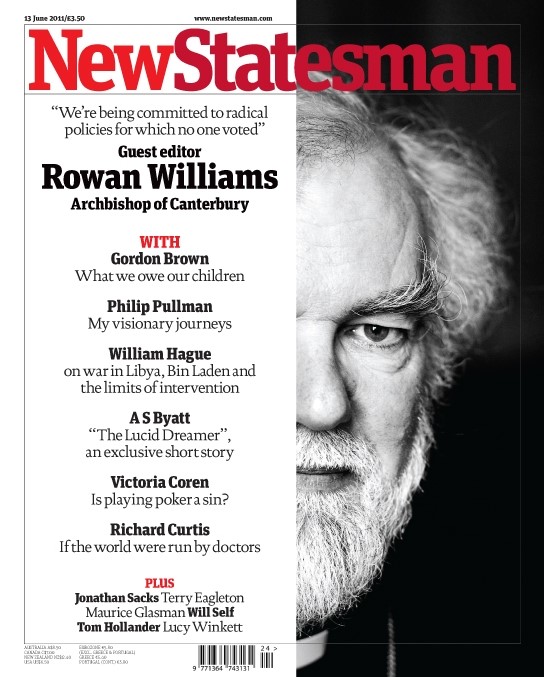

I still treasure my copy of the New Statesman from almost exactly 13 years ago, which was guest edited by the then Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams. I’ve kept it partly because I organised the edition and deputy edited it on his behalf. And partly because it cost me my job as public affairs chief at Lambeth Palace after it provoked predictable Conservative backbench fury for his alleged meddling in politics.

Digging it out now, there are some surprises from near that beginning of the 14 years of Conservative rule that’s expected to come to its end this week. The first is how mild mannered is the archbishop’s leader comment that cause so much trouble. In the years since, politics has become brasher and blunter, more facile and reductive.

The second surprise is the fuss it caused at the time. Williams is politely critical of politics across the board and there’s a plus ca change moment when he wonders “what the left’s big idea currently is… we are still waiting for a full and robust account of what the left would do differently”.

And he could be talking about now as he concludes by hoping for a “democracy going beyond populism and majoritarianism… capable of real argument about shared needs and hopes and real generosity; any takers?”

That final question may get its answer this week. But at this distance, the furore that Williams caused in government takes on a different perspective. We can see, partly as a consequence of what’s happened latterly, that he wasn’t really mounting a political argument at all. His was a moral case, a prophetic voice calling out how the government, any government, “needs to hear just how much plain fear there is.”

That fear hasn’t abated 13 years after that article. It has built around a faltering economy, an island mentality inflamed by the perceived threat of migration and a sense that a political elite has abandoned its people.

Political policies alone aren’t going to salve this pain. The response to it needs to be as much a moral as political one, as caught by the headline I wrote above Williams’ piece all those years ago: “The government needs to know how afraid people are.”

The government in power for the past 14 years has chosen not to address, or has ignored, or has been incapable of addressing the morality of our societal decay, favouring instead a search for eye-catching policies and initiatives that it has hoped, admittedly with some success until now, would also be vote-catching.

That it has now run out of road has as much to do with its moral as its political failure. When Williams published that piece, we were talking about the Big Society, the prime minister was on a mission to save the planet and urged us to “hug a hoodie.” Such moral imperatives seem very distant now and a moral degeneration in government has tracked the downward slide of the governing party in the opinion polls.

So we’re not asked just to make a political decision this week. We’re making a profoundly moral one.

We haven’t had a prime minister for whom morality was a governing principle since David Cameron laid claim to one (perhaps disingenuously) in his early days, before being led by his chancellor, George Osborne, into enforced economic “austerity” with surely one of the most cynical assurances of modern times that “we’re all in this together.”

Brexit did for Cameron and his successor Theresa May. She, I believe, is guided in public life by a personal morality, rooted in her Anglo-Catholic clergyman father, but by now there was no room for all that. Her “hostile environment” for illegal immigrants, with vans telling them to go home, was a moral low point which then found its hideous nadir in the Windrush scandal, with elderly people who had lived here all their lives threatened with deportation.

Boris Johnson thought that he could make a political virtue of his immorality, a demonic possession that made him believe that he’d be loved for it. So he fiddled while Covid burned, partying in Number 10 while those who had voted for him were denied access by his rules to their dying relatives.

I wrote in the Guardian that he wouldn’t be able to hide his immorality in Number 10 when he became leader and was sadly proved more right than I could have known. Liz Truss is said to be on an autistic spectrum, which is the kindest way to explain her mini-budget that offered tax-breaks for the wealthiest in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis for the rest of us.

Rishi Sunak is widely said to be a decent man, but it's too late. This government had already rotted from the head – witness the spivs in its ranks hoping to make a fast buck out of the date of the general election.

So we’re not asked just to make a political decision this week. We’re making a profoundly moral one. It’s time to turn the fear that the archbishop observed into moral indignation.

It’s not really about who we want in government. It’s what we need, morally, to expel from it.