This year’s UN climate talks have come to an end with a headline-grabbing figure, reports of deep divisions and cries of failure. How do we understand the legacy of these negotiations for us now and for the generations to come?

COPs bring together negotiators from almost 200 nations, along with tens of thousands of people from across business, civil society and local communities. They gather to make decisions about this crisis that touches every community and part of our lives and our world, though not equally (which is part of the issue). The annual negotiations are the culmination of months of action and diplomacy. The negotiators pore over draft texts to understand the implications of a new set of brackets, they search for sources of free coffee to power them through the increasingly sleepless fortnight, and scrabble at the end to land on a consensus.

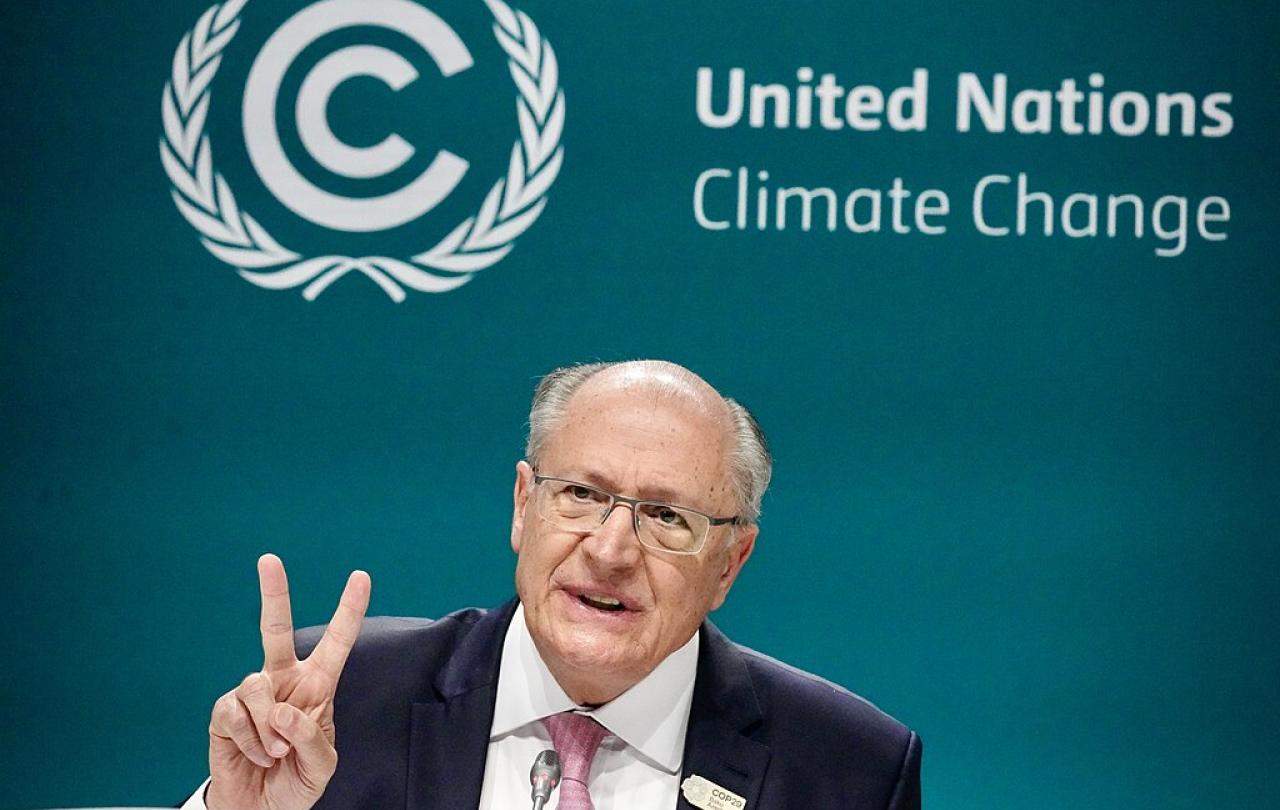

At COP29 this year, the key things at stake were a new finance deal that was three years in the making and a wave of 2035 national climate targets. Lurking amongst discussions were the implications of the US election results. The pressure was on to land strong decisions before Donald Trump – who withdrew the USA from the landmark Paris Agreement on climate last time he was in office and has stated his intention to do so again – returns to the White House.

What did we get at the end of all of this?

Finance in the spotlight

The new finance goal of at least $300 billion per year by 2035 for lower-income countries seems like a big number, but is around a quarter of what is needed, $1.3 trillion. For what was dubbed 'the finance COP', wealthier nations came with a distinct lack of actual money, despite their obligations towards those countries least responsible and hardest hit by climate change. The $300 billion could be spun as a tripling of the previous commitment of $100 billion a year – but taking into account inflation, it’s nowhere near that in real terms. And it’s not just about the quantity; much of that money is likely to be loans, driving already strapped countries even further into debt.

When lower-income countries argued for that $1.3 trillion, this wasn’t them trading Pokemon cards in the playground. It was about the very existence of people and whole communities. Climate Action Network, a global network of over 1,900 civil society organisations, labelled the outcome a betrayal, while India's delegate Chandni Raina called the final text “little more than an optical illusion”.

To build meaningfully from this, the last-minute addition about using the next 12 months to develop a roadmap towards that $1.3 trillion needs to be a priority. This finance could come from sources such as taxes on shipping, aviation and the wealthiest in society. This money would be an investment in the world we need – more secure and stable in the face of growing climate chaos and more frequent flooding and storms.

Emissions reductions left in the dark

The other key test of this COP was meant to be the countries’ national climate commitments which are due to be updated and strengthened by February next year at the latest. Despite this, the UK was one of just a few countries to come with a new target. In Baku, nations had the opportunity to collectively agree how they will implement the commitments from last year to transition away from fossil fuels – but kicked those decisions to next year. This is in the context of plateauing action to curb warming; since 2021 we have been on a path toward 2.7°C by the end of this century. (This analysis suggests the recent election of Donald Trump could add 0.04 °C of warming due to rolling back US climate policies; not good, but not the derailing some feared. The potential impact on collective action is as yet unquantified.)

A mirror to the world

Questions are inevitably being asked about these COP events: are they “no longer fit for purpose”? Is it time for something else to deliver the scale and urgency of action required?

I was struck by the words of Alden Meyer, with his 40 plus years of experience in climate policy:

“COPs are where the world holds a mirror up to itself to see how well it is doing in the fight against climate change; when the image in the mirror is ugly, it does little good to blame the mirror.”

We do not like what we are seeing. Two weeks of tough negotiations culminating in imperfect outcomes expose our frustration with the rate of our change. They magnify our longing for COP to solve this crisis that frightens and overwhelms us.

But COPs are only as good as the governments, businesses and people that will turn the agreements into lived reality. That’s why those national climate plans due next year matter so much. This mirror indicates that climate seems to have slipped a little down the priority list, despite the growing urgency.

The mirror analogy is a good one – but we also need to recognise where there are vested interests who would obfuscate what we see and what is decided. Among the thousands who descended on Baku were 1,773 fossil fuel lobbyists — more than all delegates from the ten most climate-vulnerable countries. This is part of a recent trend of outsized influence by those who would invest against our collective future for the profit of burning more fossil fuels.

Weeks like last one remind us of the flaws in the COP process – but the answer is not to ditch the whole thing. COPs are the only forum where every country is heard on this global issue. Existing power imbalances are reflected and needed to be addressed; a concrete finance figure only appeared on the last scheduled day of negotiations, putting lower-income nations were under pressure to accept it as clock ran down. In the final hours, several delegations walked out of a meeting to express their frustration with what was on offer.

COPs provide a space for civil society, youth activists, faith and community leaders to speak into global decisions and shape the world and our future. Getting the agreement we got is in part testament to the advocates who kept finance solutions on the agenda.

The COP processes need to be made fairer and more accountable, to steer a clearer way forward for climate action of the scale and speed we need. But if we scrapped them, we’d only need to create a different space for international diplomacy in their place – and we certainly don’t have time for that.

We see only in part

Ultimately, our disappointment with COP shines a light on our longing for a more hopeful future. It would be easy to let weeks like the last one harden or discourage us. But legacies are hard to see in the moment. Prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement, we were headed for at least 3.5℃ of warming by the end of this century; a catastrophic change to our world and inheritance for future generations. COPs have played a key role in shaving almost a degree from that trajectory. It still isn’t enough, but it isn’t nothing.

COPs show us something of the world as it is – messy, broken and yet suffused with people devoting themselves to justice again and again. For many, there’ll be some much needed rest to catch up on, because this is a race for the long haul. We live and act and speak for justice knowing that legacies don't fit nearly into a headline or media quote. They are slower to be realised and understood. The challenge to us all is to keep sowing faithfully, knowing we may not be the ones to reap in our lifetime. To keep acting in love and hope – even when the end is not in sight.

One of the early church leaders, Paul, wrote in a reflection on love: “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face.”