Nicola Olyslagers is an Australian high jumper who recently won silver at the Paris Olympics. Gearing herself up for one of her final jumps, she lifted her hands and eyes to the heavens at which point the BBC commentator said: ‘and so, she looks to the gods for help as she prepares to jump’.

All very dramatic. Except that is exactly what she was not doing.

Olyslagers is a devout Christian. She found her faith aged 16, and regularly speaks of it in public. Her pre-jump routine was not a prayer to the gods of the pagan pantheon, an appeal for a slice of luck or good fortune, but a prayer to the God of Jesus – a commentator who had done their homework might have been expected to know that.

In such a public display of devotion, she is far from alone. A feature of this Olympics is the number of athletes who have worn their faith on their sleeves, from Adam Peaty to Gabriel Medina, in the most famous surfing photograph of the games. Every night you see someone thanking God, crossing themselves, advertising their faith – not mainly as a plea for victory, but as Ashley Null points out elsewhere on Seen & Unseen as a way of handling the ups and downs of elite sport.

When you place these public professions of Christian faith next to the row over the opening ceremony, it raises an interesting question. During that ceremony, Christians around the world were upset at what looked like a parody of the Last Supper. Olympics organisers then claimed that the offending scene was not intended to mock the heart of Christian worship but was a reference to Dionysius and the feast of the pagan gods, connecting the modern Olympics with its roots in the pagan world of the classical period.

If it was a reference to Dionysian pagan feasting, the opening ceremony was perhaps a more telling sign of the direction of our culture than we might think, and one that might cause Christians even more concern than a second-rate mockery of the Last Supper. Because it clarifies a choice that our culture might face as our era proceeds.

****

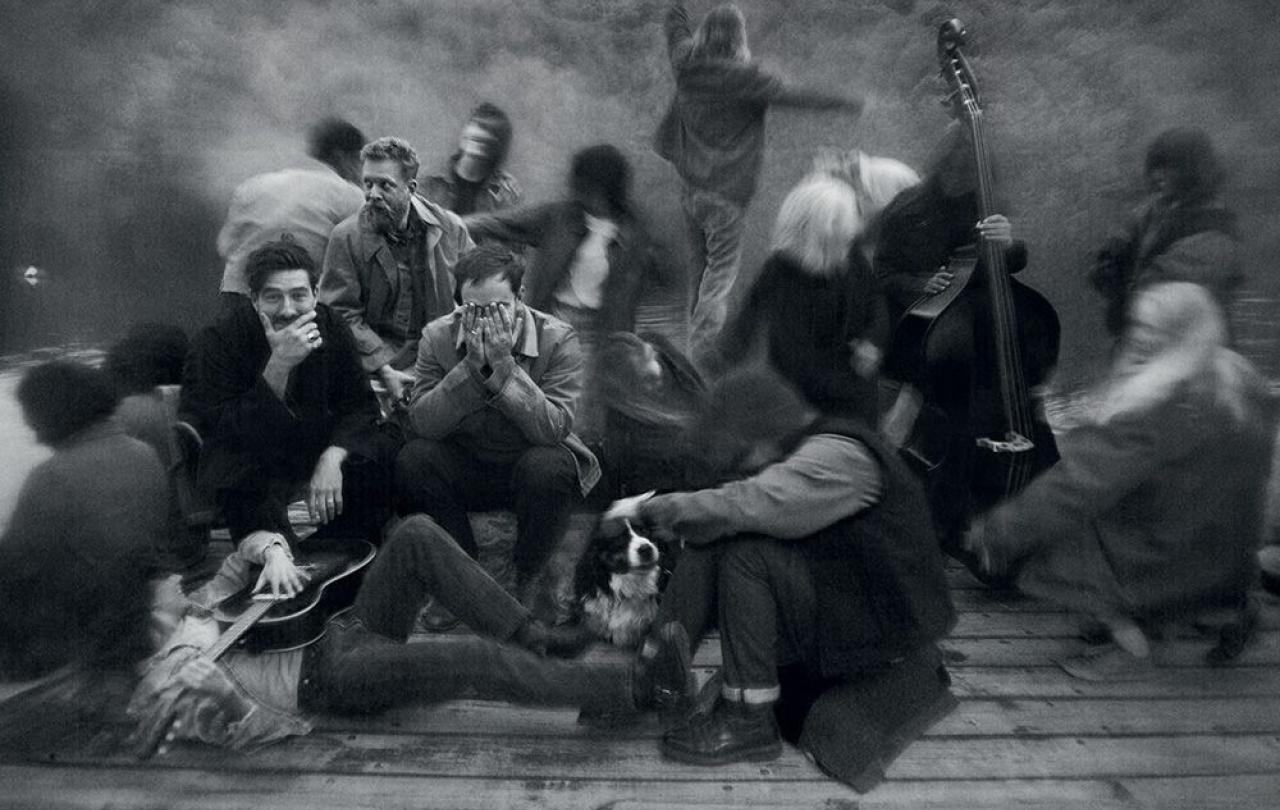

Gabriel Medina celebrates his surfing gold medal.

In 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, T.S. Eliot gave a series of lectures in the refined setting of Corpus Christi College Cambridge, which were eventually published as The Idea of a Christian Society. In it, he laid out a stark prognosis:

“The choice before us is between the formation of a new Christian culture, and the acceptance of a pagan one."

Eliot thought that his society was neither fully Christian, nor fully pagan, but ‘neutral’. Yet he feared that could not last long. Such ‘political liberalism’ was in danger of fostering its own demise by an indiscriminate refusal to make moral value judgments and decide between versions of the good. As he watched the rise of fascism in Europe, which stood on the verge of the most destructive war in its history so far, he made a significant claim: that the only alternative to what he saw as a pagan totalitarianism was a Christian society.

Closer to our times, a similar thought has occurred to other influential figures. The feminist writer Louise Perry recently mused over the idea that our society is re-paganising, citing the moral conundrum over modern abortion. Despite not being a practising Christian, she sees abortion bearing uncomfortable similarities to pagan infanticide, a sign that we are heading back to a moral scheme with a strong likeness to pagan valuations of human life. The Jewish feminist writer Naomi Wolf has done the same, in an extraordinary essay. Despite a tendency to veer into conspiracy theories too easily, she makes a compelling case that as the Jewish-Christian ethos that underpinned western society has receded, what has emerged is not a benign neutrality, but dark powers that used to lurk in the background of Old Testament religion:

“the sheer amoral power of Baal, the destructive force of Moloch, the unrestrained seductiveness and sexual licentiousness of Astarte or Ashera — those are the primal forces that do indeed seem to me to have returned… or at least the energies that they represent — moral power-over; death-worship; antagonism to the sexual orderliness of the intact family and faithful relationships — seem to have ‘returned,’ without restraint.”

The Nazism to which Eliot referred, as we now know, was a dead end - literally. We console ourselves today with the thought that we have left such extremes behind, that the idolatries of fascism and communism were defeated in 1945 and 1989 respectively, and that we now inherit a secular liberal democratic space which is happily neutral and keeps the peace between different claims to truth – an advance on either paganism or Christianity.

That may be true, but as Rowan Williams pointed out, there is a difference between ‘procedural secularism’ – a non-dogmatic role for the state in helping keep equilibrium in a society where there is no common agreement on truth, and ‘programmatic secularism’, which imposes a distinct set of values on society which tend to inhibit religious expression and denies anyone the right to claim their religious perspective is ultimately true.

The makers of the Olympic opening ceremony, without a trace of irony, justified their creation by saying that it was celebrating French Republican ideas of inclusion, freedom, human rights and so on – the liberty, fraternity and equality of the French Revolution, which was in turn, born out of the French Enlightenment. This was full-on programmatic secularism on display. It was a classically libertarian view of freedom, the absolute freedom to choose what we do with our lives, of individual self-expression, with no overarching, universal idea of the Good, which of course is one particular understanding of what freedom means. It is distinct, for example, from an older view of freedom as gradual liberation from (and therefore the disciplining of) some of our conflicted inner impulses that are deemed destructive of the soul or of society. Secular liberalism that parades itself as self-evident, the opinion of all right-thinking people, is so often incapable of seeing how for others - Muslims and Christians for example - it is anything but self-evident. There are many across the globe who are not content with an overarching moral scheme which insists on telling them that their belief is a private matter rather than a distinct transcendent truth.

So, what if the opening ceremony was a paean to French values, rooted in the French Enlightenment? And what does that have to do with paganism?

The first volume of Peter Gay’s monumental two-volume work on the Enlightenment was subtitled: “The Rise of Modern Paganism.” He pointed out how the philosophes of that same Enlightenment - Diderot, Montesquieu, Voltaire, for example - loved Cicero, Lucretius and the rest. Every educated person at the time studied Greek and Latin, yet these men went deeper to revive pagan ideas, culture and sensuality. They wanted an undogmatic religion, with lots of options, just like paganism – and definitely not the dogma of Christianity. Behind its apparent rationalism or tolerance, the Enlightenment was, for Peter Gay, “a political demand for the right to question everything, rather than the assertion that all could be known or mastered by rationality." It was a rejection of a single creed, in favour of multiple ways of life and belief. The era harked back to the classical past, seeing itself as a completion of the Renaissance, finally leaving behind the vestiges of religion that the Renaissance still retained. The Enlightenment was, Gay argued, not so much the birth of a new rational age, but effectively a renewal of an ancient pagan sensual pluralism.

****

The argument that paganism is returning has a weak and a strong form. The weaker form is that we have returned to a kind of pluralism where there are many objects of worship under an overarching scheme that denies any of them ultimate truth or value.

Paganism was essentially pluralistic. Pagans believed there were many gods who inhabited the universe and who demanded allegiance. Pagan worship was a kind of bargain, whereby if you paid your dues to the gods by offering sacrifices to them, especially the local ones of your city, they would look after you and ensure that things went well. Yet the language of ‘gods’ is confusing. What pagans meant by ‘gods’ was not what Jews or Christians meant (or mean) by ‘God’. Pagan gods belong to nature. They do not transcend it. Pagan gods were objects within the world, rather than the transcendent source of all things, existing precisely beyond physical reality. As St Augustine pointed out, paganism took the good gifts of God and turned them into gods – objects of devotion that they were never meant to be.

If paganism was pluralistic, with numerous objects of worship, none of whom could claim absolute allegiance and who ruled over the lives of their devotees, then modern pluralism bears some distinct similarities. A pluralist public space where each of us is entitled to hold our own sense of what is sacred to us, what is of ultimate value, and where no one perspective is favoured as the one, large distinct truth, gets pretty close to a modern kind of paganism.

Of course there aren’t too many temples to Bacchus, Aphrodite, Tyche or Plutus on street corners in Paris, New York or London. Yet these were the gods of wine, love, chance and wealth. It is hard to deny that the draw of addictive substances, the lure of sex, the hope of a lottery win, or the desire to be rich do not dominate lives in our world.

There is an old saying that you can tell what someone worships by asking what they would sacrifice most for – or, to put it differently, what they think will make them happy. Worship and sacrifice always went together, whether in the Jerusalem Temple in the Old Testament, in classical paganism, or even in Christianity where St Paul urged the followers of Christ to ‘offer your bodies as a living sacrifice.’ Equally, you can tell what a culture worships by the buildings it puts up. If the classical period put up temples to the gods, the Middle Ages put up cathedrals for the worship of the Christian God, our city skylines testify that we put up countless temples to Mammon.

****

Canary Wharf skyscrapers, London.

****

The stronger form of paganism, identified by Naomi Wolf suggests that darker, older forces are coming back to haunt us. There is an argument that paganism never really went away. It continued to lurk in the corners of European societies as books such as Anton Wessels’ ‘Europe: Was it ever really Christian?’ showed.

Leslie Newbigin, perhaps the greatest Christian missiologist of recent times, spent most of his life as a missionary in India before returning to the Enlightenment-shaped west in the 1980s. As he did so, he looked back on the idea of a secular society in which there were no commonly acknowledged norms., “We now know”, he argued, “that the only possible product of that ideal is a Pagan society. Human nature abhors a vacuum. The shrine does not remain empty. If the one true image, Jesus Christ, is not there, an idol will take its place.”

In the UK, we seem about to head down the road towards ‘assisted dying’. The story of Canada should give us pause. Ever since it legalised euthanasia in 2016, stories continue to emerge of people asking for death over such problems as hearing loss or a lack of housing, or feeling they are a burden on their families or the state, and where not just old people are candidates for death – there are now calls for unwanted babies to be killed – we are back with infanticide. In Quebec and in the Netherlands, one in 20 deaths now are self-chosen. In Belgium, such deaths have doubled in the last 10 years.

If Louise Perry and Naomi Wolf were among those to spot a re-paganisation of culture, it is no accident that both were women. Paganism was bad for women. Tom Holland’s book Dominion was born out of the insight that our world is very different from the classical pagan one. A world where entertainment meant watching wild animals tear the flesh off slaves, where unwanted babies were routinely abandoned, where masters could have sex with whoever they wanted, and could effectively rape young female slaves was a very different world from ours, where such behaviour is criminalised. And for him, the difference was Christianity.

The problem was, as the early Christians pointed out, that the gods enslave. If you give yourself over entirely to drugs, sex, money or Dionysian pleasure, ultimately, they will rule your life, enslave, and destroy you, as many an addict has discovered. We were never meant to give ourselves to such temporal things – only God, they said – the transcendent source of all goodness - can satisfy and liberate from destructive desire.

Maybe Eliot was right. It takes a long time to put down religious roots. Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism are only recent imports to Europe and so have shallow roots here. Both Christianity and paganism have gone deep into our soil. Secular pluralism, especially the ‘programmatic kind, always veers backwards towards another version of paganism. And so, European culture only really has two options – the paganism that lasted for centuries before the arrival of Christianity, and the Christianity that replaced it.

The Olympics offered us two paths. The one offered by the creators of the opening ceremony, the other by the athletes who see a higher goal than a gold medal or earthly fame. The creators of the opening ceremony may not have intended an attack on Christianity. Yet they were happily acclaiming something which Europeans left behind long ago. And we should pause before we celebrate that.