Taking inspiration from human attention has made AI vastly more powerful. Can this focus our minds on why attention really matters?

Artificial intelligence has been developing at a dizzying rate. Chatbots like ChatGPT and Copilot can automate everyday tasks and can effortlessly summarise information. Photorealistic images and videos can be generated from a couple of words and medical AI promises to revolutionise both drug discovery and healthcare. The technology (or at least the hype around it) gives an impression of boundless acceleration.

So far, 2025 has been the year AI has become a real big-ticket political item. The new Trump administration has promised half a trillion dollars for AI infrastructure and UK prime minister Keir Starmer plans to ‘turbocharge’ AI in the UK. Predictions of our future with this new technology range from doom-laden apocalypse to techno-utopian superabundance. The only certainty is that it will lead to dramatic personal and social change.

This technological impact feels even more dramatic given the relative simplicity of its components. Huge volumes of text, image and videos are converted into vast arrays of numbers. These grids are then pushed through repeated processes of addition, multiplication and comparison. As more data is fed into this process, the numbers (or weights) in the system are updated and the AI ‘learns’ from the data. With enough data, meaningful relationships between words are internalised and the model becomes capable of generating useful answers to questions.

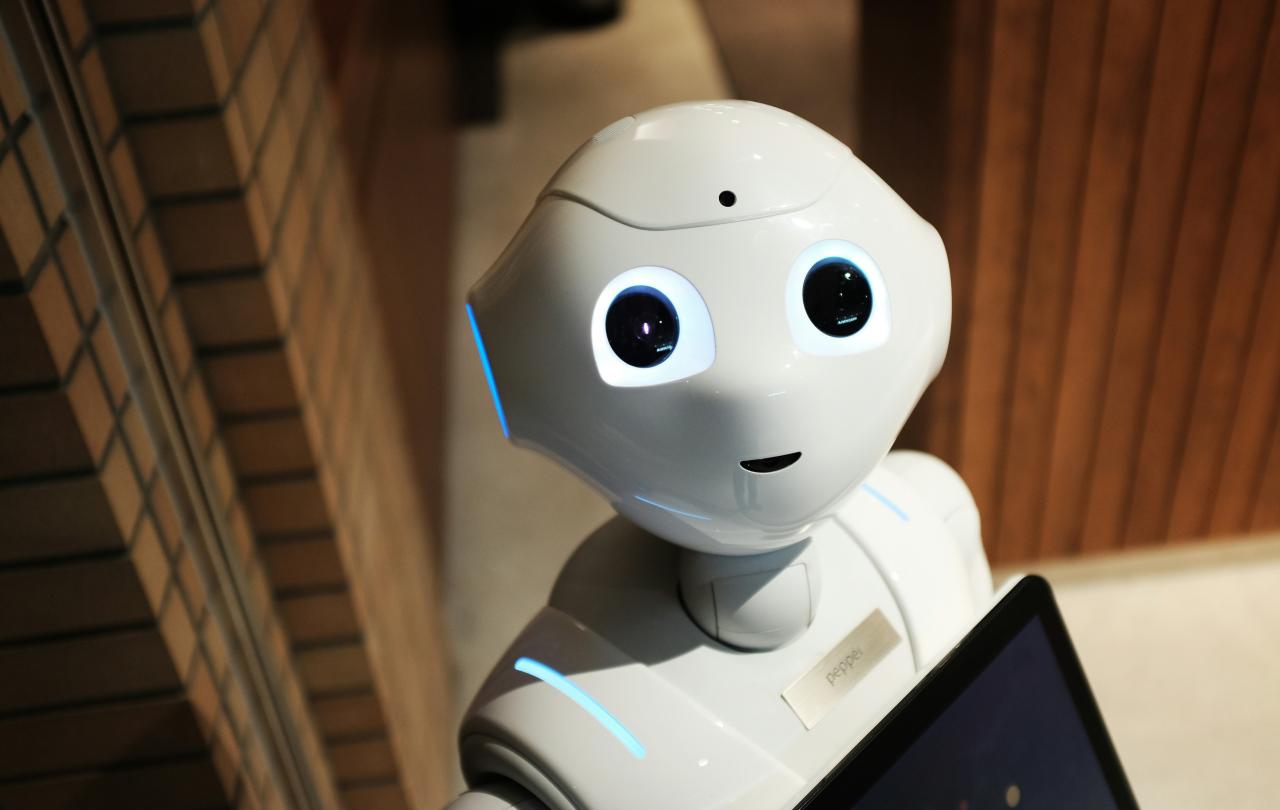

So why have these algorithms become so much more powerful over the past few years? One major driver has been to take inspiration from human attention. An ‘attention mechanism’ allows very distant parts of texts or images to be associated together. This means that when processing a passage of conversation in a novel, the system is able to take cues on the mood of the characters from earlier in the chapter. This ability to attend to the broader context of the text has allowed the success of the current wave of ‘large language models’ or ‘generative AI’. In fact, these models with the technical name ‘Transformer’ were developed by removing other features and concentrating only on the attention mechanisms. This was first published in the memorably named ‘Attention is All You Need’ paper written by scientists working at Google in 2017.

If you’re wondering whether this machine replication of human attention has much to do with the real thing, you might be right to be sceptical. That said, this attention-imitating technology has profound effects on how we attend to the world. On the one hand, it has shown the ability to focus and amplify our attention, but on the other, to distract and suffocate it.

Attention is a moral act, directed towards care for others.

A radiologist acts with professional care for her patients. Armed with a lifetime of knowledge and expertise, she diligently checks scans for evidence of malignant tumours. Using new AI tools can amplify her expertise and attention. These can automatically detect suspicious patterns in the image including very fine detail that a human eye could miss. These additional pairs of eyes can free her professional attention to other aspects of the scan or other aspects of the job.

Meanwhile, a government acts with obligations to keep its spending down. It decides to automate welfare claim handling using a “state of the art” AI system. The system flags more claimants as being overpaid than the human employees used to. The politicians and senior bureaucrats congratulate themselves on the system’s efficiency and they resolve to extend it to other types of payments. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands are being forced to pay non-existent debts. With echoes of the British Post Office Horizon Scandal, the 2017-2020 the Australian Robo-debt scandal was due to flaws in the algorithm used to calculate the debts. To have a properly functioning welfare safety net, there needs to be public scrutiny, and a misplaced deference to machines and algorithms suffocated the attention that was needed.

These examples illustrate the interplay between AI and our attention, but they also show that human attention has a broader meaning than just being the efficient channelling of information. In both cases, attention is a moral act, directed towards care for others. There are many other ways algorithms interact with our attention – how social media is optimised to keep us scrolling, how chatbots are being touted as a solution to loneliness among the elderly, but also how translation apps help break language barriers.

Algorithms are not the first thing to get in the way of our attention, and keeping our attention on the right things has always been a problem. One of the best stories about attention and noticing other people is Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan. A man lies badly beaten on the side of the road after a robbery. Several respectable people walk past without attending to the man. A stranger stops. His people and the injured man’s people are bitter enemies. Despite this, he generously attends to the wounded stranger. He risks the danger of stopping – perhaps the injured man will attack him? He then tends the man’s wounds and uses his money to pay for an indefinite stay in a hotel.

This is the true model of attention. Risky, loving “noticing” which is action as much as intellect. A model of attention better than even the best neuroscientist or programmer could come up with, one modelled by God himself. In this story, the stranger, the Good Samaritan, is Jesus, and we all sit wounded and in need of attention.

But not only this, we are born to imitate the Good Samaritan’s attention to others. Just as we can receive God’s love, we can also attend to the needs of others. This mirrors our relationship to artificial intelligence, just as our AI toys are conduits of our attention, we can be conduits of God’s perfect loving attention. This is what our attention is really for, and if we remember this while being prudent about the dangers of technology, then we might succeed in elevating our attention-inspired tools to make AI an amplifier of real attention.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief