The first commercial Christmas card was sent in 1843, 180 years ago, but is this relatively recent tradition of sending Christmas greetings by post slowing dying a death? The result of the combined impact of environmental concerns, online options and the increased cost of postage? What images have characterised Christmas cards over that period and how will you choose the perfect Christmas image to send, whether digitally or in the mail?

The UK’s Royal Mail estimates that it still delivers 150 million cards during the Christmas period while other sources claim that one billion Christmas cards are sold in the UK annually. As a result, the traditional Christmas card is still going strong.

The tradition was established when Sir Henry Cole, the founding director of the V&A, sent the first commercial Christmas card as a way of responding to the flood of Christmas and New Year letters that he and others had begun to receive following the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post. Cole, who had been involved in the introduction of the Penny Post, commissioned the artist John Callcott Horsley to design a card and advertised it in the Athenaeum paper as “A Christmas Congratulation Card: or picture emblematical of Old English Festivity to Perpetuate kind recollections between Dear Friends”. Horsley’s design is a triptych with a central family party scene, in which three generations drink wine to celebrate the season, offset by two acts of charity – “feeding the hungry” and “clothing the naked” – which derive from Jesus’ Parable of the Sheep and the Goats.

In this period card companies would commission designs from significant artists or hold competitions to produce new designs, while Christmas card designs themselves were reviewed in the national press.

Early Christmas cards featured flowers and religious symbols including angels watching over sleeping children. However, George Buday, in his book ‘The History of the Christmas Card’ (1954), suggests that, “the Christmas card from its beginning was more closely associated in the minds of the senders with the social aspect – the festivities connected with Christmas than with the religious function of the season”.

By the 1880s, a prominent card-maker, Prang and Mayer, was producing over five million cards a year and this expansion saw the now familiar iconography of Christmas established: “winter scenes of robins, holly, evergreens, country churches and snowy landscapes; along with indoor scenes of seasonal rituals and gift giving, from decorating trees and Christmas dinner, to Santa Claus, children’s games, pantomime characters and Christmas crackers”. In this period card companies would commission designs from significant artists or hold competitions to produce new designs, while Christmas card designs themselves were reviewed in the national press.

Card companies, of course, also recognised the value of utilising great art from the Western tradition, particularly the art of the Renaissance. As art critic Jonathan Jones has noted:

“Great art comes tumbling through your letterbox at this time of year. Here are the kings from the east laden with gifts, gathering at a stable where an ox and an ass look lovingly at a baby child. Mary sits demurely. Shepherds hearken to an angel. You pop it on the mantelpiece with all the other cards.”

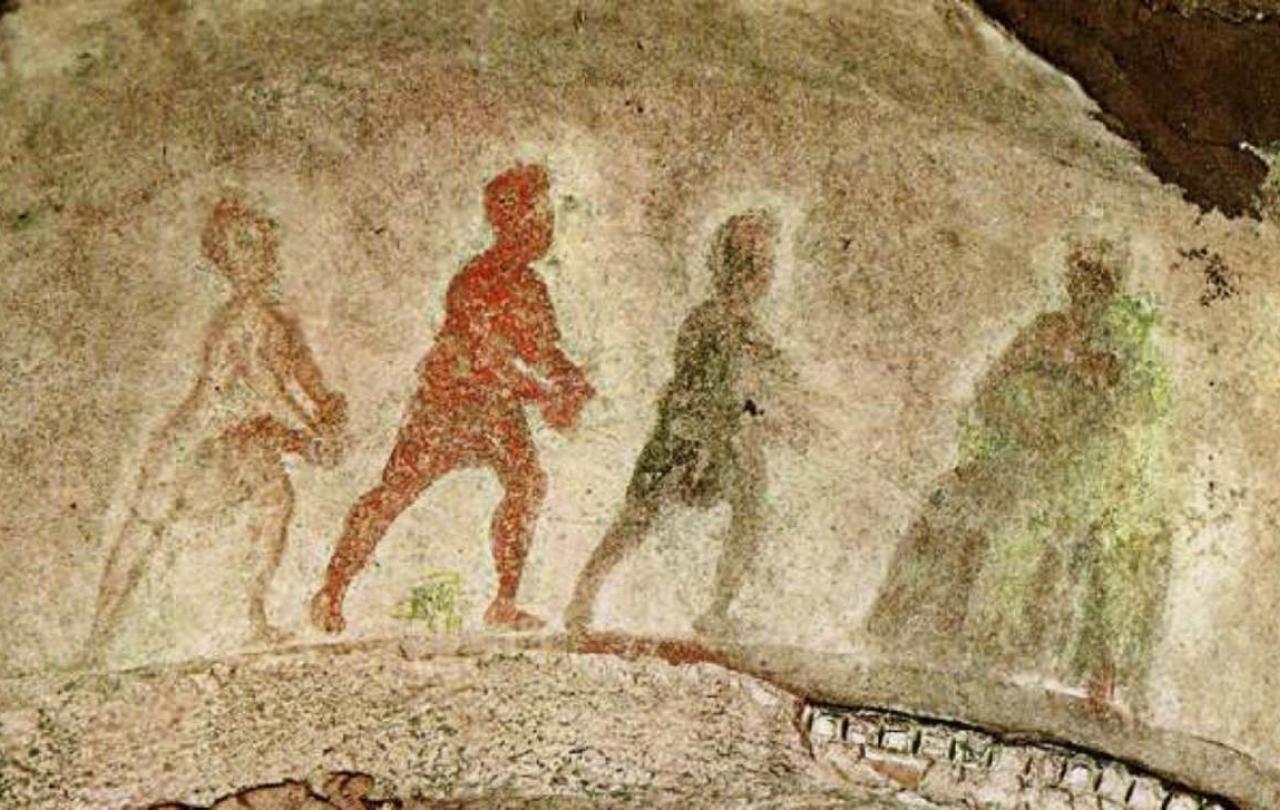

Although the earliest nativity we know of dates back to the third century - being a stucco preserved in the catacombs of Priscilla, in Rome - when we think “Nativity,” we are probably, as Victoria Emily Jones has noted, thinking of church art from the Renaissance “because the Church held particular sway at that time, in that place”. The National Gallery’s exhibition 'Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed', by highlighting an overlooked Renaissance artist, demonstrates the extent to Renaissance art centred on the life of Christ, with a prominent place for nativity scenes. Their choice of December for the opening of this exhibition shows the extent to which we associate such art with the Christmas season. The exhibition includes beautiful renditions of a ‘Virgin and Child’, ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’ and ‘King Melchior Sailing to the Holy Land’.

“Historical accuracy is not the point; the point is to see Jesus as the Savior of your own people, as incarnated very close to you, and relevant to life today”.

Victoria Emily Jones

Victoria Emily Jones also notes that, to illustrate the truth that “Jesus Christ was born for all people of all times”, Christians around the world, including during the Renaissance, often depicted him “as coming into their own culture, in the present time”. This realisation also provides one way to search for images of the nativity more relevant to our own cultures and time. Jones has made this a particular feature of her independent research on Christianity and the arts.

Noting that “the center of Christianity has shifted”, being “no longer in the West”, she suggests that, if we survey the Christian art being produced today, we will see that “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, and the settings they inhabit, have a much different look”. Mary may be “dressed in a sari or a hanbok”, Jesus “wrapped in buffalo skin, or silk” and, instead of oxen and asses, we may “see lizards and kangaroos”. As she writes, “Historical accuracy is not the point; the point is to see Jesus as the Savior of your own people, as incarnated very close to you, and relevant to life today”. Accordingly, she has provided online two series of contextualised images of the Nativity painted within the last century with each work bringing “Jesus into a different place, in order to emphasize the universality of his birth”.

Additionally, she also made use of a meditation I had written, which has as its refrain the plea “Come, Lord Jesus, come”, to create an Advent series of images and reflections exploring “what it meant for Jesus to be born of woman—coming as seed and fetus and birthed son”. Again, in her selection of images, she took “special care to select images by artists from around the world, not just the West, and ones that go beyond the familiar fare”. As a result, in ‘Come, Lord Jesus, Come’, there are images of “the Holy Spirit depositing the divine seed into Mary’s womb; Mary with a baby bump, and then with midwives; an outback birth with kangaroos, emus, and lizards in attendance; Jesus as a Filipino slum dweller; and Quaker history married to Isaiah’s vision of the Peaceable Kingdom”.

Her hope is that “these images fill you with wonder and holy desire—to know Christ more and to live into the kingdom he inaugurated two thousand-plus years ago from a Bethlehem manger”. She quotes S. D. Gordon’s “succinct summary of the Incarnation” - Jesus coming into this world as both God and human being - “Jesus was God spelling Himself out in language humanity could understand” in order to suggest that these images “celebrate the transcendent God made immanent, accessible” and “celebrate his new name: Emmanuel, God-with-us”.

Whether you are looking to continue the tradition of sending Christmas cards through the post or will be sending digital greetings to family and friends, looking for, creating or commissioning nativity images that depict Jesus coming in your culture and your time continues to offer a significant way of showing the wonder of the incarnation to others. And, if you do so, while being entirely contemporary, you will also be firmly rooted in art history and church tradition.

Explore more nativity art

Victoria Emily Jones has curated two collections of nativity art.: 2011 collection, and 2015 collection.

She has also compiled an Advent Slideshow and Devotional for Art & Theology.

Visit BAME Anglicans' Paintings of the Nativity From Around the World.

View a selection of nativity scenes curated by BAME Anglicans.