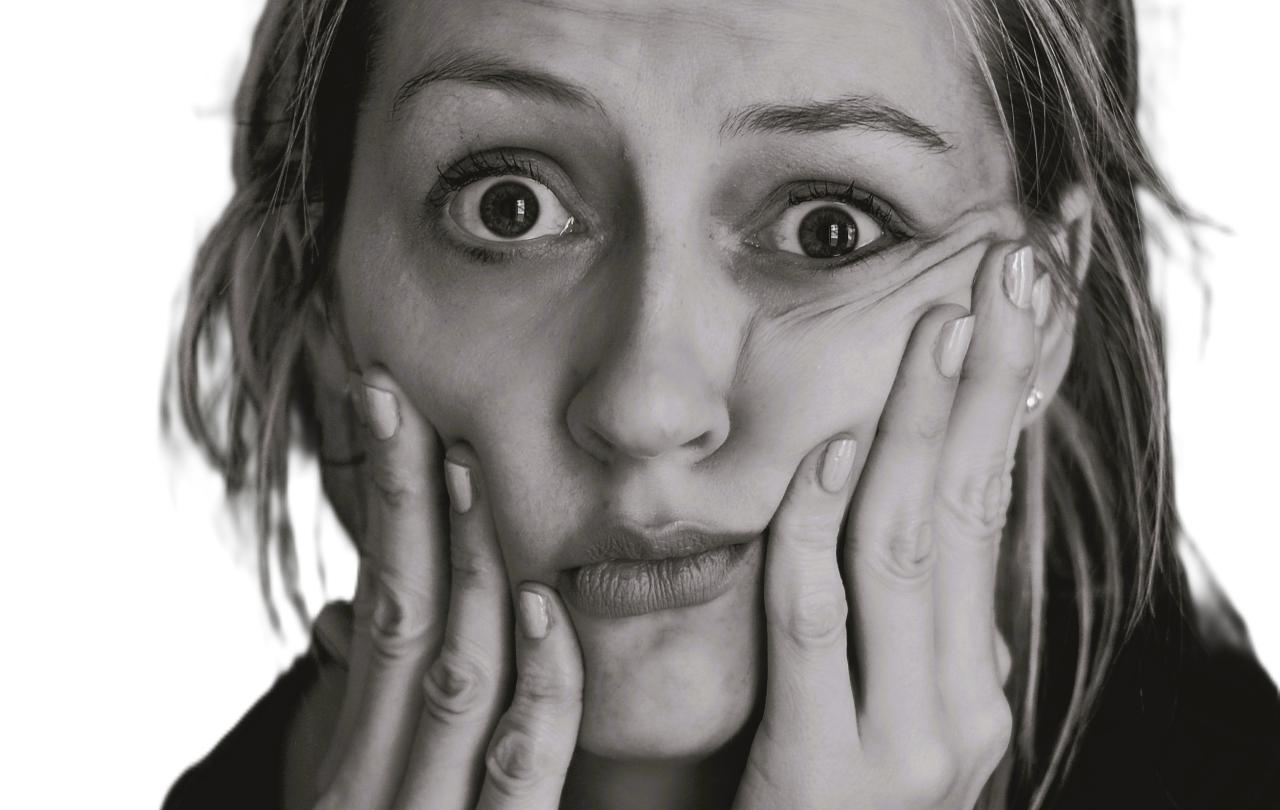

For the first few days of any summer holiday there seems to be something wrong with my brain. Having looked forward for months to the moment when I can finally down tools and get some rest, having yearned for weeks to be free of the relentless schedule of emails and meetings, the moment finally arrives and I, well… hate it. I’ve wanted to stop for ages and then when I get the chance, I don’t want to. The flywheel momentum of the to-do list somehow carries over into the holiday and turns the first few days into an obsessive nightmare of drivenness.

This usually manifests in the agitation of wanting to rest while being unable to do so. My schedule says stop but my mind hasn’t got the memo. Instead of gently sculling across the pool, I’m swimming time trials through an obstacle course of inflatable beds and dayglo sea creatures. My family is quick to remind me that the languid currents of the pool were designed for relaxation, not for achieving a personal best. ‘It’s called the lazy river, Dad, not Verstappen at the Nürburgring.’ It makes me laugh, but it doesn’t make me stop. Nor does it stop them shouting things like ‘He’s taking the apex’, and ‘Dad’s got DRS’ from their sun loungers every time I sluice past.

In the old days, psychiatrists used to call it the Sunday Neurosis, the mild state of agitated low mood that afflicted people on their day off. The inescapable feeling that we should be doing something on days when there is nothing to do. The realisation that we’re not quite sure who we are when we are freed from the daily demands we can easily resent. I don’t know what you have planned for the summer- a beach party in the Bahamas or an Airbnb in Bridlington or the classic post-Covid staycation- but if you’re planning to take a break of any kind there are a few things you should perhaps keep in mind to make the best of it.

If we must work full throttle to the final hour – we may have to accept that we’ll spend the first few days on holiday getting used to being on holiday.

First. Slow down slowly.

We have a tendency to think that life can change at the speed of thought. Just because our diaries say holiday, doesn’t mean that our bodies are working to the same schedule. The autonomic nervous system that governs our state of physiological arousal largely operates automatically. It isn’t synched to our Outlook calendar and can’t deliver relaxation on demand, no matter how much we would like it to. Psychotherapist Deb Dana likens changing our state of physiological arousal to taking a lift down a few floors. It takes time to move from a highly active state, to a more relaxed and connected way of being. It doesn’t happen at the flick of a switch and we only agitate ourselves more thinking it should. She says we should befriend our nervous system. Instead of impatiently asking ourselves why we aren’t more relaxed, we should simply ask whether we need to be this agitated right now. And if we don’t, accept that it may take us some time to adapt to a less demanding environment.

When it comes to holidays, this suggests we should allow ourselves some time to acclimatise. Our bodies don’t automatically relax the moment they hit the beach, or hike the mountains, or lie under canvas - they need some time. We can do this before the holiday starts, by slowly decelerating as time off approaches. Like a car approaching a junction, if we want to stop smoothly, we might want to hit the brakes long before we reach the stop sign. And if we can’t do that – if we must work full throttle to the final hour – we may have to accept that we’ll spend the first few days on holiday getting used to being on holiday. It may not make us a pleasure to be with, but we can at least understand that it’s just how our bodies work. We are not droids, there isn’t an off switch on the back of our heads.

On holiday, we can take time to savour the experience of living- to be in our bodies, not just use them.

Second, get into your body (and out of your mind).

There’s a reason people spend so much time on holiday exercising their bodies: surfing, climbing, walking, riding. And weird stuff too, that you’d never dream of doing at home. One time in Normandy we booked a hand-pumped locomotive and huffed/puffed our way up and down a railway line for an afternoon. If I didn’t have the blisters to prove it, I’d think I’d dreamed that. Why do we do these things? Because it feels good to be aware of our bodies. Even my laps around the lazy river had a certain logic to them.

Many of us spend most of our time in disembodied thought. We can sometimes feel like the involuntary participants in a workplace time and motion study, in which worth is measured by output. It doesn’t matter where you work – home, school, office, a boat, the woods – sooner or later a spreadsheet will find you. You can run, but you cannot hide your data. And the impact this has on us is that we tend to be more aware of whether we have hit our targets than we are of the toll these targets take on our bodily wellbeing. Just recently I was asked to support a management team going through a stressful restructuring. One guy claimed he didn’t feel the stress of it- he just got on with the job. But when I sympathetically suggested he might be paying for it with his body, the litany of physical ailments he produced sounded like the list of side effects in a 1980s pharmaceutical commercial. He didn’t think he was stressed, but his body kept the score.

Let’s face it, going on holiday itself is stressful. It’s ranked 42 on the Holmes-Rahe Life Stress Inventory, just above ‘minor violations of the law’. Apparently packing for Marbella is more stressful than being pulled over by the cops. But it’s worth it if it creates a space in which we can de-stress, a space in which we can remember that we have a body, a body that needs to be looked after. Of all the benefits of bodily awareness – the positive sense of how our body feels, not the crippling consciousness of how it looks – perhaps the greatest is its capacity to turn off the hyperactive judgement of our minds. On holiday, we can take time to savour the experience of living- to be in our bodies, not just use them.

If we are defined by our output, who do we become when our output drops to zero?

Third. Make time to connect.

What happens when we slow down and learn to live in our bodies again? We become open to connection: socially, emotionally, even spiritually. Back to Deb Dana. She notes that when we take that slow elevator down from the souped-up state of busyness to a more relaxed and open state of mind, we activate the ventral vagal nervous system. She calls it our ‘home away from home’- which seems especially apt for being on holiday. In this state we are happier to be seen by others and therefore to be in relationship with them. Whether it’s a conversation while walking, or an evening card-game, or a meal together, all of them offer a chance for us to dwell in our home away from home in connection with others.

One of the things that can keep us so obsessively busy, is that we are not always sure who we would be if we stopped. We’re not certain we have a right to exist when we’re not being productive. If we are defined by our output, who do we become when our output drops to zero? This is why for thousands of years the practice of rest has been enshrined in spiritual practices. Without space to detach ourselves from the hectic pace of life we will inevitably confuse who we are with what we do. The Judeo-Christian tradition called it sabbath, not just a day of rest, but a way of being in which there is nothing left to prove. Holidays can offer us that opportunity, if we are willing to take it. Because after all what do we call someone who becomes more relaxed and embodied and connected? I think: more human.