Dietrich Bonhoeffer famously made a decision to return to Germany before the outbreak of the Second World War. The year was 1938, and he was visiting America for a second time. Instead of taking a theology teaching position in New York that would’ve kept him above the fray of a deteriorating social world in Germany, Bonhoeffer’s sense of spiritual responsibility drove him to solidarity with the German situation.

I’ve thought about Bonhoeffer a lot these last few months as our family is making a transition back to the States during an election year. Not because I’d ever directly compare our move with Bonhoeffer’s. But because I’m anticipating the “shock” of returning to a deteriorating social world. Unlike him, our decision to return is far more modest and expedient. Still, we’re often asked by our friends here in Scotland, “why go back?”

My immediate answer is straightforward and entirely different than Bonhoeffer: we did what we came here to do. Our visas are up; I’m defending my PhD this month. But behind these questions of expediency, I do feel the weight of an existential question, one directed towards myself as much as it is towards America.

And that question is “who is going back?” Because after three years, America has changed to us as we’ve changed ourselves.

The persecution confronting white Christians in America is the soft persecution of opulence diffused in the ordinary.

With that change comes new choices and new questions that didn’t confront us years ago. Returning to America has us asking questions like, how do you talk to your school-aged kids about active shooter drills in their new school? How will we navigate the racialized social scripts that pervade not just American communities, but also American churches? How will we re-enter a job market that ties production to basic health care?

We’re bracing for the shock of going back to America. It will be more difficult than leaving ever was. Not just because we’ve changed, but also that the American situation has grown more extreme while paradoxically denying that change.

We’ve discovered that if American Christians are persecuted at all, it’s not from President Biden’s “corrupt regime” seeking to jail Trump or secure power through another “rigged election.” No, the persecution confronting white Christians in America is the soft persecution of opulence diffused in the ordinary.

As an expat returning to America, I wonder if this exhausted majority is, in fact, asleep.

Perspective changes everything. The outsider’s view of America careening towards a crisis of democracy and a social fabric rent at the seams isn’t felt as much by those who live within its social world, whose experience of the mundane obscures the poly-crisis pressing our social fabric at the seams. How did we get here?

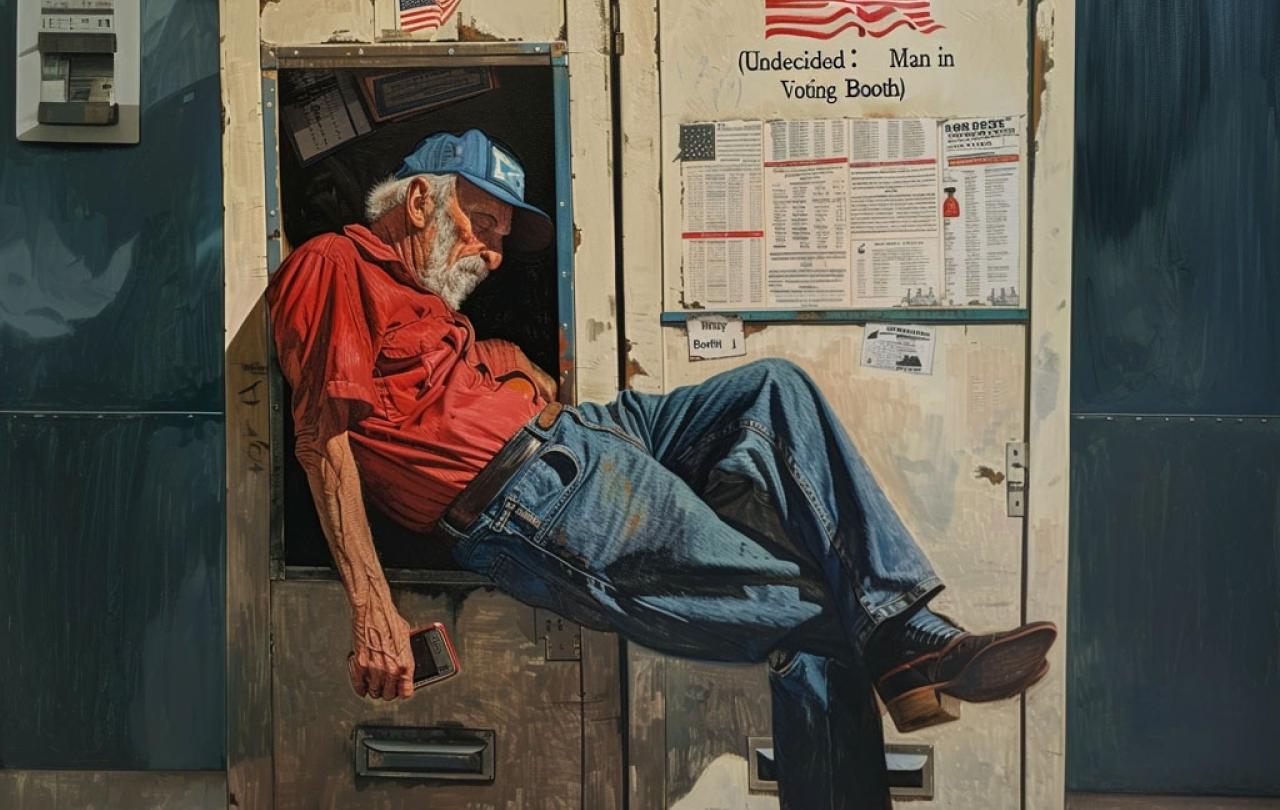

Researchers discovered an interesting demographic cohort in American life, you might have heard of it. It’s called the “exhausted majority.” It refers to an ideological diverse cohort at the center of American life that has all but disengaged politically. Researchers began to talk about this “exhausted majority” in 2018, before the pandemic, before a less-than-peaceful transfer of democratic power. The hope was, then, that this “exhausted majority” might be mobilized to fend off polarization and extremism. As an expat returning to America, I wonder if this exhausted majority is, in fact, asleep.

What has become of this exhausted majority? In the wake of 2020, America underwent significant backlash and retrenchment. This affected churches, too. Friends who are pastors tell me churches in their communities have “re-sorted” along partisan lines. One pastor suggested the election might not divide churches this time, as much as partisan-determined churches might contribute to social division. Polarization has worked its way from the outer edges of American life to the very center. It does this work silently, mediated by our reliance on algorithms, a life conformed to and captured by digital architecture.

There’s an element of surprise here, at least for us as we return. Because what we experienced as the collapse of our social world in white evangelicalism—a world that we no longer are at home in— I’ve found is still very much active, very much automated—like survival reflexes—still providing an artificial coherence and plausible deniability amidst a deteriorating social situation.

This retrenchment and backlash creates a dangerous condition: an undertow. For so many, life goes on as normal on the surface, while democratic institutions are pulled apart beneath. America is caught in a rip current, but asleep on the surface. This undertow partly explains, at least to me, why all the talk of “the crisis of democracy” doesn’t register with many Americans.

A recent survey found that more than half of Americans haven’t heard the term “Christian Nationalism”—in spite of a flurry of academic and popular discourses on the term, often at the center of “crisis of democracy” rhetoric.

The fact is, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and it didn’t fall in a day, either. The Senate handing over power to Caesar one day didn’t do much to alter the mundane early morning routine of bread makers in Rome the next day. Tyranny dawns, but the ordinary continues. The routine of the mundane and ordinary, of bread and circuses, makes talk of a democratic collapse seem just another political game, a distraction from all the amusement that Neil Postman observed might be our death.

As we return to America, reflecting on who we’ve become and the responsibility of faith, I’ve found myself considering the difference between being fated and being holy.

Fate confronts us as necessity. The holy confronts us as something other. And this “other”—at least for Bonhoeffer—was the freedom of God. And I can think of no better prayer for the church in America in the coming years to maintain in ourselves the crucial distinction between fatedness and holiness. To not confuse the expediency of partisan games with the responsibility made visible in the light of the central claim of Christian faith in the body of Jesus Christ. The Crucified One, not the fate of Western Civilization, determines what it is to be the ekklesia, the “called out” community, both free and responsible, never fated.