Our nativities are full of familiar figures. Mary and the angel Gabriel, Joseph and the landlords of Bethlehem (of varying hospitality), the shepherds above the town and the heavenly host. Finally, there come the three gift-bearers. While familiar, these perhaps remain the most mysterious guests at the manger. Are they three kings? ‘Wise men’? ‘Magi’? What indeed is a ‘magi’?

Most of the features of our nativity come from the first two chapters of Luke’s gospel, but the magi (along with their counterpart, King Herod) are the primary contribution of Matthew’s gospel, appearing in the second chapter. The word used in Matthew is magi (magoi), a term that was often used for the priests of the Persian religion, today known as Zoroastrianism but in Antiquity known to outsiders simply as ‘magianism’. However, in the gospel it is perhaps intended to carry less specific meaning, instead indicating more broadly those learned in esoteric knowledge, hence our common translation of ‘wise men’. We might be reminded of the class of experts who Nebuchadnezzar summoned to help interpret his dreams, over whom he promoted Daniel to be chief. These were people both knowledgeable and practiced in observing the patterns of nature, experts in hidden knowledge and science, propitiating and interpreting the divine, ‘magic’, alchemy, and astrology. Indeed, this is where we get our word magic from. It is someone of this kind who is intended by the other use of ‘magic’ in the New Testament, when in the book of Acts Simon the ‘magi’, having believed and been baptised, asks to buy the power of the Holy Spirit from Peter and John. Whichever definition is intended in Matthew, these are unexpected guests in Bethlehem.

We learn very little further about them besides that they came from ‘the east’, to which they return as mysteriously as they arrived. Might they perhaps have been from one of the neighbouring eastern states that lay just outside the borders of the Roman Empire, such as Osroene, Adiabene, or Armenia, or even from the great Persian Parthian Empire? Parthia and its provinces were named specifically in the Book of Acts, but Matthew’s is a far more ambiguous reference. Indeed, many scholars would question the historicity of the episode of the magi’s visit, seemingly unrooted in time and place in contrast to the historical and geographical grounding of the rest of the gospels, and so clearly serving as a fulfilment of prophecy about the messiah. The old song of Psalm 72 says: “May the kings of Tarshish and of distant shores bring tribute to him. May the kings of Sheba and Seba present him gifts. May all kings bow down to him and all nations serve him.” Elswhere the book of Isaiah records: “The nations will come to your light, Kings to the brightness of your dawn… young camels will come bearing gold and incense, proclaiming the praise of the Lord.” When you see the gift-bearing magi represented as camel-riding kings on your Christmas cards, they are being shown as the fulfilment of these prophecies.

Christians in medieval Europe were dimly aware of just how widespread Christianity was, and they represented this in their stories about the magi.

What is crucially important in their role as prophecy-fulfillers is that they are gentiles. Indeed, they are the first of those outside of God’s chosen people to recognise the Messiah. While Luke shows Jesus announced to the poor and humble among the Jews, rather than the priestly or royal, Matthew shows him recognised by the gentiles, the first trickle of a mighty torrent prophesied throughout the Old Testament: “All the nations you have made will come and worship before you, Lord,” sings the Psalmist. “In the last days the mountain of the Lord’s temple will be established… and all nations will stream to it,” records Isaiah once more. This is echoed also in Micah, the book quoted in Matthew by the chief priests to the magi: “The mountain of the Lord’s temple will be established, and many nations will come and say – let us go up to the mountain of the Lord.” These were outlandish claims and the magi represented the outlandish start of their fulfilment.

Nevertheless, the magi in Matthew don’t float entirely untethered from historical reality, as they act out a story within the solidly historical setting of Herod’s final paranoia. His anxiety about the title ‘king of the Jews’, and his desperate massacre of the innocents both fit with what we know of his last days. For Herod, an Idumean (or Edomite), his questionable Jewishness had been a source of anxiety throughout his life, and he had become deeply unpopular by the end of his life, perceived as far too close to the Romans. Some scholars have suggested that Herod would have found fewer than a dozen infant boys around Bethlehem, as such it is unsurprising that his order is otherwise absent from the historical record. One of the few authors to cover this place and time was Josephus but writing almost a century later, he is much hazier on this period. He does, however, note that at this time Herod’s paranoia had driven him to kill three of his own sons, including his heir, historically much more significant and shocking. Josephus also claims, that on his deathbed Herod gave orders to have all the principal men of the entire Jewish nation killed when he died, to increase the mourning of the people, orders which were not carried out.

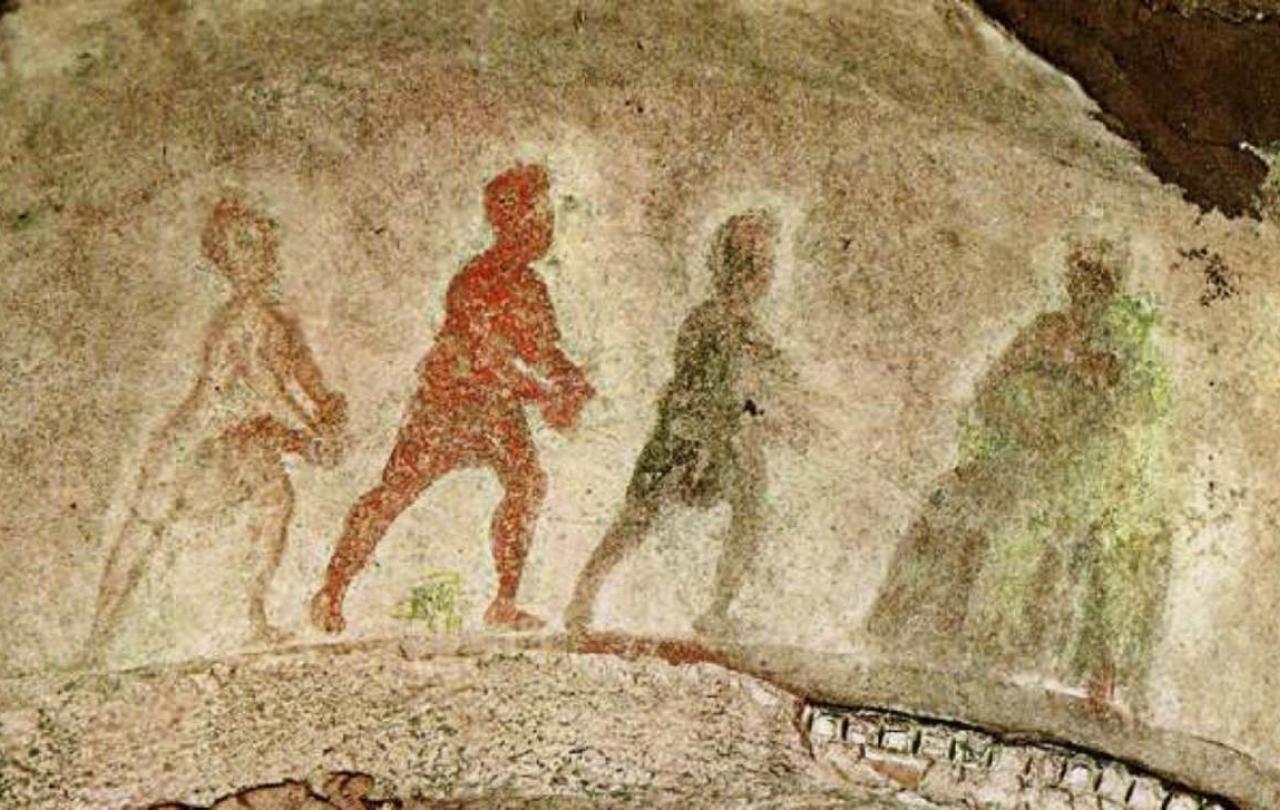

That one day people of all nations and tongues would come to worship the God of Israel is one of the more outlandish claims recorded in the Old Testament. Even for early Christians, who were more actively seeking its fulfilment, it must have remained somewhat unimaginable, given they were still a minority in a corner of the Roman and Persian Empires who knew very well that human societies stretched on beyond their known horizons. By the Middle Ages, it was appearing a lot less outlandish. There were now Christians as far flung as Iceland, China, and Ethiopia. Christians in medieval Europe were dimly aware of just how widespread Christianity was, and they represented this in their stories about the magi. They imagined them as three kings (echoing prophecy and expounding scripture) from the three ‘petals’ of the world which connected at Jerusalem, representatives of the many gentile nations who would embrace the gospel. One for Europe, one for Asia, one for Africa; even in medieval Europe the church was understood as encompassing all three, and the magi were the first indication that it would.

In Asia, ‘east’ of Jerusalem, the magi assumed different significance. Whether in Persia or China, claims were frequently made that the magi had come from their own place or people. Among the Christians of Mesopotamia (covering present-day Iraq and parts of Syria and Turkey), where Christianity had first arrived under the Parthian Empire, various legends were written about them in Syriac (a dialect of Aramaic). Here they often numbered twelve and were claimed as the founders of various churches and villages. Further east, and later, in the thirteenth century, an Armenian Christian lord, Smbat Sparapet, recorded in a letter that, while travelling across the Mongol Empire and visiting Christians in Central Asia and China, he had noticed they all decorated their churches with images of the magi. He recorded that the magi were believed to have originally come from China, from the region corresponding to present-day Gansu province. His brother, the Armenian king of Cilicia (south-east Turkey), who later made the same journey alternatively recorded that the magi had rather come from among the Uyghurs.

The Turfan Oasis, lying to the north of the great Taklamakan desert in today’s Xinjiang province in China, also known as the Uyghur Autonomous Region, was home to a community of Uyghur Christians between at least the eighth to fourteenth centuries. One of the few surviving indications of their presence is a large collection of fragmentary manuscripts, preserved by the dry desert conditions. Among these is a unique legend concerning the magi, originally written in Syriac, but here translated into Uyghur. It preserves the account from Matthew but with some additions. For instance, the identification of the magi with the Zoroastrian priesthood is made explicit, probably owing to the original Syriac authors’ own familiarity living among the ‘magians’ of Mesopotamia. Most striking of all though is the word choice of the Uyghur translator. Approaching the infant Jesus, the magi hail him as ‘Khan Messiah, the son of Tengri.’ The magi’s royal gift of gold recognises Jesus as ‘khan’, a straightforward translation of ‘lord’ but one which carries local cultural resonance. Tengri, however, was the high God of the Uyghurs and Mongols. He was the creator, present everywhere, but associated particularly with the heavens. To see Tengri in Jesus was to see the mighty God who forged their own sky and steppe come to earth as infant and man.

The popular legend that the magi had come from among the Uyghurs, which perhaps motivated this translation, connected their immediate reality to the distant settings of the gospel stories. Like the legends of the medieval west, this too served to communicate the truth that in the recognition of Jesus by the first gentiles, the magi, could be seen the start of the gospel’s journey to all gentiles, all nations, tongues, and petals.

This Christmas, when you see the magi on your cards and in your nativity scenes, or you sing carols about three kings, think about the deep traditions that have formed these images, representations of prophecies fulfilled in Jesus, of the inclusion in the kingdom of all nations and of you too.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief