We all know that asking questions is important. Asking the right questions is at the heart of most intellectual activity. Questions must be encouraged. We know this. But are there any questions which may not be asked? Questions which should not be asked?

Many a young adult might instinctively say “no: never! All questions must be encouraged!” but when invited to think it through, they will come to realise that there is a little more to it than that. There are, for example, statements which present themselves in all the innocent garb of questions, but which smuggle in nasty and false assertions, such as the phrase “why are blond people intellectually inferior to dark people?” There are questions which mould the questioner, such as “will I feel better if I arrange for this other person to be silenced?”

Questions can serve horrible purposes: they can focus the mind down a channel of horror, such as, “what is the quickest way to bulldoze this village?” Even more extreme examples could be given. They make it clear that not all statements that appear to be questions are primarily questions at all, and not all questions are innocent.

Every question is a connector to all sorts of related assumptions and projects, some of them far from morally neutral.

On reflection, then, it becomes clear that every question you can ask, just like every other type of utterance you can make, is not a simple self-contained thing. Every question is a connector to all sorts of related assumptions and projects, some of them far from morally neutral. This makes it not just possible, but sometimes important and a matter of ethics and duty, not just to refuse to answer, but to raise an objection to the question itself. More precisely, one objects to the assumptions that lie behind the question, and which have rendered the question objectionable.

“Have you stopped beating your children?”

“Tell me, my daughters … which of you shall we say doth love us most?”

“How do you reconcile your rationality with your religious faith?”

In all three cases the question is itself faulty. It is at fault because it has brought in an unjustified and untrue assumption. Such questions have no answer except to object to such assumptions and try to help the questioner see the situation more truthfully.

In the first case, if the question is pressed, and I am hauled up before the judge in a court of law, then I will protest, with a clear conscience and as forcefully as I can, that I never did beat my children in the first place and therefore the question is itself at fault. (Such a question is like the unethical practice called “leading the witness” which a good judge will rule out of order in a court of law.)

The second example is the question asked by King Lear in Shakespeare’s play. The play revolves around the fact that Lear has misunderstood the very nature of love. The one who loves him best will not, and cannot, reply in the way he anticipates. His daughter Cordelia chooses largely silence, and to show her love by her behaviour.

The third question is the one that prompted this article. I have been asked it, either explicitly or implicitly, many times. Every time I have been aware that the very atmosphere of the question has prejudged the issue. It is like being asked whether you have stopped beating your children.

To be fair, it is not as bad as the children example, but I use the comparison to help the reader get some sense of the issue. In the case of faith and reason, for any reasonable person, no reconciliation is required because their faith was never divorced from their rationality in the first place. Rather, the two have walked along together, each moulding the other from the start. Being asked to explain this is like being asked to explain that you are honest.

This is not to say that a dishonest or confused person might well have cognitive dissonances - muddles and inconsistences between what they tried to trust and what they had sufficient reason to believe. So, they would have some intellectual and spiritual work to do. And none of us is perfectly honest and clear-headed so we all have some learning to do. But most of us are not starting out from a place of complete dishonesty or contradiction. In particular, our scientific understandings and religious commitments are not pulling in different directions, as the dubious question seems to assume they are. Rather, the deeper our understanding of each, the deeper our appreciation of their roles as two aspects of a single dance becomes.

I recall clearly a discussion with a friend by the side of a football field where our children were playing in a match. The subject turned to religious matters and, with a view to briefly describing his position, my friend said he based his conclusions on reason, and then gestured to some vague idea that I had something else called faith. The obvious implication was that his conclusions had a basis in reason and mine did not. This was not argued or demonstrated; it was the very starting-point of the way he thought the conversation should operate. This floored me. What could I say? It was like being told you are a sub-species, some sort of childish person who does not appreciate reason and therefore should shut up while the adults are talking. (It was also a bit like an amateur wrestler thinking he could advise Muhammad Ali on how to box).

What about the questions which betray assumptions which are themselves questionable, but which we don’t recognise as such, because of the assumptions of our culture and the intellectual habits it promotes?

Now we have arrived at the point of this article, which is not, I will admit, the general issue of questioning the question, but the specific issue of religion and rationality. I want to focus attention on where the issue of questioning the question really lies. The issue is not, “are there questions which are objectionable?” (we already settled that). Nor is it, “let’s have some intellectual amusement unpicking what is objectionable about some ill-posed question which we find it easy to tell is ill-posed.” No, the heart of this issue is: what about the questions which betray assumptions which are themselves questionable, but which we don’t recognise as such, because of the assumptions of our culture and the intellectual habits it promotes?

For example, where do you start in response to a question such as “how do you reconcile science and religion?”

I think you start by pointing out that if one has a healthy version of both then they are not estranged in the first place.

In order to show this, the discussion has to unpack the difference between a valid and invalid grasp of the nature of scientific explanation, and the difference between healthy and unhealthy religion. It will also include some effort to clarify what a person means by the term ‘religion’. The discussion may include some consideration of the history of science, and the lived experience of a research scientist. It should also bring in the brave efforts of reformers down the ages to realise fairer forms of human society.

In the room when it happens

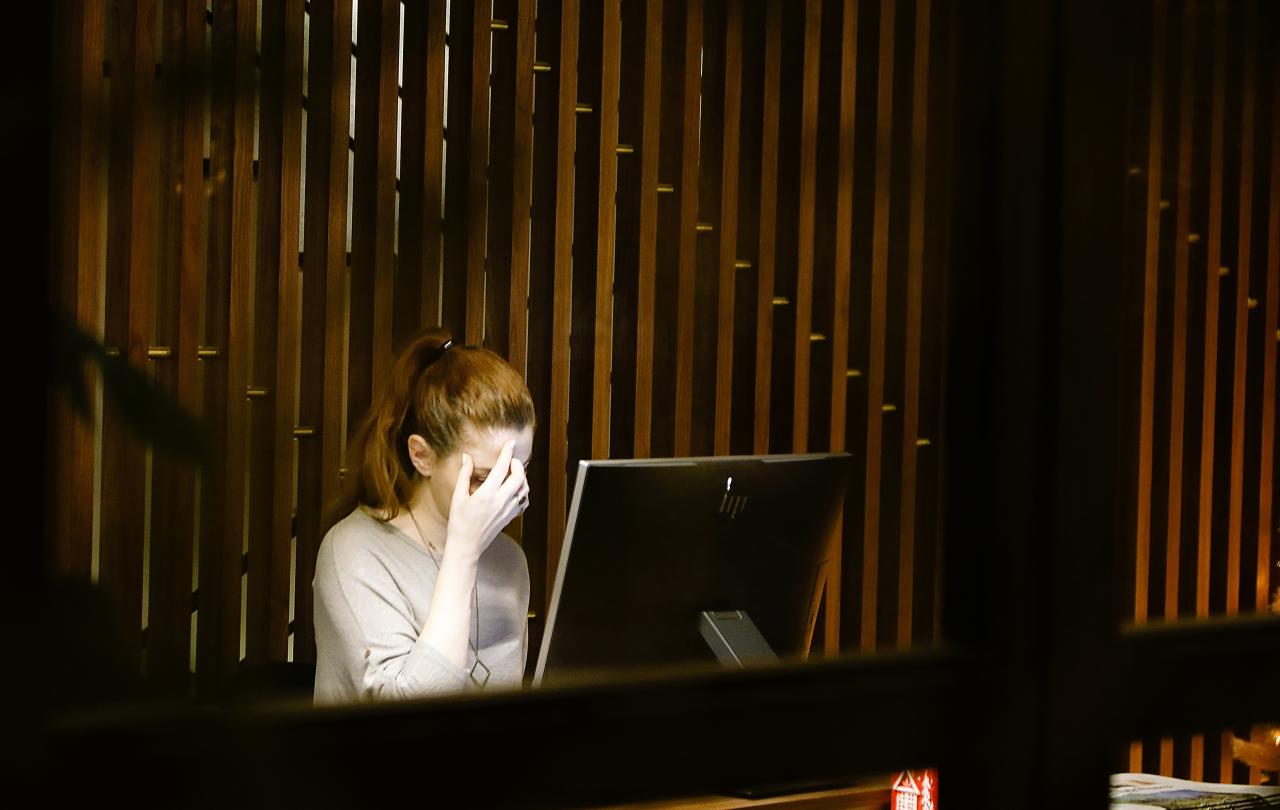

But in order for this discussion to get going, there has to be some oxygen in the room. I have been in rooms where the question, “how do you reconcile science and religion?” has made me feel every bit as queasy as the “beating your children” one. The hollow feeling of having been pigeonholed before you can open your mouth. The feeling of being in the presence of people whose mental landscape does not even allow the garden where you live. The feeling of being treated like a mental underling - it is all there. My reaction is strong because rationality is a deeply ingrained part of my very identity. It is every bit as important to me as it is to the self-declared ‘rationalists’, so that to face a presumption of guilt in this area is to face a considerable injustice.

On the other hand, religion is a broad phenomenon, having bad (terrible, horrendous) parts and good (wonderful, beautiful) parts, so the question might be a muddled attempt to ask, “what type of religion is going on in you?” It still remains a suspicious question, like “are you honest?” but in view of the nastiness of bad religion, perhaps we have to live with it. Perhaps we should allow that people will need to ask, to get some reassurance, and to help them on their own journey. But we can only make a reply if the questioner does not come over like an inquisitor who has already made up their mind. The question needs to be, in effect, “I realise that we are both rational; would you unpack for me the way that rationality pans out for you?”

We all go forward in our lives with some sort of reliance on the ultimate well-spring of reality, whatever that is. We can’t do anything else.

Faith, in its healthy forms, is a kind of willingness. It is a willingness based on a combination of suggestive evidence, value, and lived experience. We all go forward in our lives with some sort of reliance on the ultimate well-spring of reality, whatever that is. We can’t do anything else. The faith which is called religious may include willingness to acknowledge this ultimate well-spring of reality in personal terms. We may express gratitude, for example, and objection, and we may ask for forgiveness or renewed hope. We thus behave in ways which cannot be addressed to a machine or a mere set of principles, worthy though those principles might be. When discussing science and religion we need the questioner at least to be open to the idea that this willingness can be a thoroughly rational willingness. It can be as subtle and deep as great poetry, not just shallow and thoughtless like greetings-card doggerel. Its relation to reason can be compared to the attitude we adopt when we recognize other humans as agents with aspirations and their own concerns. That is, it is in tune with reason, not unreason, but it is larger than reason. It is larger in the sense of richer, engaging more not less of us, as the arrival of the Nimrod movement in Elgar’s Enigma Variations is larger than a single melody.

This article is a re-write based on one originally written in 2014 for the OUP blog.