In the final room of this year’s Turner Prize exhibition hang portraits drawn by Claudette Johnson. Monochrome pastel, blocks of coloured gouache, and the contours of Johnson’s “raggedy” lines combine to depict black women and men. Many of them are Johnson’s own friends and relatives. These are monumentally large drawings, often spanning several meters; faces and bodies rendered unmissable. I think of these portraits in between the gallery’s opening times. In the stillness of the small hours, lights off, there they still are, eyes open, in no need of our gaze to make them real. Each emphatically there.

Johnson’s point is in part political: the presence she conjures is of those who have largely been absent from the canon of art history. These are works of redress, asserting the properness of Black presence and agency in a tradition at best closed and at worst profoundly hostile to such subjects. Readings of Johnson frequently underscore the labour of her portraiture in exactly this way: They weren’t there. Now they are. But to stop here risks relegating the presence Johnson invokes to a matter of mere attendance.

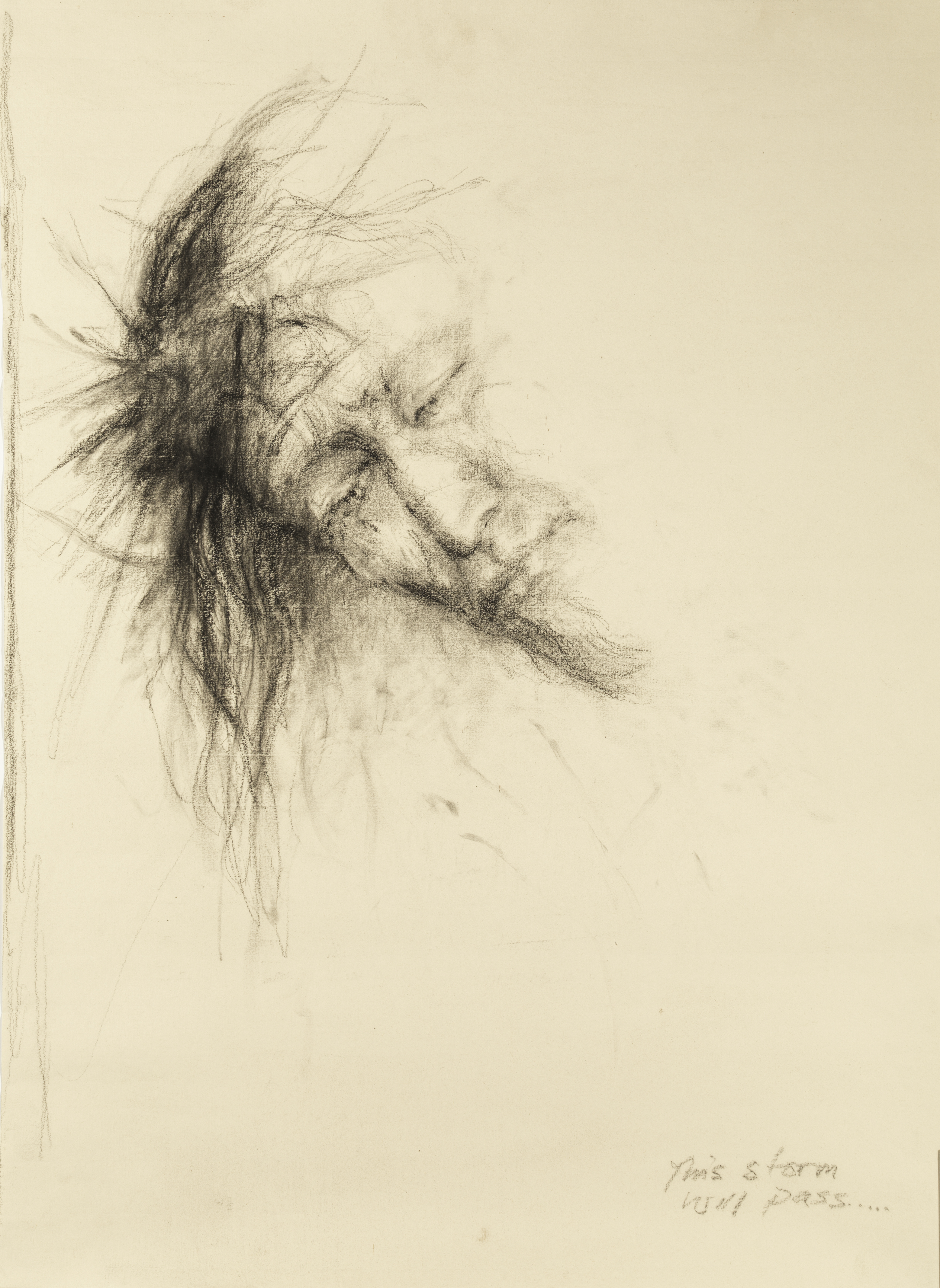

It’s not just that Johnson’s subjects are there, present and correct, but that they are there, emphatically there, allowed to be there with an imprecision and capaciousness that ultimately evades our grasp. So many of her figures appear a moment away from motion - twisting, curling, stretching, turning - on their way to some other pose not yet found. They are regularly clipped by the boundaries of her paper, slipping beyond an edge into the void of the gallery wall. Johnson’s own marks can seem to wane, from the fine shading of a face at the top of a piece, to the erratic jolts that give way at its bottom (Figure with Raised Arms 2017). The waning mark reads as a confession: I cannot capture the whole of what is here. Several of her works are interrupted by swathes of space untouched apart from a sketchy single line. In such works, bodies are outlined like unchartered territories, whole untouched worlds still evolving (Reclining Figure 2017). The presence Johnson conjures is of lives still being lived and worked out. Unhemmed by definition, malleable and alive, her subjects become more than we can see or say.

In an interview earlier this year, Johnson spoke of her intention to ‘resist the urge to present heroic figurations… that offer a radical alternative to the negative imagery out there’.[1] I am reminded of a distinction theologians have worked with to distinguish angels from humans. Angels, outside of time, choose an orientation ‘once and for all’. The angel manifests their orientation to the divine forever and always, defined by that single choice. Humans by contrast, enduring in time, cannot give the whole of themselves over to any one thing completely. They are in motion. They cannot be fixed in one orientation forever. But that unfixed-ness, that distinctive plasticity, that lack of definition, is part of their crowning glory. It’s what permits human beings to image a God who himself is without bound, limit, or definition.

Johnson does not make her subjects into heroes or angels. The presence possessed by her portraits is neither precise nor still. It’s the presence of humans allowed to be humans. Humans who, in their distinctive glory, squirm and turn and dream and regret, who forgive and are forgiven, who change their minds, who grow and wonder and forget and remember.

Support Seen & Unseen

"If you were able to support us on Seen & Unseen with a regular gift of £5 or £10 a week, that would be a great encouragement for us and enable us to continue to produce the content we offer."

Graham Tomlin, Editor-in-Chief