“Why did God create the world?” For Christians, or in fact for anyone, this is one of the most important big questions we almost never ask. Maybe there are good reasons we don’t bother with it. For one, it is dauntingly big. It seems impossible to answer. How would we know what was in God’s mind when God decided to create the world? And didn’t the prophet Isaiah say that God’s thoughts are as far from ours as the heavens are from the earth?

Second, even if we could answer it, the question might not be that important.

Why God created the world seems far removed from our ordinary lives, like the famous philosophical question: “Why is there something rather than nothing?”—interesting to philosophical and theological geeks, but insignificant to the rest of us. Better devote our energies to more consequential and urgent tasks, like improving the lives of the 2.6 billion people who live on $2 a day or less.

Those 2.6 billion poor, are extraordinarily important. I will return to them in a moment, and to how our big question matters for them. But first, let me ask you a question, a personal one. Why do you exist? I am not asking how you came to be born. We all know the basic biology involved. I am asking about the purpose of your life.

Christians, and theists more broadly, have always believed we don’t simply choose the purpose of our lives as it suits us, the way we may choose an outfit for a party. Our purpose is woven into the fabric of our being as God’s creatures. And that takes us back to our question: “Why did God create the world, each one of us included?” You and I are part of the web of creation, and our human purpose, like our flourishing itself, is wrapped up with the purpose of the whole creation. To ask why God created the world is at the same time to ask how to live rightly in our planetary home and what our vocation is in it.

So why did God create the world?

Two books of the Bible, Genesis and the Gospel of John, start with the words ‘In the beginning…’ and then go on to state that God created all things. Neither says right away why. But if you trace the big story they tell that starts with creation, a clear and unified answer emerges: God created the world to be the joint home of God and humans. Here’s how the story goes in each version

The arc of the story that starts at the beginning of the first book of the Bible, closes at the end of the second. God creates and declares creation good, humans sully its goodness, God calls Abraham, God delivers the children of Israel from slavery in Egypt—and all this is to fulfil the one promise: “I will dwell among the Israelites, and I will be their God”). When the glory of the LORD fills the tabernacle at the end of Exodus. God has come to dwell with the people—and led them to the promised land. God’s dwelling in Israel, in the people and in the land, is the capstone of creation.

In John’s Gospel, the very last words Jesus says before he is arrested, condemned, and crucified explain why the world came to be. God creates all things, comes to dwell in Israel, takes on human flesh in Jesus Christ, reveals God’s character, bears human sin and conquers evil with a single overarching purpose: so that the love with which the Father loved the Son before the foundation of the world may be in Jesus’s disciples. In fact, so that the Father and the Son themselves may come to the disciples and make their home with them and in them. Put simply: God created the world to dwell in it.

Once the big stories of the Bible have opened our eyes to see God’s homemaking purpose, it becomes obvious that the Garden of Eden at the beginning and the New Jerusalem at the end are about home. Why did God create the first humans and place them in the garden of Eden? To help the garden flourish as their home. And why did God come to walk in the garden at the time of the cool of the day? Because the garden was meant to be God’s home, too, and not just Adam’s and Eve’s.

The Bible makes the same point at its close. At the very end of Revelation, John of Patmos sees the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven to the renewed earth. To make sure that John doesn’t miss the meaning of what is before his eyes, a loud Voice from God’s throne explains: “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples”. God and the peoples of the earth now have a home together.

The reason why God created the world is not obscure at all: God explained it—more than once. God the creator is a homemaker God.

'We need both wealth and power to have a home. And yet, when they become distorted... they undermine our flourishing and undo our sense of common belonging.’

We can now return to the 2.6 billion impoverished people, many of whom are either homeless or live under conditions that are hardly worthy of the name “home.” Starting with poverty, I will briefly discuss four major forces opposing the original purpose of creation, obstacles to God’s homemaking project.

Let’s think first about the economics of home, specifically about the distribution of wealth (though we could equally well explore the distribution of opportunities). How would you feel about a home in which a child and their mother lived on $2 a day, one sibling lived on $20 a day, another, more privileged sibling on $200 a day, and the father had $2,000 a day for his sole use? (If you do the math you will see that I left out the super-rich from my example; they matter less than we tend to think, and often serve to relieve the bad conscience of people like you and me who belong to the global middle and upper classes.)

Imagine their meal. At one end of the dining room table, two family members in thread-bare clothes with half-full bowls of plain rice and a pitcher of polluted water, while at the other end of the same table the father and the other sibling, dressed in the latest fashion, enjoy culinary masterpieces and exquisite wine? If that happened in your neighbor’s home, my guess is you’d be scandalized. As the story Jesus told about the Rich man and Lazarus attests, God would be scandalized as well.

And yet, you and I live in just such a home, our single planetary home. Even if you are at a loss about what exactly to do about the issue, as I am, discomfort with how far we are from God’s purpose for the world is what we should feel.

The politics of home closely tracks its economics. The malnourished and shabbily clad group at the one end of the table will cast longing looks toward the other side of the table. How could you blame them for wanting to partake of that sumptuous meal? As to the feasters, if they even dignify the other side of the table with their attention at all, it will be with a sense of their own superiority—and to ensure that the poor are kept at a distance. For the proximity of the ‘tribe of Lazarus’ could endanger their superior standing and the benefits of their privilege.

Eventually, some kind of wall would go up and security apparatus would be put in place. What was a single home would be divided. Lazarus, perhaps with bitterness and anger simmering in his soul, would end up in some make-shift abode. The rich man would build himself his fortress, a testimony not just to his wealth but to his fear as well. Both would be homeless, though each in a different way—one locked up in the gilded prison of his luxury and false superiority, the other mired in a life of languishing and precarity. Fundamentally, the two are brothers (Abraham’s children, in Jesus’s story). God created each. God meant for both to live in a single home.

From the dawn of history until the present day, wealth and power have been thwarting God’s homemaking purpose. More specifically, our inordinate love for wealth and misuse of power have done so. For we need both wealth and power to have a home; indeed, we could not even exist at all without some form of wealth and power. And yet, when they become distorted, when they acquire the monstrous features of what the Bible calls Mammon and Leviathan, they undermine our flourishing and undo our sense of common belonging.

The monsters in our home

Mammon and Leviathan are ancient foes of God’s home. It is important to be on the lookout for specifically modern foes of God’s home as well. I will note here only two. Being modern, they also have modern - sounding names: escalation and reification. The fancy names notwithstanding, we experience these un-homing forces every day—and they, too, are monsters like Mammon and Leviathan.

Let’s start with escalation. To survive in modern societies, you have to live the way you ride a bicycle: moving forward. The moment you stop, you fall. And the thing is, it’s not enough just to move at whatever pace suits you or you are able. You are in a race whether you want to be or not, and you have to keep moving faster and faster. That’s escalation. Call this monster Cursus, the racer. He distorts our experience of both time and space.

'We are always running behind, always running.'

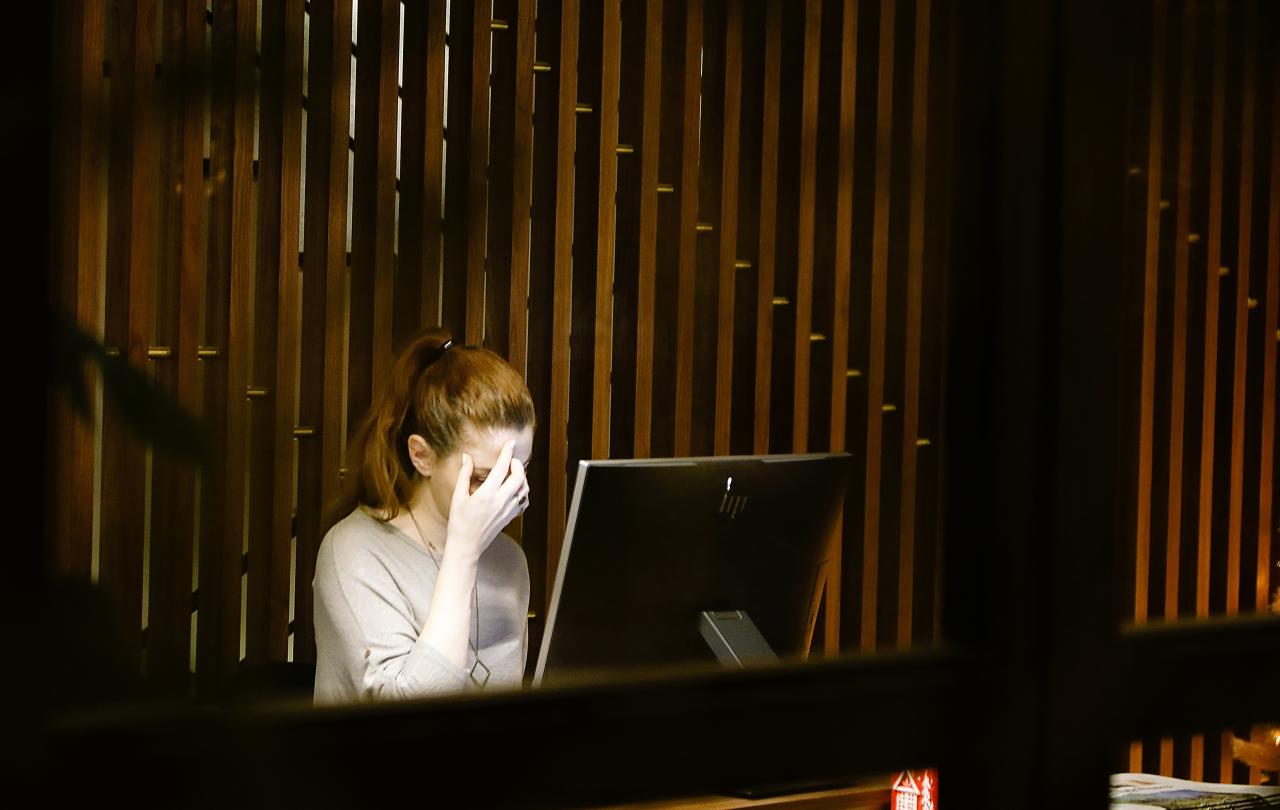

First, the pace of life is accelerating. We never have enough time. Describing the phenomenon, sociologist Hartmut Rosa writes: ‘“Amidst monetary and technological affluence, [citizens of modern societies] are close to temporal insolvency.’” For short, we are always running behind, always running. Whether we are on the poor or rich end of the table, we mostly rush through our meals, worrying about what we have left undone, catching up on the news, multitasking. Meals, like the rest of our lives, are just the speedy steps of a hamster whose wheel is spinning faster and faster. And a hamster wheel can never be a home for us humans.

Second, the scope of our activities is expanding. When I was a student, we used to joke about the president of our college. What’s the difference between God and Dr. Kuzmič? God is everywhere and Dr. Kuzmič is everywhere except here. Students today could not tell that joke without becoming themselves the butt of it. With a smart-phone in their hand they, too, are everywhere except here! “Always somewhere else!” means, “Never really at home!”

Home needs time, and home needs presence. The logic of escalation, the monster Cursus, makes both hard to come by. The story that it keeps telling us is this: Where I am and what I do, who I am and what I have, are never good enough. The consequence? With Cursus running our lives, there is no time when I feel at home and no place where I am at home.

'To a person with a tool, all things become manipulable objects.'

Now to reification, the second modern monster, whom I will call Medusa, one who turns things into stones. Another term for reification is ‘thingification'—everything that surrounds us, all God’s creatures, turned into cold, lifeless things! This dynamic is all around us. It’s there in the sciences, which tend to treat all entities as things, part of the network of mathematically calculable causal relations. Modern technology does the same. To a person with a hammer, all things look like a nail, the saying goes. To a person with a tool, all things become manipulable objects. Modern medicine is a case in point. It is very successful, but that is in part because it tends to treat human bodies as 'machines' to be fixed.

For a smaller-scale example of Medusa’s reifying work, return with me to Lazarus at one end of the table and the rich man at the other. Lazarus sits on a scratched-up wobbly plastic chair fished out of a dumpster. It is a mere replaceable thing for him; it serves its purpose, although rather badly. It is not an “old friend” with which he resonates so that when he sits on it he feels at one with it, at home with his chair. The rich man sits in his armchair as a king on his throne, but for him, too, the chair is not an old friend. It’s a thing whose essential purpose is to underscore his superiority. If anyone at the table had a better chair, he’d discard this one and go buy himself an even better one. When people and things matter to us only as means but not in their own right, we don’t have a home.

'We humans can be what we are created to be only together.'

So we have our answer to that very big question: Why did God create the world?

God created the world so that it might be God’s home and ours. But we also have these four home-destroying monsters: Mammon, Leviathan, Cursus, and Medusa.

The conflict between God’s homemaking and these monsters is the site of both the Christian and human calling. Jesus was God in the world on the mission of planetary homemaking. He gave the disciples his Spirit so that they would continue his mission and do their part in helping make the world into God’s home and ours. Why? Because we humans can be what we are created to be only together and when each of us becomes a nodal point of genuinely home-like relations. Granted, we can’t ever make the world into God’s home. We can’t even make it fully into our home. But we can live in more homelike ways. We can take the time to build resonant relationships with people and places. And we can work to heal the fractures caused by those unhoming forces. We can struggle against homelessness in our cities, or work for more participatory politics and equitable economics. We can open ourselves to God’s transformative presence. We ourselves can be homes of God and home-makers with God while we await the coming home of God.

And that is why you need to know why God created the world.