Nestled amidst the tempestuous waters of the North Atlantic Ocean, the islands of St Kilda stand as a testament to isolation unparalleled in the British Isles. Located miles out from the Scottish mainland, the islands form an archipelago that rises defiantly, resembling a fortress of solitude amidst the tumultuous waves.

In 1930, the islanders made a heartfelt plea to be evacuated from their beloved home, as the challenges of survival had become insurmountable. This marked the poignant conclusion of a remarkable two thousand years of human existence on the islands and no permanent community has been established since. Presently, St Kilda stands as a wild and desolate terrain, teeming with a diverse array of wildlife. Amongst the rugged slopes, one can witness the unexpected presence of wild sheep, descendants of the original livestock once cared for by the community. Following the evacuation, the sheep were left to roam freely, adapting to their newfound freedom. Isolated from the outside world for countless centuries, the islands have even given rise to their own unique subspecies of mouse and wren, a testament to the extraordinary resilience of life in this remote haven.

It took me three arduous attempts, spread across consecutive years, to finally set foot on the elusive Hirta, the main island in a cluster of islets and sea stacks known collectively as St Kilda. Access to this remote wilderness is only granted during the warmer months, and my previous endeavours had been thwarted by relentless bouts of stormy weather. However, these failed attempts only served to intensify my determination, turning the eventual arrival into a pilgrimage of sorts, where the sweet taste of success was amplified by the challenges overcome.

Standing at the water's edge, I found myself contemplating the concept of an island as a unique form of solitude, a refuge or retreat, perhaps even a hermitage or prison.

As St Kilda emerged on the horizon, it appeared like a jagged tooth or a mystical axis mundi, a place where the earthly and spiritual realms intersect. Despite its wild and untamed nature, the island is paradoxically dominated by the imposing presence of the Ministry of Defence. Strange listening devices and radars loom over the cliff tops, as if engaged in a silent conversation with the world beyond. Stories of St Kilda often carry an air of romanticism, but the reality of island life was harsh and unforgiving.

As our boat ventured into the circular embrace of St Kilda, a sudden stillness descended upon the waters, transforming the surroundings into an idyllic oasis of tranquillity. The island, formed from the remnants of a volcanic eruption, boasts a natural harbour in the shape of a perfect circle, its walls rising like a majestic amphitheatre to a towering height of 426 metres, equivalent to the Empire State Building, before plunging abruptly into a sheer drop.

The village, consisting of a single street lined with stone cottages known as Black Houses, was the epicentre of island life. Daily existence revolved around the rhythms of fishing, agriculture, and church. Each morning, the island parliament convened to allocate the day's tasks, which often involved harvesting birds, tending to livestock, and repairing nets. Every year, the men of the island would scale the treacherous cliffs with nothing more than homemade ropes to gather the young birds from their precarious nests, while their protective parents swooped and dived in an attempt to thwart such pillaging. Winters were harsh, and the traditions of the church were strict. Missionaries were sent to the island to minister to the faithful, imposing a rigid routine of spiritual disciplines that seemed to serve as both law and religion.

Upon reaching the shore, we were greeted by the island steward, one of only two current inhabitants of the island and resident only in the warmer months. Unless, of course, one counts the Ministry of Defence, whose enigmatic presence permeates every corner of the island. Their satellite dishes and listening posts loom ominously, as if engaged in some clandestine communication with an unseen realm, shattering the illusion of complete wilderness.

Standing at the water's edge, I found myself contemplating the concept of an island as a unique form of solitude, a refuge or retreat, perhaps even a hermitage or prison. It brought to mind the image of Superman in his fortress of solitude or Edmond Dantès, a victim of misfortune, imprisoned and abandoned until the idea of the Count allowed for a rebirth.

But deep down, I knew that this fantasy was far from the brutal reality faced by those who eked out a living on the edge of the world

As a child, I often sought solace on islands during family holidays. There was something about the encircling presence of land surrounded by water that evoked a sense of tranquillity, a sanctuary away from the worries of the world. A sacred space where a weary soul could commune with the divine.

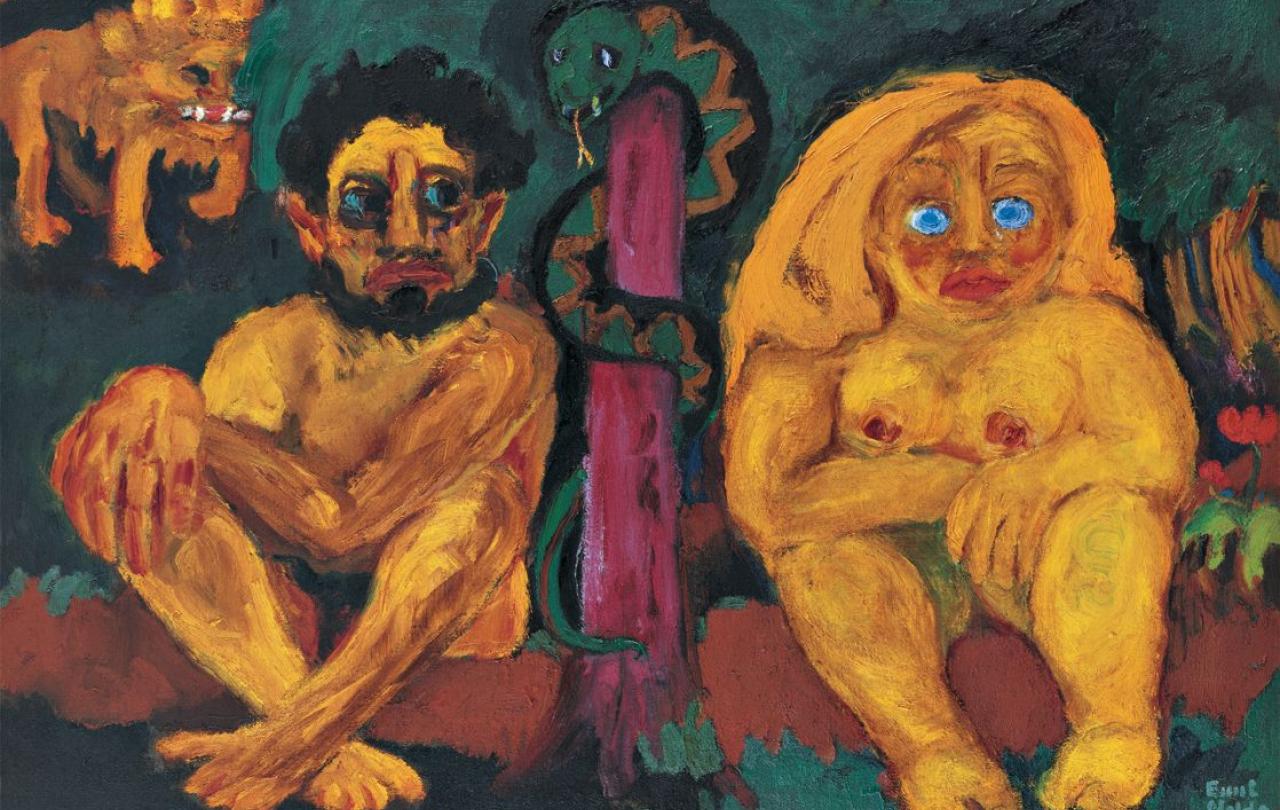

As I ascended the steep walls of Hirta, my camera in hand and sketchbook tucked under my arm, I couldn't help but feel a sense of purpose. I felt like one of those Romantic painters of the previous century who attempted to bring a taste of the natural sublime to the city dwellers, trapped in their concrete jungles and smog-filled air. In that moment, I released mine is not the task of modern-day Romantic painter, venturing into the wilderness to capture moments of awe-inspiring beauty but to chronicle the mundane moments of domestic sublime as witnessed by this landscape through centuries of human inhabitation. The images I captured and the sketches I made now form the basis of new paintings to feature in an upcoming exhibition at An Lanntair gallery in Stornoway.

But as I continued my climb, I couldn't help but question the romantic notions that had fuelled my journey. The landscape itself remained indifferent to my perception of it. It cared not for the grand narratives I projected onto its rugged terrain. It simply existed, unyielding and unapologetic.

And what of St Kilda? Was it truly an idyllic haven, shielded from the political and ecological pollutants of the outside world? Or was it a fortress of solitude, where harsh regimes and a cruel climate ruled? Perhaps it was an oxymoron, embodying both extremes simultaneously.

As our boat sailed away from the island, I found myself pondering the reality of life on St Kilda. What was it truly like to inhabit such a remote place? At times, I allowed my imagination to wander, envisioning a utopia where crime was unheard of, where the absence of policing was a testament to the inherent goodness of humanity. But deep down, I knew that this fantasy was far from the brutal reality faced by those who eked out a living on the edge of the world. Life on St Kilda must have been a constant struggle, a battle against the elements, made bearable only by the flickering hope of a better future.

As I packed away my camera and sketchbook, I couldn't help but feel a sense of gratitude for the opportunity to glimpse into the past, to touch the remnants of a forgotten world. The exhibition I will present in Stornoway will be more than just a collection of art; it will be a tribute to the resilience of the islanders, not just in St Kilda but across the Outer Hebrides in times of hardship, to their ability to find beauty and hope in the harshest of circumstances. And as I prepare to share their story again through painting, I hope that it will serve as a reminder of the fragility and strength of the human spirit, even in the face of isolation and adversity.

Alastair Gordon is an artist based in Edinburgh and London. His new exhibition of paintings opens at An Lanntair in Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, 31 May 2024. The exhibition coincides with a parallel two-person exhibition with Elaine Woo MacGregor opening the same night at Cynthia Corbett Gallery, London.

Sketching St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides