Last week my family laid my great-grandmother to rest. A few hours afterwards, we celebrated my cousin's birthday.

It felt strange to go from a place of death to a place of life in the space of a day. One minute I was throwing flowers into the open grave of a woman whose earthly life has come to an end and the next I was in a restaurant handing flowers to a girl whose life as a woman is just beginning. The contrast was a bit surreal, but much of life is like that; beginnings and endings flowing into each other. The transition between the two events was made easier by the fact that the funeral did not really feel like one. In alignment with my great-grandmother’s spiritual beliefs, the ceremony was very simple. It was over in less than four hours and featured a short reading of spiritual texts and quiet, reverent reflection. There were no solemn looks, no songs of lament, no dirt shoveling, no loud wailing or aunties and uncles dancing to Beres Hammond at the reception. Instead, there was just the quiet nod of acknowledgement that her spirit has journeyed on.

Though I missed the eulogies and shared tears that usually detail funeral services, I appreciated the simplicity of the ceremony. I appreciated the way death was described as a transition of the spirit into a new kind of life, the way it was treated as something so normal. Which in fact it is. Death is happening around us every day yet as a society it is something that we struggle with - whether it’s the death of a loved one, a career, a relationship or a part of ourselves. Our attempts to curate eternity with anti-aging procedures and technological permanence betray how deeply uncomfortable we are with the inevitability of endings in our modern world.

And to be honest, of course we are. The loss of loved ones shakes entire worlds. Job losses throw our lives into instability and leave us feeling unsafe. The loss of youth and power challenges long held ideas of identity and invites existential anguish. Divorce carries with it its own special grief. The pain of these experiences makes it hard for us to embrace when things are ending in our lives and make it hard for us to let go, even when we need to.

And we do often need to.

What fears, habits, thoughts or behaviours need to be given to the earth? What cycles or patterns do we need to bury and mourn so that we can usher in new and better ways of being?

Lately I’ve been thinking about the saying ‘your new life will cost you your old one’ and how true that is in many areas of our lives. In my own life, I recently started a new role at work that has cost me the comfort of my old one. I have had to give old versions of myself to the ground and shed skin so that I can continue to grow into the space of it. This new year of doctoral study has cost me Saturdays spent lazing around with friends, new relationships have cost me old patterns of behaviour and new depth in old relationships have cost me pride and ego.

At each point of transition, I have been asked to leave something behind to experience something new and it seems like so many of us at the moment are being asked to do the same. People are moving houses, leaving jobs, leaving seats of power, churches, ending relationships, wrestling with friendships, forming new ones and experiencing ego-deaths.

Like my cousin, some people are exchanging adolescence for adulthood. Others, like my great-grandmother, are exchanging their earthly bodies for their spiritual ones.

In this moment individually, politically and spiritually - it seems like we’re collectively being asked the question: what are we needing to let go of? and then what do we need to welcome in? What fears, habits, thoughts or behaviours need to be given to the earth? What cycles or patterns do we need to bury and mourn so that we can usher in new and better ways of being?

When life asks us questions like this it can feel overwhelming or intimidating to confront, but it is always necessary. I have found that when you do not allow yourself to grow out of old skin you will suffocate within it. The times of transition that we find ourselves in ask us to trust that something greater is unfolding. They ask us not to resist change but to flow with it. Not to forsake the present or the future by holding on to what has gone to the grave, but to be open to what is next.

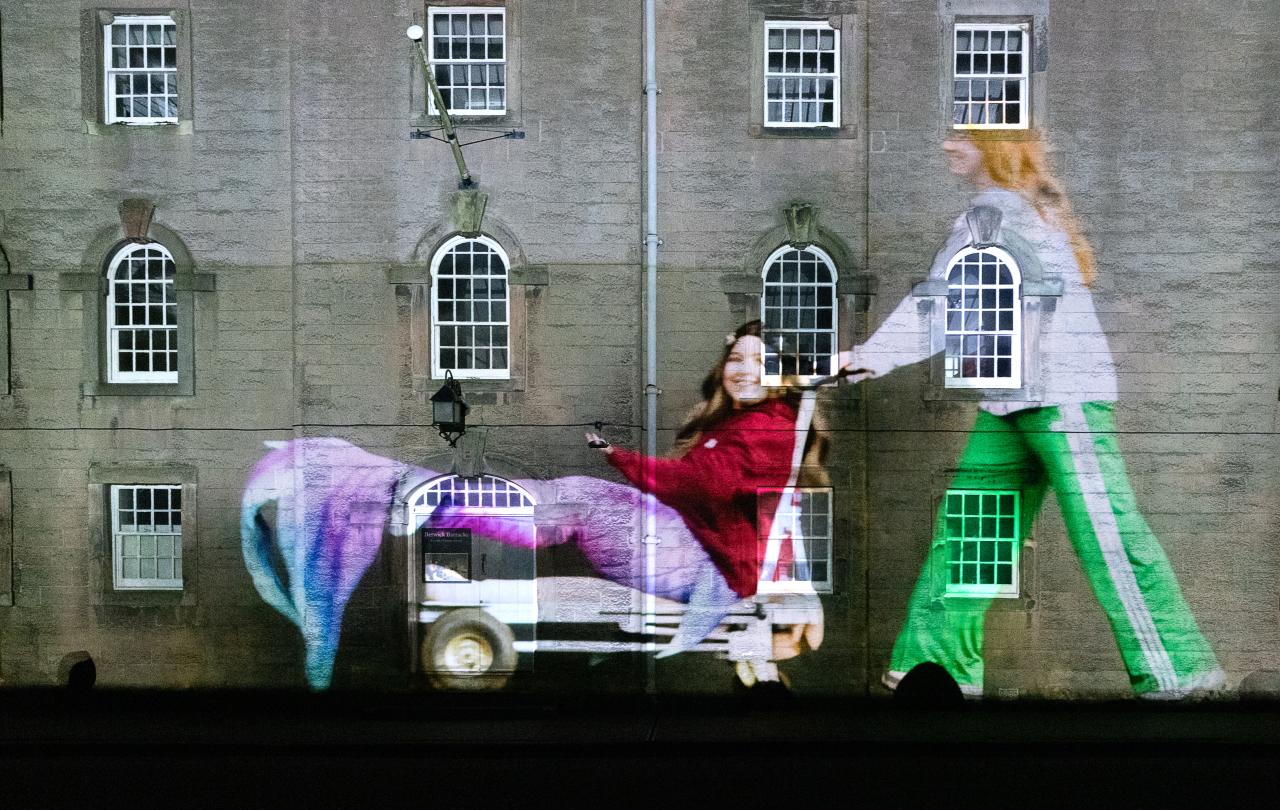

As strange as it was last week to celebrate a birthday after a funeral, it was a reminder that though endings are painful we can embrace them because they usher in new beginnings. It was a reminder that funeral clothes can be exchanged for dancing shoes and that mourning can be exchanged for joy.

Overall, the day was a reminder that if we make room for it, life can follow death, both in this earthly life, and into the next.

Selah.

This article was first published on Substack. Follow Mica there.