I had an unusual start to my Christmas in 2018 when I was rung up by the Archbishop of Canterbury to ask me if I’d be willing to lead a review of the way the Foreign Office had addressed - or otherwise - the persecution of Christians. It became clear that this was a request from the then Foreign Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, who was very moved by the issue and clearly concerned both about the human stories of Christians caught up in persecution, and worried that his department just wasn’t doing enough about it.

Six hectic months later, almost exactly four years ago, my review was published and the Government (and not just the Foreign Office) accepted my recommendations in full. So how has the UK got on with their implementation?

Before I address that, however, let me deal with two key aspects of my findings and recommendations which are vital for getting inside this issue.

First, I argued that the most effective way to address the persecution of Christians is to guarantee freedom of religion of belief for all – and that includes the right not to believe - and my recommendations were all framed around that conviction. To argue for special pleading for one group over another would be deeply un-Christian. It would also, ironically, expose that group to greater risk, by isolating them and unintentionally portraying them as agents of the West. We must seek freedom of religion of belief for all, without fear or favour.

Second, we need to understand why this is a such a serious issue in today’s world.

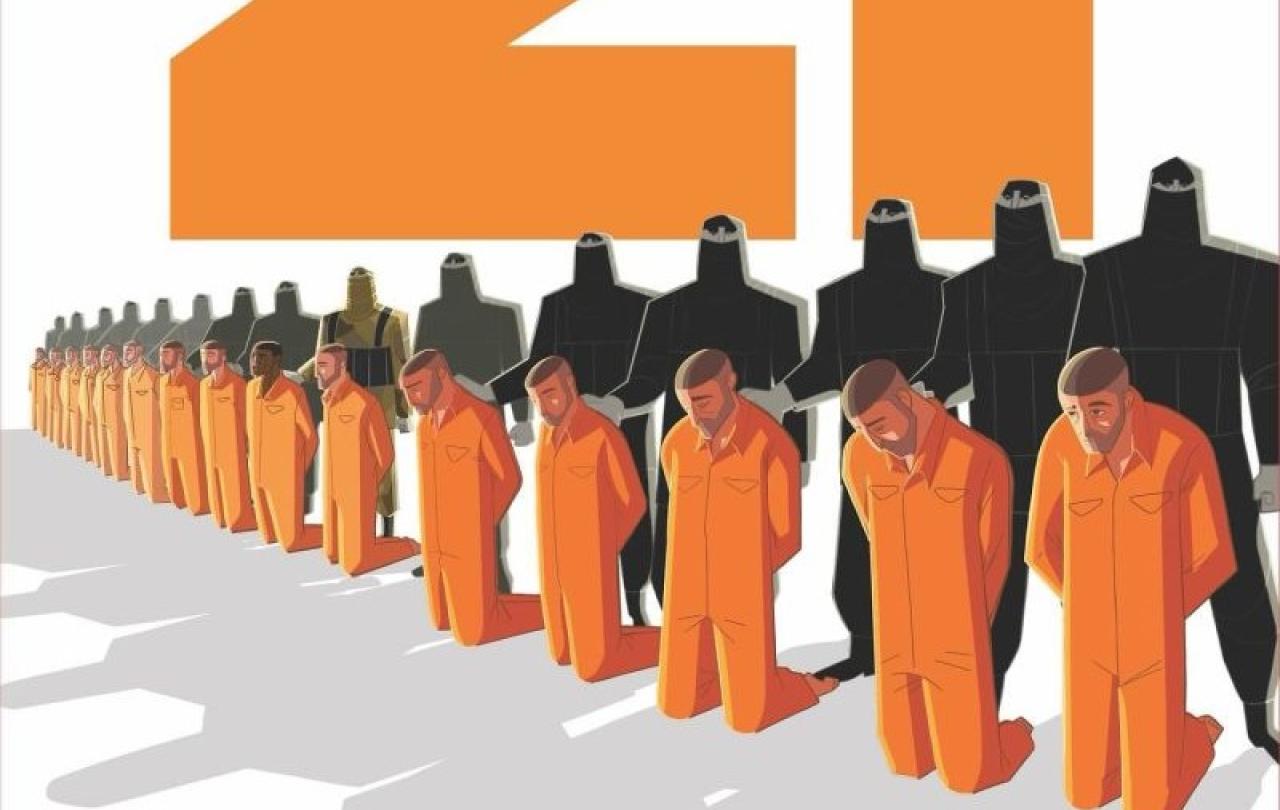

If you lift the stone of persecution and look underneath, what is it that you find? You find authoritarian, totalitarian regimes that are intolerant both of dissent and of minorities; you find aggressive militant nationalism that insists on uniformity; you find religious zealotry and fundamentalism in many different forms that often manifests itself in violence; and in contexts where governments are weak you find gang welfare on an industrial scale driven by drug crime. And you often find those phenomena combined too. In other words, we find massive threats to human flourishing and harmonious communities and ultimately we find in those things significant threats to our own security as well. We can no longer say that this is a sidebar issue of a special interest group. These are huge issues that we face in the world today.

And, the global situation as regards freedom of religion or belief is getting steadily worse, not better, not least in the world’s two most populous countries, China and India. It has certainly worsened significantly since my Review reported. It’s for that reason that the last of my recommendations was that implementation of them all should be independently reviewed three years on from their acceptance. That piece of work was published last summer, just before the UK hosted a major International Ministerial Conference on this issue.

So what did the reviewers conclude? To quote their report:

There has been a positive overall response to the Recommendations, with active steps being taken towards implementing an overwhelming majority of them. However, some of those steps have been taken relatively recently.

I think we can unpack that statement a little. What does ‘There has been a positive overall response to the Recommendations, with active steps being taken towards implementing an overwhelming majority of them’ mean? It means what it says, but it also means that a number of recommendations are in the process of being implemented, but have not yet been completed. And of course it also means that some recommendations remain to be implemented. And what does ‘some of those steps have been taken relatively recently’ mean? Well, it might imply that there was a certain rush of action in the light of the review team’s work being undertaken – all of which underlines the wisdom of including that final recommendation in the first place.

Also of note is the response that the then Foreign Secretary, Liz Truss, made to the reviewers’ work:

We welcome and accept this expert review on progress and in line with the findings, accept their assessment for the need to continue to work to promote and strengthen Freedom of Religion or Belief as a fundamental human right for all…

The independent assessment concludes that the majority of the recommendations are either at an advanced stage of delivery or in the process of being delivered, whilst noting that there is still more to do.

Those skilled at reading statements such as this will point out to you the significance of the Foreign Secretary not just welcoming but accepting the findings. And note too the force of that phrase whilst noting that there is still more to do.

And, as I said, that assessment of progress was published just before the UK hosted the International Ministerial Conference last year. And a great event it was. Through it the UK put down a significant marker as to the significance it attaches to this issue. And we have also taken a leading role in the recently established inter-governmental International Religious Freedom of Belief Alliance, with Fiona Bruce MP, Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Freedom of Religion or Belief currently holding the chair. I take no personal credit for this, but I doubt that either the UK would have hosted the Conference or that Mrs Bruce would have chaired the Alliance had not Jeremy Hunt launched the review – a review which earned him very few political ‘brownie points’ – four and a half years ago.

And yet not all in the garden is rosy. There has been a marked reluctance in some parts of the Foreign Office to recognise the religious dimension in some contexts.

Consider the approach that had been taken to the Middle Belt of Nigeria and the phenomenon of the conflict associated with the Fulani herdsmen. The standard Foreign Office line has been that this is an old conflict between contrasting lifestyles exacerbated by climate change. In other words, the religious dimension is significantly underplayed. A year or so ago the then relevant government minister claimed in a letter to be ‘unaware of substantiated evidence that extremist Islamist ideology is a driver of intercommunal attacks’. I’m afraid that is so completely at odds with the evidence, including that cited in my Review, as to be literally incredible. And, of course, if the Foreign Office claims there is no religious component to the violence they will fail to come up with religiously literate responses to it.

Happily, however more recent statements, in a clear change of tack, have begun to recognise the religious dimension to this unfolding tragedy.

Or take the recent violence in the Indian state of Manipur, with hundreds of churches targeted and destroyed, several killed and thousands displaced. Foreign Office replies to Parliamentary questions about it have been anodyne in the extreme. They remind me of the egregious attitude of the East India Company 250 years ago which protected trade at any price, even in the face of human rights abuses they could otherwise have addressed. Plus ça change.

However even as this article was being written there’s been a further and very significant positive development. Recommendation 20 of my Review called for the UK to sponsor a UN Security Council resolution on this issue. The panel of experts who reviewed implementation last year were not optimistic that it could be achieved. However, on 14 June 2023 the Security Council adopted resolution 2686, a UK-UAE joint resolution on tolerance and religious freedom. Its text addresses growing concern at hate speech and incitement to violence, and calls for action on the persecution of religious and other minorities in conflict. This is the first ever Security Council resolution on this issue, putting it firmly on the international geopolitical table.

In the UK, as elsewhere, we need to recognise that a commitment to freedom of religion or belief is not a ‘nice to have’ in today’s world, additional to the hard world of realpolitik. Not at all it. It touches upon and highlights some key issues in today’s world such as the rise of fundamentalist, nationalistic and authoritarian regimes of all kinds the world over whose treatment of vulnerable minorities is often not short of appalling and whose actions threaten not only the lives and livelihoods of those minorities but also threaten to destabilise international order, increase insecurity, (including food insecurity, as we have seen in this last year) and make it all the harder to address big ticket global issues such as climate change.

Indeed I believe that the wholesale denial of freedom of religion or belief is just one such a big ticket item and I hope and pray we remain sensitised to this issue and appreciate the vital importance of all of us, governments, churches, other faith groups, civil society, and individuals, addressing it with the seriousness and urgency which it undoubtedly requires.