Just as every coin has two sides, every soul contains the equal capacity for good and evil. Just like affairs of the soul, migration has the ability to strengthen or weaken societies.

Nigeria, the Giant of Africa, has one of the world’s largest and most professionally distinguished diasporas. Over 17 million Nigerians live in other countries. The most famous members of the Nigerian diaspora, figures like Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Anthony Joshua, John Boyega, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Wally Adeyemo, have achieved stardom thanks to talents that impact or entertain millions of people globally.

However, these famous figures merely represent the glorious one percent of the Nigerian diaspora. Their success can easily distract observers from the grim reality of why so many Nigerians desperately seek to leave a country known for producing world changers.

Seeking data on violence

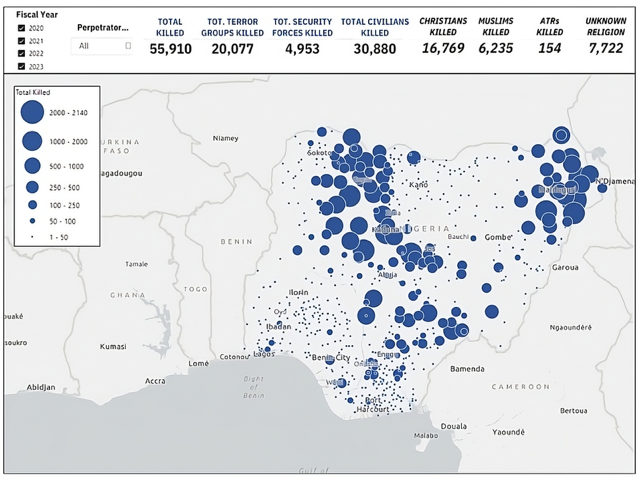

In October 2019, researchers at the Observatory of Religious Freedom in Africa started a project exploring the nature and impacts of of religious violence in Nigeria. The project spanned four years and generated many significant findings. Terror groups in Nigeria killed 31,000 civilians in 7,000 attacks in just four years, the Fulani Ethnic Militia (FEM) accounting for 39 per cent of these killings (a figure dwarfing the killings perpetrated by ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliates), So called “land-based community attacks,” a concept referring to instances when actors like FEM invade small Christian farming settlements to kill, rape, and abduct Christians and burn their homes, accounted for 82 per cent of civilian killings in the study, Christian death tolls far exceeding Muslim death tolls (2.7 Christians killed for every 1 Muslim killed) in the reporting period, and 6.5 times as many Christian murders compared to Muslim murders relative to average state populations.

The methodology of the study set out to find data on all the people, regardless of their religion, negatively affected by terrorist violence. However, with every new batch of data collected, disturbing patterns emerged. Since the 2009 birth of the infamous Boko Haram insurgency, global media coverage of the terrorist violence has consistently argued Muslims rather than Christians disproportionately bear the brunt of this Islamist extremist violence. The findings of the study suggest otherwise.

ORFA data map of fatal attacks across Nigeria.

Shouldn’t the government do something?

Historically, Nigerian governments have been reticent, even reluctant, to condemn violence in the north associated with the Fulani ethnic group. Former presidents like Muhammadu Buhari, a member of the Fulani, have even gone as far as to dismiss the issue of Fulani ethnic violence as just “cattle rustling.” However, in Nigeria, mere “cattle rustling” to some is a seriously grave situation for others.

Findings by the Observatory researchers suggest Nigerian security operatives, most of whom belong to the Fulani and Hausa ethnic groups, have a suspiciously selective way of engaging with terrorist violence in northern Nigeria, often leaving Christians distinctively vulnerable. Roman Catholics in Nigeria have even accused Nigeria's military of being a jihadist force. Churches in northern Nigeria live in a constant state of terror and acutely distressing fear.

In Nigeria, the federal government alone, led by the president, has the final say on matters concerning security and the army. Incumbent President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has notably appointed far more Christians to senior government offices than his predecessor, Buhari. The Nigerian government is famously opaque. Despite its nominally democratic visage, family dynasties and networks continue to dominate political life and business affairs.

Understanding the religious geography and reaction

Religion in Nigeria is divided along geographical lines. The northern half is dominated by conservative Islam. Catholicism and Anglicanism reign supreme in the southeast. The southwest functions as a geographical melting pot of Islam (albeit a more secular variety compared to the north) and Christianity (especially Pentecostalism). The north contains a surprisingly large number of Pentecostals. Many Pentecostal pastors and choirs in the north have been kidnapped by the mercilessly violent Islamist extremists.

The overwhelming majority of Christians in Nigeria live in the southern half of the country. However, in a Nigeria which has suffered from one oppressive government after another for decades (most of these led by conservative Islamic military and civilian presidents), most Christians struggle to survive and lack the energy to speak up for their northern kin. Despite their weariness, the Southern Nigerian Church (the collective population of Christians living in the south) has a sacred responsibility to awaken and demand greater protections from the federal government and the military for Christians living in the north.

Local causes, global effect

Over the last two decades, commentators have routinely pointed to climate change as the primary factor facilitating violent encounters between Muslims and Christians. Fulani cattle herders, guided by the desire for better grazing lands for their livestock, have often encroached on land owned by Christian farmers in the north and middle regions. The findings by researchers at the Observatory suggest significantly more is going on to facilitate these violent clashes than just climate change. Ascribing the challenge of religious violence in Nigeria to just climate change provides a get-out-of-jail free card to the men of violence linked to the orchestrated killings of Christians.

Ethno-religious violence has quietly become commonplace in northern Nigerian life. The single solution capable of curbing this violence is unprecedented, cross-party, interethnic, and interreligious security reform. Strength of security affects every person in Nigeria. From the richest to the poorest, no one is immune from a sudden kidnapping, suicide bomb, or violent act of banditry negatively changing their life forever.

Nigeria's neighbours in Europe cannot afford to continue slumbering and must wake up. Readers in Europe feeling insulated from the violence the data records are just as susceptible to the shockwaves that a collapse of the Nigerian state as other West African neighbours. Such an event would imperil the security of citizens in countries like Italy, Spain, and Greece just as much as it would people living in Mali, Chad, and Cameroon.

Nigeria has never been nearer to a civil war or state collapse since the Biafra War of the late 1960s. Ethno-religious violence disproportionately targeting northern Christians is one of the greatest and most overlooked factors contributing to Nigeria's dysfunctionality. In an unprecedentedly connected world, such a collapse would, in turn, trigger further collapses. The European Union (EU) does not grasp the severity of how such a collapse would affect its own security and stability. At a time when every day brings news of small boats carrying migrants to European shores, Nigeria's collapse would trigger one of the greatest avalanches of mass migration in modern African history.

A modern Middle Passage

Nigeria has a population of over 235 million, the largest in Africa and sixth largest globally. If just 10 per cent of the population attempted to flee in the event of another civil war or a destabilising political event, that is 23 million Nigerians desperately fleeing into any country they reason might welcome them. Many of these millions would gamble by voyaging on the tempestuous Atlantic Ocean in small boats with the goal of beginning new lives in European countries. Some would inevitably perish in what might evolve into this century's Middle Passage. Nigeria’s collapse would destroy the EU by overwhelming its borders and social services. The average population of an EU country is just under 17 million, or the size of Nigeria's diaspora. The unprecedented connectedness of our world means catastrophic destabilisation in one country can have significant consequences for the stability of other countries globally. The EU has a geopolitical responsibility to invest in improving Nigeria's security situation. Abductions, killings, and displacements in Nigeria might trigger instability in Europe and beyond.

However, the collapse of Nigeria would not only destabilise the EU. ISIS affiliates like ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province) have a strategic interest in Nigeria's collapse, because it would open the door for them to expand their control throughout West Africa.

A team of researchers guided by the goal of better understanding terrorist violence in Nigeria simply followed the breadcrumbs of organically emergent data to show why the broader world should take seriously violence against Christians in the Giant of Africa. Living in an unprecedentedly connected world comes with new privileges and new responsibilities. To simply indulge in these new privileges without standing strong and shouldering these new responsibilities would be foolish, selfish, and nearsighted.

English poet John Donne once famously wrote,

No man is an island,

Entire of itself, of the continent,

A part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less.

Every man is a piece.

The “old self” understanding of global connectedness, ruled by selfishness and ignorance, must give way to the “new self” model of prosperity and security via proactive collaboration. For every one Okonjo-Iweala, Boyega, or Antetokounmpo, millions of Nigerians suffering from the effects of a rapidly destabilising state dream of emigrating abroad. Global Christianity and global security stakeholders each have an interest in a stable Nigeria. A stable Nigeria functions as a wellspring of human capital for the benefit of the entire world.

Donne, in the same poem, wrote,

Each man's death diminishes me,

For I am involved in mankind.

Therefore, send not to know

For whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.

The world is involved in Nigeria and Nigeria is involved in the world. The death of Nigeria would pave the way for the death of the EU. The bell tolls for the EU community to awaken from decades of neglectfully overlooking its interests in a stable and secure Nigeria.

Further resources

- ORFA report summary.

- ORFA full report.

- 'No Road Home', a data study on those living in displaced persons camps. Download the study (PDF).