Children will always tell you what they think about a piece of art.

London recently hosted the Freize annual art fair. It’s where galleries sell contemporary art and old masters. Alongside the ticketed fair, there was a free public art installation of sculpture in Regent’s Park.

The “public-ness” of the art is crucial here. While the major art fairs around the world primarily attract those “in-the-know” - the experienced gallerists, art journalists and wealthy buyers - the installation in the park attracts a wider range of Londoners. They are the art curious who aren’t committed enough to buy a ticket, the young families looking for free Saturday activities, and those who wandered into the park unplanned, perhaps on their way to a picnic or frisbee toss, all come to grapple with the art before them.

Stood in front of one sculpture, comprising tree bark branches rising into the mythical face of a sea creature, a child remarked “that’s too scary” to her mother. Elsewhere in the park, children ran up to the works, giving bronze pieces anything from a playful tap to an aggressive bang to hear what sound it would make. They wandered up to brightly coloured pieces, quickly walked past things they didn’t like, and always spoke their mind. “That’s too scary.”

The brutal honesty of children is not a contemporary phenomenon formed by permissive parenting self-help books or new-age educational theories. Even in ancient times, children were known for their lack of pretence.

In the Bible’s book of Matthew, Jesus was approached by a group of parents and their rambunctious children. When his disciples tried to rebuke them, Jesus said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.”

It is the same lack of pretence that causes children to run up to sculptures and whack them to see what noise it makes and that caused the children to run up to Jesus. Children aren’t scared to “miss the point,” they look for answers and vocalise their confusion to anyone willing to listen.

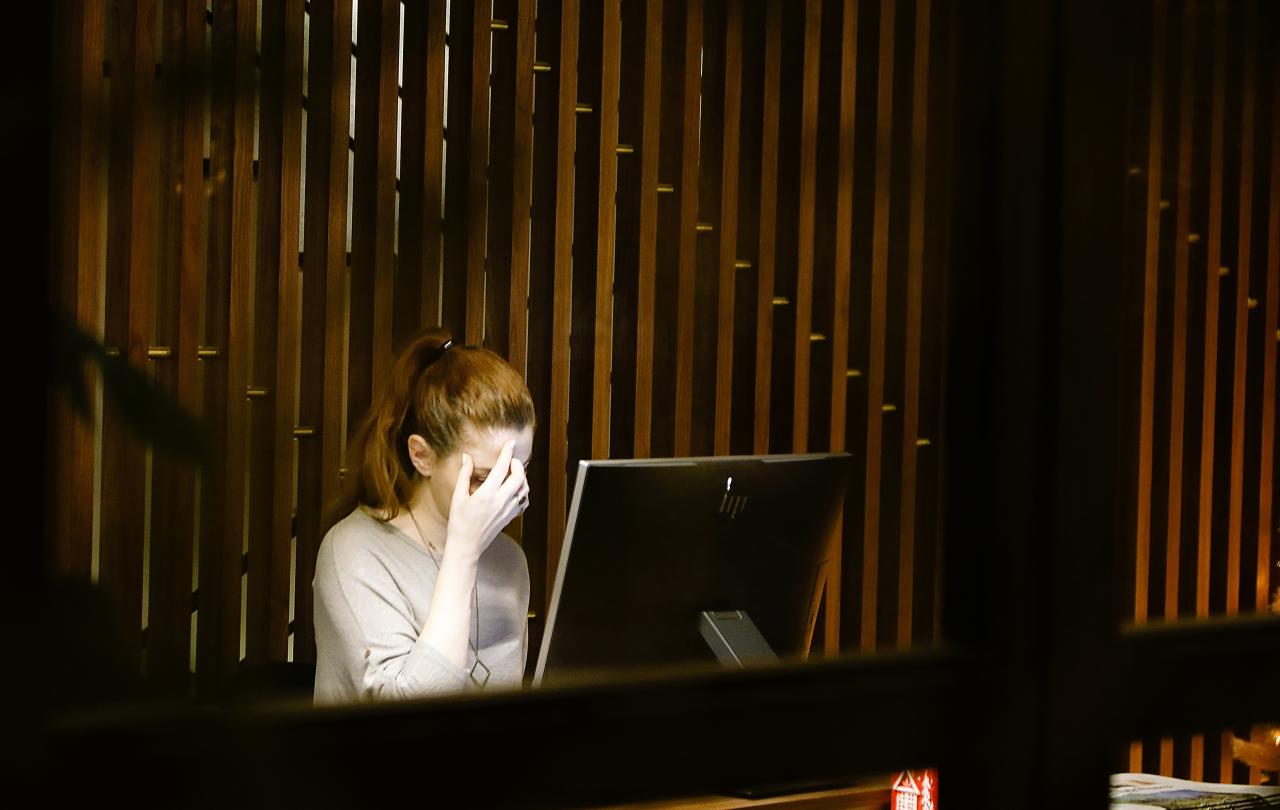

Anyone who walks into one of London’s typical “white cube” galleries can sense a real exclusivity in the art world. Even those on the inside can fear taking a dislike to a piece they’re meant to like. Or worse, not understanding a piece everyone is speaking about. For some, religion can feel similar.

But God doesn’t call us to have the right opinions. Creation is not a test to be answered correctly or an art investment to weigh the risks of. The Christian view of the world is far closer to children wandering along that Regent’s Park sculpture trail. We are called to explore, to know what we don’t know and to try, in humility, to look for the answers. The end of our lives won’t bring a group of high-minded gallerists checking to see if we have informed opinions or good connections. It will bring a God excited to show us the work of his hands, welcoming all in to share in its glory.