film has Jude Law playing a jumper-wearing widowed single-dad, who can turn the humble napkin into a delightful children’s entertainment, and who gives smouldering glances across a crowded pub. Before you all rush out to watch it, let me finish the blurb. Cameron Diaz and Kate Winslett are two women, unlucky in love, who decide to swap homes for the Christmas holiday. Winslett is escaping a toxic infatuation and finds solace in a friendship with a nonagenarian scriptwriter from the Golden Age of Hollywood, and a possible romance with Jack Black (giving a genuinely restrained and enjoyable performance). Workaholic Diaz is desperate to learn how to switch-off, relax, and maybe give love a chance. She finds solace in…Jude Law’s many lovely jumpers and smouldering glances. This is not a film to be described but experienced. Its camp and frothy and silly, but its also just really lovely and gets the tears going every time. If my recommendation isn’t enough, listen to my wife – watch this film over Christmas!

2. The Muppet Christmas Carol

It’s a well-known fact that you can’t improve upon the indominable prose of Charles Dickens…WRONG! Dickens made the fatal error of not putting Muppets into his story. Rizzo and Gonzo take on the role of narrators of the story, Kermit does a sparkling turn as Bob Cratchit, and Michael Cain stars as the best on screen iteration of Scrooge (go on, fight me on this!). It’s the well-worn story brought to life by glorious songs – every year I start to sing “Tis the season to be jolly and joyous” to myself – a side-splitting script, and a clear and tender reverence for the original story and its central message. I defy anyone, child or adult, to sit through to the end this wonderful film and not want to keep Christmas in their heart every day. If you don’t like this film then I can only guess that you’ll be visited by ‘Marley and Marley, WOOOOOOOOOOA’!

1. Love Actually

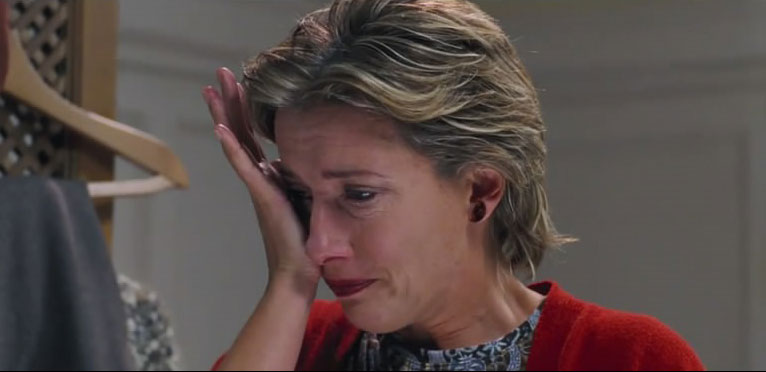

Richard Curtis is my favourite director. Every film of his, however flawed (and there a several flaws in Love Actually), is so warm-hearted and good-natured that I can’t help but love them. Love Actually is Curtis firing on all cylinder: a painfully funny script, an ensemble cast of Britain’s finest talent, and a score that plays your emotions like a fiddle. A series of interconnecting love stories – love found, love lost, unrequited love, misdirected love – playing out in the run-up to Christmas, this film will not fail to put a tear in your eye and smile on your face. At times it’s a little too ‘laddy’ – I’m looking at you American sexcapade storyline – and the fact that all these people live in gorgeous houses in Wandsworth in spite of doing no discernible work is infuriating, but the fact that it is number one on this list in spirt of this is mark of just how strong a film it is. The cast list alone puts it at the top: Hugh Grant, Colin Firth, Alan Rickman, Liam Neeson, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Bill Nighy, Rowan Atkinson popping in for a bit…EMMA THOMPSON! The raw power of Emma Thompson quietly weeping as she listens to Joni Mitchell and contemplates the implosion of her marriage is stunning to behold. At its heart, it is a simple Richard Curtis film; it wants the viewer to relax in the beautiful spectacle of love, and to know that they are loved. I love Love Actually, and Love Actually loves me.

EMMA THOMPSON!