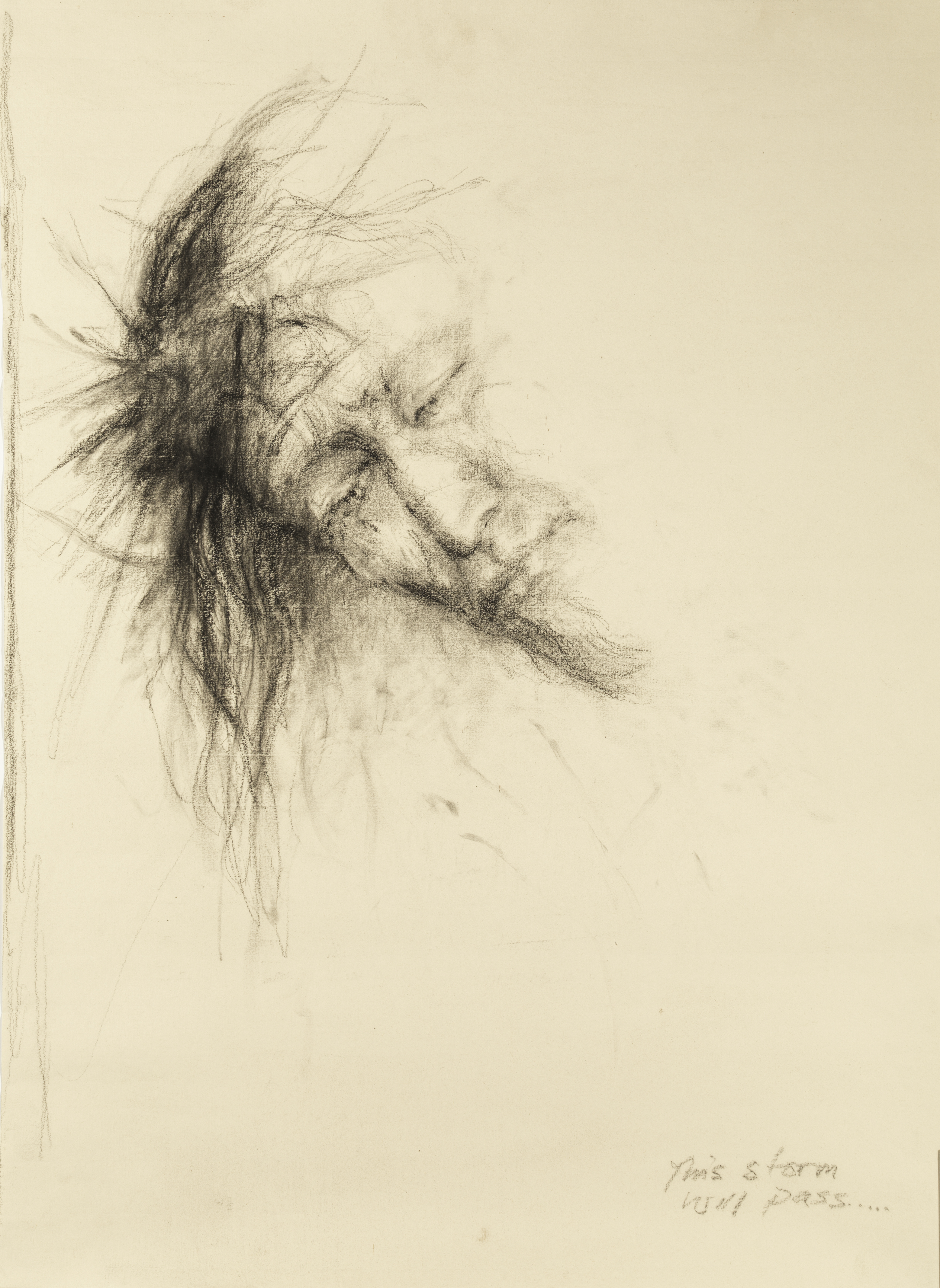

It takes a moment to grow accustomed to walking in the dark of the long, steeply roofed room that houses Mat Collishaw’s art installation Eidolon. But the artwork’s impact is immediate. Two huge, moving images in the middle of the room show a blue iris flower. It is being engulfed by flames but not consumed. Speakers play, in Latin, a story from the Hebrew bible’s Book of Daniel in which three young Jewish men survive being thrown into a fiery furnace for refusing to worship the Babylonian king. The artwork is a rare successful attempt to capture in modern art the essence of Christ’s crucifixion and the Christian tradition of martyrdom, with its roots in earlier Jewish beliefs.

Watch Eidolon

Eidolon is one of the highlights of the UK’s first Faith Museum, a bold project opened on October 7 in Bishop Auckland castle, the historic residence of the Bishops of Durham. The museum forms part of The Auckland Project, a series of initiatives in Bishop Auckland, north-west of Darlington, being funded by Jonathan Ruffer, a Christian and successful City investor. Ruffer’s childhood home was outside nearby Middlesbrough. The new institution aims to tell the story of 6,000 years of faith in Great Britain, starting with the Gainford cup and ring stone. The stone, found 90 years ago 10 miles from Bishop Auckland, may date from as early as 4,000BCE. It features carvings regarded as the earliest evidence of religious practice in Great Britain.

Jonathan Ruffer.

Ruffer, however, declines to link the museum’s contents to his own faith or an explicitly Christian message. He insists that he is merely seeking to advance discussion of faith in a society where it is little debated but remains a potent force. In the living room of Castle Lodge, his home in the castle grounds, Ruffer compares the contemporary taboo about religion with the very different mores of the 19th century.

“Nobody talked about sex in Victorian times,” he says. “It’s impossible to imagine that because the public world was silent on it, it was not as much a guiding force as it is today. I think that’s where faith is now.”

He adds that the 10-year process of establishing the museum has made it “absolutely apparent” to him why there are no other similar institutions.

“What is a museum for?” he asks. “It’s to gawp at things and if you think what is the subject matter of a faith museum, it’s God. In whatever form and shape that you believe that God to be, you cannot see that topic.”

The museum is nevertheless rich in sometimes poignant objects that the curators call “witnesses” of faith. They include the Binchester Ring, a ring with Christian symbols dating from the third century of the Christian era. The ring, found only a mile from the museum, is regarded as the earliest known evidence for Christian practice in Britain. There is a small slate, engraved on one side, that served as an altar for Recusant Roman Catholics while their Church was out in the cold and had to stay hidden during the Reformation years. The slate could be turned over and disguised as a normal roof slate when not in use. The museum has on loan the Bodleian Bowl – a rare example of a ceremonial vessel used by one of England’s Jewish communities before King Edward I expelled the group in 1290.

Ruffer says the impact of the objects – many on loan from other museums - comes from their histories.

“There’s a great power in the objects that we have,” he says.

Eileen Harrop.

Among the advisers on the museum’s establishment was Eileen Harrop, a Church of England priest originally from Singapore and of Chinese origin. She was appointed an “entrepreneur priest” in 2016 to work with Ruffer on The Auckland Project. Meeting in the castle’s former library, she says the museum avoids suggesting all faiths are the same, while also steering clear of Christian proselytising. Harrop, now the vicar of four parishes around Bishop Auckland, expects the museum to have a powerful effect on visitors.

“It allows for people to experience the God who led Jonathan here,” she says. “It allows for people to enter into all the different ways in which people can identify something about faith and then it’s up to God.”

A visit’s emotional impact comes largely from the new institution’s first floor, devoted to works created by contemporary artists exploring faith. Some of the most powerful exhibits are black-and-white pictures in which Khadija Saye, a young British-Gambian artist, explores possible uses for religious objects belonging to members of her family, some Muslim and some Christian. Saye lost her life in the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire.

A series of works by Christian painter Roger Wagner has proved particularly timely. The museum opened the same day that Hamas terrorists started the current Israel-Gaza war with their attack inside Israel. The paintings translate stories from the Christian New Testament to the contemporary, riot-scarred occupied West Bank.

Eidolon is among the works on the first floor. Harrop calls it an “amazing installation”, particularly for its retelling of the story of Daniel.

“It relates a story… of what was going on in that particular experience of the faithful person called and protected with his companions in relation with God and the power of faith,” she says.

Ruffer, meanwhile, shies away from expressing spiritual aspirations.

Asked how he hopes people will respond to the museum, he says: “I couldn’t care less – that’s up to them. I have many faults but a sense of wanting to tell people or persuade people how they should be is very low down the list.”

Yet Ruffer is clear that he received a clear, divine call to come to Bishop Auckland. He was first drawn to the area by his enthusiasm for Spanish art and his determination to prevent the Church of England’s Church Commissioners, then owners of the castle, from selling its prize artworks – life-size, 17th century portraits by Francisco de Zurbarán known as Jacob and his 12 Sons. The paintings, saved for Bishop Auckland in 2011 by a multi-million-pound donation by Ruffer, remain in the castle. But the Zurbarán link inspired Ruffer to establish a Spanish Gallery, dedicated to art from Spain, on Bishop Auckland’s Market Place.

“I came here really through a calling,” Ruffer says. “I felt the need really to drop everything and come up to somewhere in the north-east, to be part of a community.”

Ruffer’s engagement with the town deepened when the Church Commissioners announced, also in 2011, that they planned to sell the castle. Auckland Castle was formerly a seat of both ecclesiastical and secular power when the Bishops of Durham were prince-bishops – uniquely in England, both secular governors and bishops. The bishops lost the last of their secular powers in 1836. Ruffer bought the castle and transferred ownership to a newly established Auckland Castle Trust, which became The Auckland Project.

“I’ve heard from people who have through it who have said they can’t really put their finger on what it is, but they must go back again,”

Ruffer accepts there are issues with trying to capture the imagination of Bishop Auckland’s 25,000 inhabitants from inside a castle whose imposing entranceway symbolises its symbolic role as a seat of sometimes oppressive power.

“That sense of power is felt as a reality by people,” he says. “But it’s empty. Power has long since moved away from the prince-bishops and then the bishops.”

The castle’s unique history nevertheless makes it the ideal setting for the museum, according to Ruffer. Exhibits are housed both in a wing of the historic castle and a new, purpose-built extension. Ruffer says the castle was a far better place to site a faith museum aimed at raising questions than somewhere more explicitly linked to a specific faith such as a cathedral close.

“Auckland Castle has been intricately involved with faith for nearly 1,000 years and yet it hasn’t been a place of worship,” he says. “It has a chapel but it’s ecclesiastical without being a cathedral, church or minster. So it seemed to me that that made it very appropriate for a faith museum.”

The early signs, according to both Ruffer and Harrop, are that the new institution is encouraging reflection among visitors. Ruffer says the museum has responded to the “elemental need” for faith. He adds that the positive reaction so far vindicates the initiative to establish the museum, which he says has brought together objects and described them “without any directional guidance as to which works”.

Harrop reports that visitors seem to feel the need to experience the museum a second time after a first visit.

“I’ve heard from people who have through it who have said they can’t really put their finger on what it is, but they must go back again,” she says.

Ruffer identifies the museum’s power by saying that it gives people an easier experience of the divine than would otherwise be available to them. He compares the experience of encountering God through the museum to looking at the light of the sun as reflected in soft moonlight. That, he points out, is far easier than looking painfully and directly at the sun.

“The thing that changes people is to be confronted with something bigger than yourself,” he says.