I had an empty couple of minutes to play with; so, mostly due to muscle memory, I found myself opening my Instagram app. Habitually, I do this multiple times a day, and mostly to no profound avail. But this one day, something caught my eye and sent me down a spiral of curiosity (and judging by how astronomically viral it went, it seems I was not spiralling alone).

It was footage of Jacob Collier performing in Rome. Jacob is a singer, songwriter, jazz instrumentalist and general music prodigy. But that’s not the most captivating thing about him. The Collier phenomena has erupted because of the way he turns his audience of strangers into a perfectly tuned, beautifully united, choir. And this particular night in Rome, he managed to steer this audience to sing beyond the major scale and onto the far more complex chromatic scale, something he has been working towards for years.

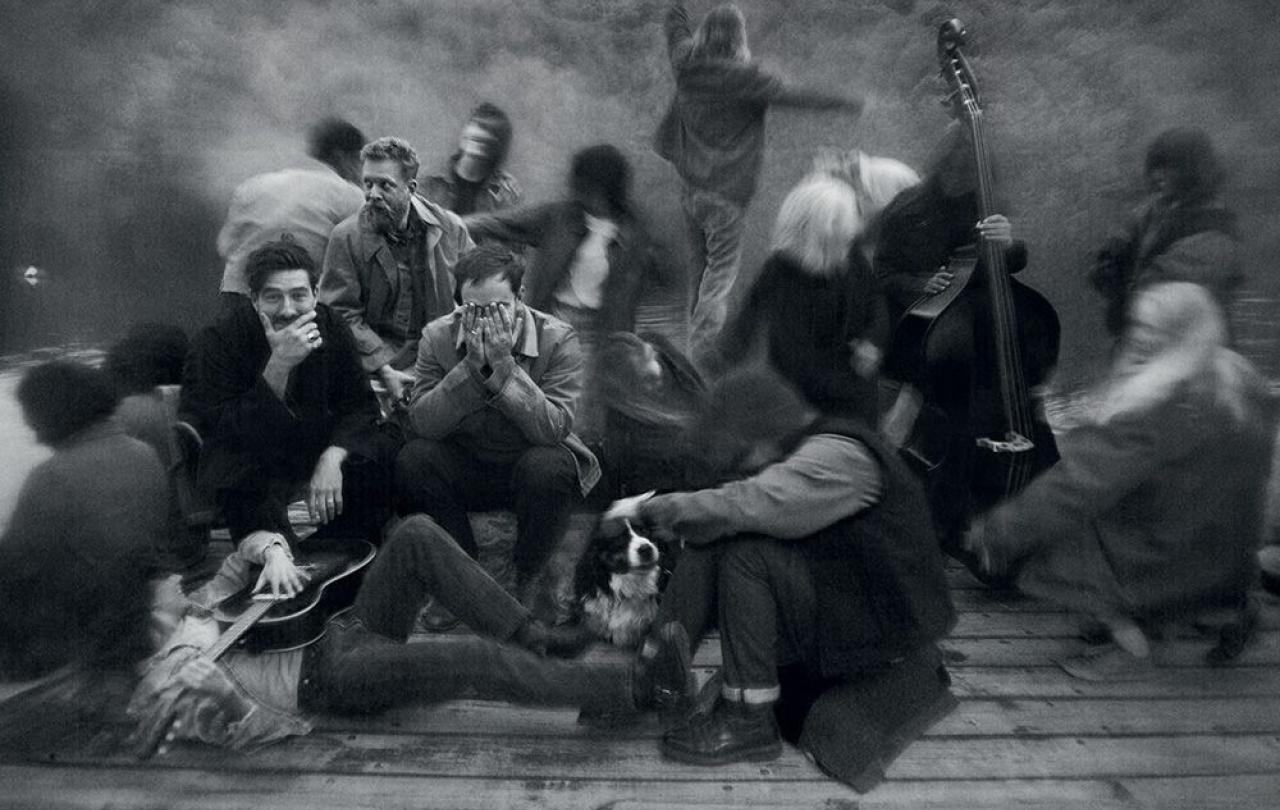

The most striking thing about this minute-long clip is not the beautifully raw sound (although, it really is something to behold), but what this sound is communicating - a tangible sense of belonging.

Watch Jacob Collier in Rome

Our need to belong

We each know how it feels to belong, and we are also acutely aware of the inverse, how it feels when a sense of belonging is lacking, and feelings of isolation creep in and make themselves at home in its absence. But for the sake of clarity, perhaps a working definition would be helpful at this point, and for that, I turn to the Psychology Dictionary. The PD defines ‘belonging’ as ‘a feeling of being taken in and accepted as part of a group, thus, fostering a sense of belonging. It also relates to being approved of and accepted by society in general. Also called belongingness.’

The notion of ‘belonging,’ or ‘belongingness,’ has been well studied. And still, its intrinsic power is staggering to consider.

According to research published by the Australian Journal of Psychology, belonging is a universal and fundamental human need, one that ‘may just be as important as food, shelter, and physical safety’. So intrinsic is it, that the lack of belonging, resulting in acute loneliness, is attributed to a 26% increase in the risk of premature mortality. This has led the World Health Organisation to officially recognise isolation as a determinant of health, placing it in the same category as smoking, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption.

Further research suggests that our brains perceive, and subsequently react to, social pain in the same way they are designed to react to physical pain. Releasing opioids and other instinctive painkillers when encountering a lack of belonging, our brains are detecting literal pain within us. As humans, we are susceptible to suffering social injuries, and it seems that the subconscious parts of our brains take those injuries much more seriously than their conscious counterparts.

The necessity of belonging is woven into our make-up.

Subsequently, when we speak of a person’s need to belong, we’re speaking of a need that has significant mental, emotional, spiritual, behavioural, and physical repercussions; a need that is intersectional, if you will. It is a central construct at the core of our humanity and a defining variable in how we perceive reality.

It could be suggested, considering all of this, that human beings were simply made to belong. The necessity of belonging is woven into our make-up.

Surrounded by people versus belonging with people

Over the final scene of the 2009 film World’s Greatest Dad, Robin Williams’ voice delivers a line that is so profound it lingers in your mind long after the end-credits have finished rolling. He says ‘I used to think the worst thing in life would be to end up all alone. It’s not. The worst thing in life is to end up with people who make you feel alone.’

There’s a staggering wisdom in that.

Namely, that belonging is not the inevitable outcome of simply getting people into one room. That’s the difference between the Collier concert - where the audience are truly belonging to each other, if only for an evening - and the coffee shop where I’m sitting right now, filled with people using laptops and headphones as a form of defence against the threat of small talk. Each of us belonging only to ourselves.

If it were the case that proximity equated to belonging, urbanization and the subsequent squeezing of populations into close quarters would have surely deterred the epidemic of loneliness that the West currently finds itself in. And yet, it is not uncommon for ‘neighbour’ and ‘stranger’ to be identities that co-exist. And what about the role of social media? Access to one another has never been so readily available. The world has never been so small, and its population so ‘close.’ And yet, what social media so often provides is the affirmation and amplification of feelings of isolation.

No. Proximity alone is not the answer.

Will Van Der Hart writes that ‘People don’t just want to be with other people they want to belong with them’.

The tuning fork

Christianity has a lot to say on the subject of belonging/belongingness.

The anonymous author of the creation literature (the chapters which act as the start-line for the Biblical narrative) notes how the only thing that was unsatisfactory about our freshly created world was the initial isolation of humanity. Such solitude was at odds with the blueprint for human flourishing and defied our design as intrinsically relational beings. The Christian faith therefore offers an explanation to humanity’s fundamental need to belong, It presents a spiritual why behind the afore-mentioned neurological findings.

The biblical narratives, the psychological research – they are united (if you pardon the pun) in their assessment of the human condition. Namely, that belonging is simply a non-negotiable, it’s buried inside our biology.

So, perhaps it’s no wonder Jacob Collier has caught the world’s attention, he’s providing a simple soundtrack to one of our most engrained needs. It seems that what has long been communicated through ancient spiritual texts and more recently affirmed through endless psychological theories, can also be communicated with a simple harmonious sound.

To watch that clip is to watch thousands of strangers belong: belong to the room, belong to the moment, belong to the sound.

In 1948, author and theologian, A.W Tozer pondered the nature of unity and human connection. He asked, ‘has it ever occurred to you that one hundred pianos all tuned to the same fork are automatically tuned to each other?’

If ever we were looking for an answer to this profound question, we need look no further than Jacob Collier’s audience and their sound of belonging.