Everywhere is Heaven is an art exhibition of work by Stanley Spencer and Roger Wagner at the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham. It’s the English village where Spencer lived most of his life and which he described as a “village in heaven”. ‘Everywhere is heaven’ is also a description of sacramental theology and a theme for British Visionary artists from William Blake to the present day.

Everywhere is Heaven is the gallery’s first collaboration with a living artist. Wagner has been deeply inspired by Spencer’s paintings, viewing Spencer as being “an artist who seemed to be doing exactly what I wanted to do”.

The work of these two artists has been brought together, in part, because both work in the tradition initiated by the visionary poet and artist, William Blake.

Both artists have been described as “visionary geniuses”, each seeking to evoke the mystical in everyday experience. Spencer depicted Cookham as ‘heaven on earth’ writing that “After steeping myself in the Bible I began to realise certain things equally inspiring to love, outside the Bible”.

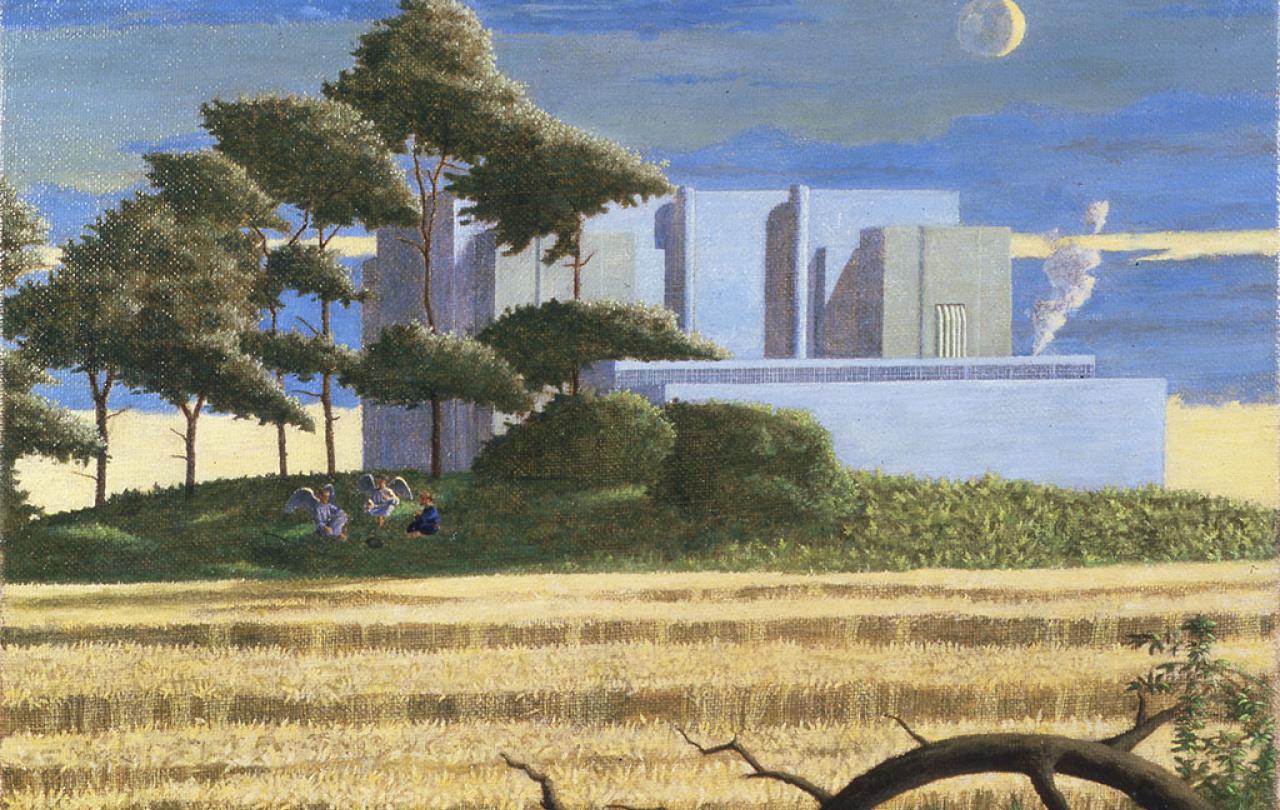

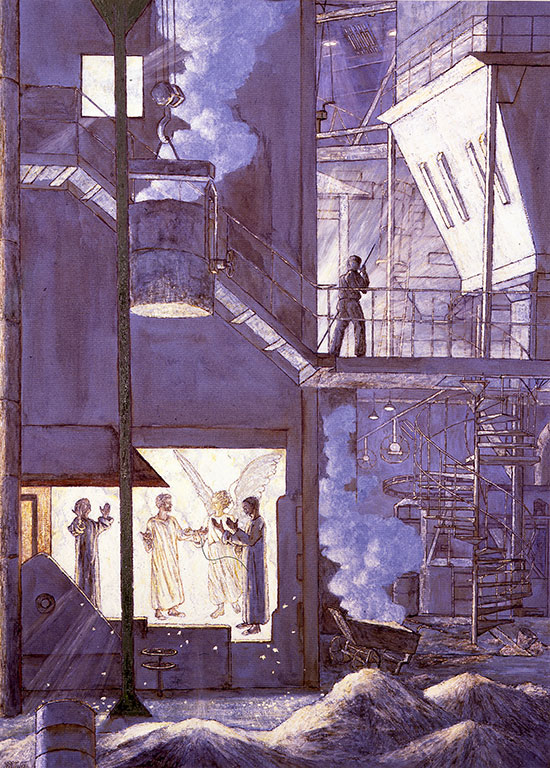

This was the point when the holiness of things began to strike him meaning that he “became extremely busy, first at the front door and then at the side and back entrance of the Kingdom of Heaven, a place long familiar to me, but not in this new and significant way”. This was because “art seemed the only thing which revealed Heaven”. Similarly, Wagner, in paintings such as Abraham and the Angels or Walking on Water III, also evokes biblical happenings in contemporary settings. Exhibition curator Amanda Bradley Petitgas writes that “Wagner’s very human, sympathetic, biblical figures … inhabit our own modern world; we find Peter walking on the water in front of Battersea Power station, or Abraham quietly contemplative in front of Sizewell A nuclear power station”.

Stanley Spencer: John Donne arriving in Heaven 1911.

Both are united by a love of “metaphysicals”, as Spencer described the metaphysical poets, with John Donne and Thomas Traherne, a theologian who wrote with a visionary innocence and found mysticism in the natural world, being particular influences. The title of the exhibition references Spencer’s own words about his painting, John Donne arriving in Heaven, and his description of the four figures facing in all directions because “everywhere is heaven so to speak”. Bradley Petitgas writes “that both Spencer and Wagner’s visionary innocence and the ability to find mysticism in the natural world” echo that found in the work of Traherne. While also noting that Wagner’s “deeply Christian paintings are founded on iconographical orthodoxy, each one a balanced expression of quiet beauty and accessible humanity – ‘heaven in ordinary’, to cite George Herbert”, another metaphysical poet who is key to Wagner’s vision.

The visionary tradition

The work of these two artists has been brought together, in part, because both work in the tradition initiated by the visionary poet and artist, William Blake. As Anthony Mould writes, “These are two painters that combine a type of Englishness to be found in William Blake’s ‘ancient time’ within a ‘landscape’ of their own familiarity”. The artist Betty Swanwick once described being part of "a small tradition of English painting that is a bit eccentric, a little odd and a little visionary". This is a tradition that begins with Blake and continues through Spencer to contemporary artists like Wagner. In briefly exploring this tradition further I shall introduce some of the other artists who also engage with their ideas and approaches.

A recent exhibition William Blake: Prophet Against Empire argued that Blake “responded to the tumultuous times he was living through as he witnessed the expansion of the British Empire, American Independence and the French Revolution” with “imaginative images and texts that resonated with this changing world” and which took a “critical stance against the Age of the Enlightenment with its emphasis on science and reason”. “Drawing on his deeply felt religious beliefs, Blake criticised empire, slavery and social inequality through his work” in order to create “an alternative universe that celebrates the imagination and communal kindness, where we can also rekindle our connection with the world around us”.

Blake’s visions were of spiritual reality breaking into the material world, so Christopher Rowland writes that the turbulent years of Blake’s life informed “his prophetic understanding of history”. His prophetic images and texts “were ‘prophetic’ not because Blake sought to predict what was going on—indeed they were written following these events”, rather, “he sought to plumb the depths of the historical and social dynamics which were at work in them”. Blake was “part of a tradition of radical non-conformity in English religion, with different ways of reading the Bible” which linked “the personal and the political”. Blake’s vision ultimately was one of building Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land.

Samuel Palmer knew Blake and was part of a group of artists known as ‘The Ancients’ who were his followers. Simon Court writes that as “deeply religious man, Palmer understood himself to be using his heightened perceptions to reveal (at least partially) a divine reality in nature” so that the Kent landscape of Shoreham, where ‘The Ancients’ were based for ten years, “becomes a little heaven on Earth”. David Jones, a contemporary of Spencer, spent his life creating poems and paintings that re-call before God events in the past so that they become here and now in their effect on us. He wrote of the Mass or Eucharist as being to do with the re-calling, re-presentation and re-membering of an original act and objects in a form that is different from but connected to the original act or object that is being recalled. His poems and paintings mirror the action of the Mass and so create a world that is a Eucharist. Fiona MacCarthy suggests that Jones combined the visual and verbal with a “creative intensity not seen in Britain since the time of William Blake”.

Among contemporary artists working within this tradition is Greg Tricker whose profound and simple style of paintings follows in the mystical and sacred tradition of art akin to the work of Georges Rouault and Cecil Collins. Qualities of myth, echoes of the Folk Art Spirit and elements of the circus feature in his work, which he often presents in themes; notably Paintings for Anne Frank, The Catacombs, and Francis of Assisi.

In understanding the ideas and approaches of artists in this tradition, including Spencer and Wagner, we need to turn to sacramental theology. Sacraments are things of the Church which are set apart and made holy. A sacrament is a pledge of God's love and a gift of God's life. Jesus took earthly things, water, bread and wine, and invested them with grace. A sacrament is therefore an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace. As a result, each day can be a sacrament if we practice a way to live life by recognising that God is present in each and every moment and with a selfless abandonment to God as a means of achieving grace and conquering pride and ego.

The Celtic Christians had this sense of the heavenly being found in the earthly, particularly in the ordinary events and tasks of home and work. They also sensed that every event or task can be blessed if we see God in it. As a result, they crafted prayers and blessings for many everyday tasks in daily life. The French Jesuit priest and writer Jean Pierre de Caussade spoke about 'The Sacrament of the Present Moment' which, as Elizabeth Ruth Obbard writes: “refers to God's coming to us at each moment, as really and truly as God is present in the Sacraments of the Church ... In other words, in each moment of our lives God is present under the signs of what is ordinary and mundane.” The philosopher, Simone Weil, stated that this kind of looking, which is the way in which artists such as Spencer and Wagner look, is prayer: “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.” “Absolutely unmixed attention”, she claimed, “is prayer”.

When we pay attention to life in this way, we are, like Spencer, Wagner and other Visionary artists, looking with expectancy for a revelation of the divine in the ordinary sights, events, tasks and people that surround us. We are, in essence, praying the Lord’s Prayer, “your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as in heaven”. Indeed, not just praying it but living and being the Lord’s Prayer. That is sacramental theology, and it is what characterises the vision of Spencer, Wagner and other Visionary artists; as a result, in their eyes, everywhere is heaven.

Everywhere is Heaven: Stanley Spencer & Roger Wagner, until 24th March 2024, Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham.