When I felt a twinge in my lower back at the age of 30, little did I know that this would lead to chronic pain for over 20 years and counting. Defined as persistent or recurrent pain that is present for more than three months, chronic pain can lead those of us who battle it to struggle to carry out daily activities or to socialise freely. Research shows that up to 15 per cent of the UK’s population live with pain that is moderately or severely disabling. Whether discal, muscular, arthritic, or related to auto-immune or other conditions, medical researchers inform us that we are facing a silent epidemic of chronic pain in our society.

In the past 20 years, pastoral work has opened my eyes to the fact that those of us who face the ignominy and anguish of chronic pain cannot claim a monopoly on suffering. No stranger to significant hardships himself, psychologist and Auschwitz-survivor Viktor Frankl suggests that all suffering should be taken with utmost seriousness, however brief or minor it proves to be. The “size” of suffering, after all, is relative. It is, he claims, like releasing gas into an empty chamber – it doesn’t matter how much gas is released, it will fill the chamber completely. In other words, it does not matter how great or small our sufferings are, they will always hold the potential to darken our hearts completely.

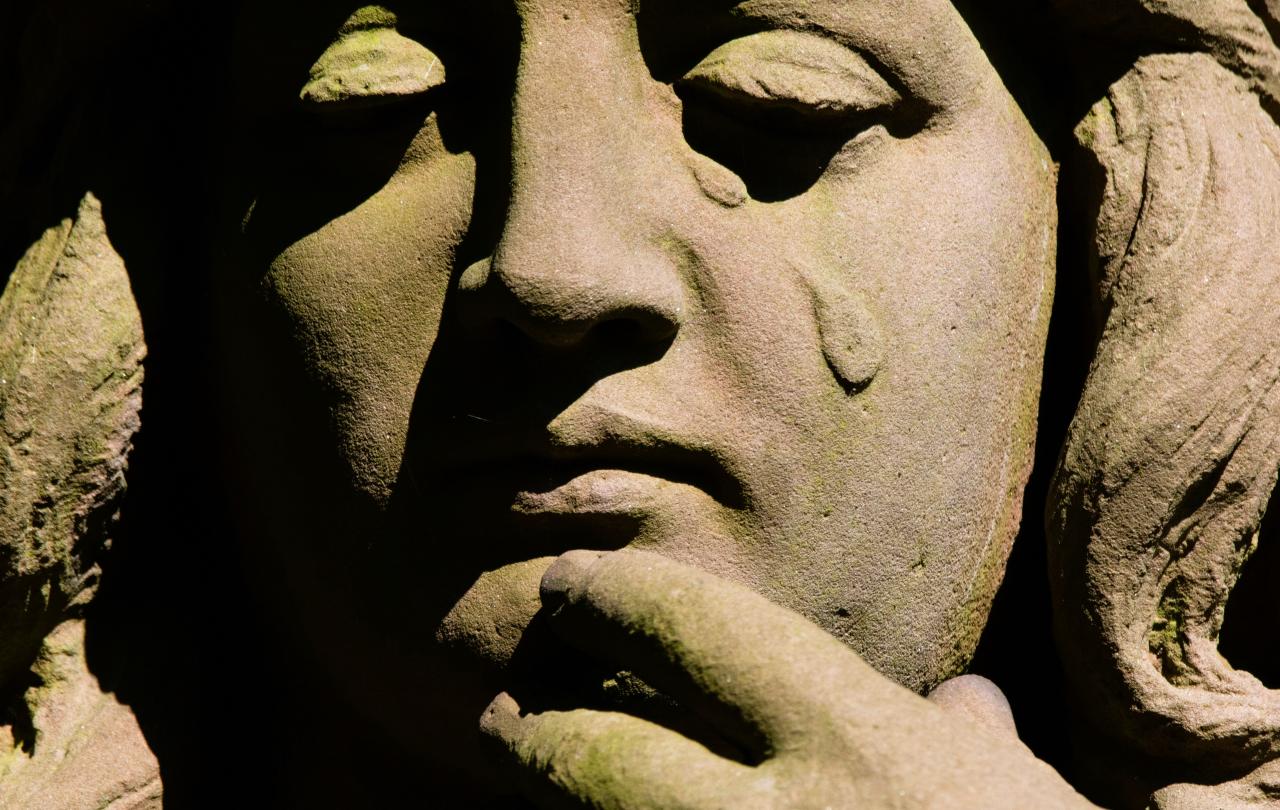

Behind even the brightest smiles and the most cheerful demeanours are the scars of a thousand cuts.

Suffering and struggle have been particularly marked in our society in recent years, with the twin-tribulation of the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis leading to so much grief, illness, depression, loneliness, poverty, and isolation. Some years back, I undertook hydrotherapy at the local hospital. With each patient having endured various injuries, many quite serious, I was struck by the plethora of scars in the pool each week – on backs, shoulders, arms, knees, and ankles. The many years of struggle and pain in that pool was all too visible, but, as I undertook my aquatic exercises, I recall thinking to myself: if we could peer into the souls of those around us, how many more deep-seated scars would we notice? Behind even the brightest smiles and the most cheerful demeanours are the scars of a thousand cuts.

Neither should we fall into the trap of believing suffering merely impacts us as we age. While it is true that there is a correlation between age and bereavement, illness, and disability, the dark hand of suffering is not partisan to age or circumstance. Many children and young people go through all manner of serious trauma and illness, often hidden to those on the outside. Research is showing a sharp rise in chronic pain in young people, for example, while teachers bear testament to the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of so many of their pupils. Moreover, when I was a university chaplain, I saw how deeply young people were affected by incidences and events, even those that, to others, may have seemed trivial. Younger generations are certainly not immune to life’s struggles.

Like that tenacious and resilient tree breaking through the harsh concrete, we witness hope and promise shining out of the pages of his letters.

Christians, of course, have always been aware of the philosophical questions surrounding the existence of suffering. The book of Job in the Old Testament details one of the earliest attempts to consider theodicy, while numerous scholars down the ages have grappled with the “problem of pain” (C.S. Lewis) and the question of “where is God when it hurts?” (Philip Yancey). Their musings are well documented and discussed, but, as a Christian with chronic pain, I have become less interested in the “why?” of suffering and more concerned with the “what now?” In other words, I am increasingly interested in how faith responds when confronted with the crippling and dehumanising personal impact of pain, grief, illness, disability, relationship break-ups, depression, loneliness, poverty, or anxiety.

During a particularly acute flare-up of back pain recently, I took short walks around our immediate locality. We live in a concrete jungle – there are houses, streetlights, cars parked down both sides of the road, and vehicles driving up and down, especially at school drop-off time. In my pain, I was struggling to see any hope in the incarceration of a city. Then I noticed something on our road that I’d walked past on many occasions. It was a small, solitary tree, which is about twice my height. For a brief moment it lifted my heart and I thought to myself how wonderful that someone had planted that tree, just to give some greenery to this urban sprawl. But then I noticed that this beautiful little tree had not been planted at all. Rather, it had broken through the hard, unforgiving concrete, desperate to reach up to the sunlight and take in the oxygen in the air. That small tree is, in many ways, an apt metaphor for the Christian response to personal suffering.

From the book of Acts and his letters in the New Testament, it is clear that St Paul had walked the gruelling path of pain and struggle. He faced prejudice, persecution, and prison, not to mention his battle with a personal affliction, which he called a “thorn in my flesh”. Scholars posit this may have been an illness or a disability, such as blindness. Yet Paul does not allow his letters to become dark, depressing diatribes of fear and hopelessness. Like that tenacious and resilient tree breaking through the harsh concrete, we witness hope and promise shining out of the pages of his letters. Here was a man who knew suffering, but, through his vivid encounter of the person of Jesus, he had also grasped the profound meaning of hope. When we attend a funeral or a wedding, we will quite often hear uplifting passages of hope and joy written by him. Discussions around the tension in Paul’s epistles between “flesh” and “spirit” are well worn, but, when I read his letters, especially in light of the life and death of Jesus, it is the tension between “suffering” and “hope” that is most conspicuous.

“I have seen the light – it flickers on and off like a badly-wired lamp”.

This tension, of course, is not just prevalent in the Christian scriptures. It is hard-wired into the human condition. Just take the years of the pandemic, when people were either isolated, lonely, stressed, and anxious themselves or were journeying alongside others facing illness, grief, worry, and fear. During that period, I was a parish priest and would regularly visit people, standing socially distanced on their doorsteps. Yet, despite suffering seemingly being omnipresent during the pandemic, people did not generally regale me with their miseries. Rather, they wanted to inform me of moments of uplifting hope that had broken through their difficulties – the beauty of nature on their daily walks, the tireless care of the NHS workers, and the joy of meeting with friends and family, on zoom or outside in the garden. They seemed naturally aware that hope and suffering are inextricably linked. This fact is at the heart of our Christian experience – its recognition is one of those things that define Christians as Christian. After all, the very symbol that has come to represent the Christian faith – the cross – is both an emblem of torture and suffering and a symbol of liberation and hope.

Not that opening our eyes to moments of hope, love, and wonder is easy when we are going through difficult times. In the dark moments when my own chronic pain seems overwhelming and utterly debilitating, I am inspired by the words of the former poet laureate Andrew Motion: “I have seen the light – it flickers on and off like a badly-wired lamp”. There will be times when Christians will see God’s light clearly and its beauty and glory will dazzle daily. But there will also be times of doubt, grief, depression, anxiety, and physical pain. During those moments, we can learn to be sustained by the occasional spark of hope that will come to us, even in the very ordinariness and humdrum of our daily lives.

And so, in travelling through life’s dark moments, Christians recognise two powerful realities. One of these has long been championed by preachers and spiritual teachers – it is the presence of a kingdom to come in a heavenly future where there will be no more tears and no more suffering. The other one, though, can speak powerfully into the present predicament – it is the presence of a kingdom all around us now, breaking through the harshness and bleakness of life, like that small tree bursting through hostile concrete. Theologians refer to these two realities as “inaugurated eschatology” and they can also help us to recognise profound moments when transcendent hope breaks into our lives. Opening our eyes to compassion, beauty, wonder, and awe can help us transcend our suffering, which so often seems all pervasive, and can lead us into a strange new world of God’s providence.

In the soil that the broken concrete had revealed were little green, sprouting shoots. Hope had begotten hope.

So, Christians hold onto the hope of the “not yet”, confident in the hope of life after death. But, as the old Christian Aid advert put it, we also believe in life before death. However dark and long our journey seems, hope is birthed when we take time and space to notice strange and uplifting moments of beauty, grace, and guidance breaking through our daily lives now. In these, Christians find, in the words of theologian Karl Barth, “indications, intimations and parables” of the coming reign of God.

After 20 years of daily struggle, I have made peace with the fact that I am likely to battle chronic pain for the rest of my life. However, I have also come to recognise that hope is not all about smiles, sunshine, and flowers. Hope is often difficult and demanding. It is about delicately holding the joy and challenge of life in a wonderful balance. For the Christian, it’s about both recognising God’s kingdom in the beauty, awe, and wonder of his created world and glimpsing it in our very earthly, wearisome, and draining lives.

But there was also something else about that small, resilient tree that was breaking through the hard and unforgiving concrete. On another walk, a few weeks later, I noticed foliage growing around the base of the tree. In the soil that the broken concrete had revealed were little green, sprouting shoots. Hope had begotten hope. And it is certainly true that the more we open our lives to recognising hope, however brief it may be in our struggles, the more it can inspire us to bring moments of light and comfort to others. And thus we live out, in the words of Karl Barth, so many “little hopes”, and, by doing so, we scatter seeds of new life and resurrection as we go, trusting that God will water them and bring his “hope, faith, and love” to fruition in the world around us.