The most significant political revolution of the modern era was not that of America, France, Haiti, Russia, or China. It was the longer lasting, deeper rooted, and more pervasive revolution that is “humanitarianism.” Rather than a change in one form of political order, it was a revolution of moral sentiment that affects all political orders. The fruit of this revolution is that the acme of moral action is no longer love for a proximate “brother” but love for a remote “other.”

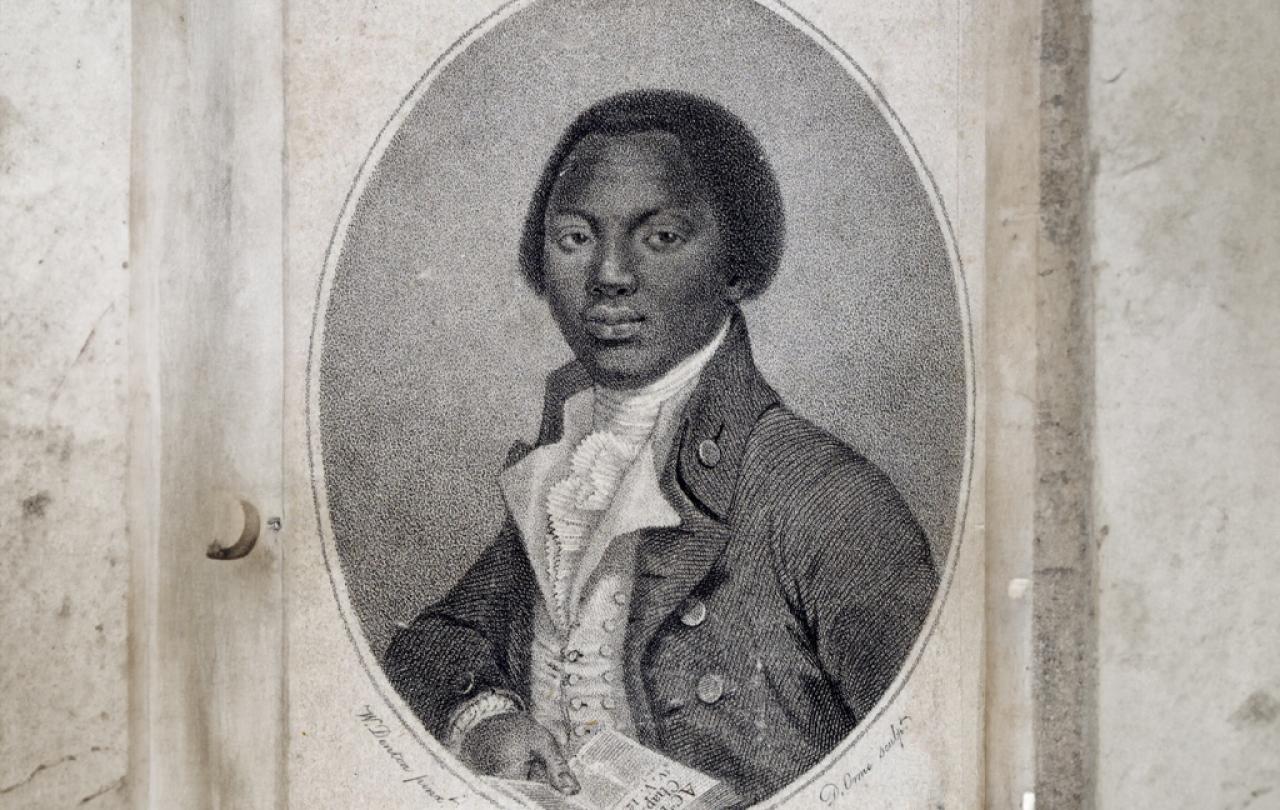

A foundational text in this revolution is Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (1789). Equiano, a formerly enslaved person, was a key activist in the movement to abolish slavery. Published on the eve of the Parliamentary enquiry into the slave trade and three months before the French Revolution, his autobiography was hugely popular, running to nine editions and numerous printings during his lifetime.

His autobiography is vital reading because the abolition movement in which he played such a key part is widely understood by historians as foundational to the birth of humanitarianism. It is also seen as providing the template for other, subsequent movements for social justice.

Equiano’s work and its impact needs situating within what is called the Second Great Awakening, a moment of religious fervour on both sides of the Atlantic. Dated as beginning in 1790, the Second Great Awakening represented a huge revival in popular Christianity. Out of it came modern evangelicalism. However, unlike its contemporary expression, the evangelicalism of the late 18th and early 19th century was a key influence on a number of movements for social reform, including the abolition movement.

In his narrative, he portrays himself as the true Christian and the true human. When he encounters the European slave traders on their slave ships, they are the real savages, and despite what they say, they are not Christians.

At the heart of Equiano’s Narrative are two stories of conversion. The first is his conversion to Christianity. The second is his conversion to abolitionism. These two conversions are interrelated. Through his conversion to Christianity, he discovers an understanding of what it means to be human that leads him to see all forms of slavery as wrong. This judgment against slavery includes not just the industrial scale form of slavery driven by the plantation economy, but also what some see as the more benign forms of his own Eboe society in West Africa.

Through his conversion narrative he gains possession of himself, his history, and his people as historical subjects able to speak and act for themselves. He becomes a political actor contributing to and a leading figure within a new political form – the social movement – that contested a dominant feature of the political economy – slavery. Crucially, he refuses and refutes the racialized ways in which Africans are negatively portrayed. Rather than a chattel, he is a Christian and a citizen with a story to tell. He is not merely biology to be exploited. He has a biography. And he is one whose testimony stands as evidence in the case against slavery. In staging this claim he reverses the order of who listens and who speaks – he speaks and English readers listen and take instruction from him.

In his narrative, he portrays himself as the true Christian and the true human. When he encounters the European slave traders on their slave ships, they are the real savages, and despite what they say, they are not Christians. He also represents himself in the text as a new St Paul. He’s an apostle calling others to discover both Christ and their humanity in their encounter with him through reading his story.

Equiano’s is a profound and original work that constantly draws on Biblical frames of reference to both denounce the world as it is and announce a new world. The Bible for him is simultaneously a means of demanding recognition and offering critique.

In the frontispiece of the book he is pictured as holding a Bible which is open at the Book of Acts in the New Testament. Acts chronicles the adventures of the apostles after Christ's death and resurrection. The frontispiece is the key to understanding the story Equiano tells. He is not Odysseus who returns home after many trials and tribulations. Rather, he is St Paul: one who becomes an apostle, taking on a new name and identity in the process. Like St Paul, Equiano suffers whipping, imprisonment (in the hold of a ship), storms, and travels in chains all for the sake of preaching the Gospel. And like St Paul, who ends his journey in Acts in Rome, Equiano’s journey leads him finally to London, the centre of his imperial world. From there he writes an epistle addressed to the churches who are failing to be faithful to the Gospel. In doing so, he appeals, like St Paul, to a universal humanity now available in Christ, in whom “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

The most significant political revolution of the modern era was not that of America, France, Haiti, Russia, or China. It was the longer lasting, deeper rooted, and more pervasive revolution that is “humanitarianism.”

There are those who read Equiano as simply a stooge for colonialism and capitalism. Yet they fail to convince. Such readings deny any connection to the abolition movement. And rather than being someone who is reclaiming his voice and agency, they turn him into a faceless and voiceless subject of forces beyond his control.

To dismiss Equiano is to fail to see the truly revolutionary nature of the text he wrote. In his autobiography, Equiano describes the Christian masters who brutally tortured their slaves for the slightest offense, the ubiquitous rape of women, including very young girls, and the theft from slaves who had little or nothing. Alongside and in stark contrast to this brutality, exploitation, and alienation, Equiano narrates an alternative world, one characterized by intimacy and connection. In this world, he becomes friends with women and children, and forms equal partnerships with white men. The vision of freedom he presents does not entail violently taking control of the state (as was the pattern set by the French revolution). That vision of revolution simply changes who is in control of the state and the economy but does not change the basic form and character of relations between people.

The freedom Equiano portrays is neither structural nor economic. Rather, he bears witness to a revolution of intimacy and sentiment. His life story embodies a changed structure of feeling, one where in place of the rape, whipping, chains, fear, disgust, and disdain that rules relations between blacks and whites there is the possibility of mutuality and respect. Equiano’s autobiography continues to reverberate as it calls us to a conversion of our hearts and mind so that we encounter others––no matter who they are or where they come from––as neither objects to exploit nor enemies to be feared but as neighbours in need of care. Such neighbour love may well be a fragile basis for hope in a world of carnage and desolation still living in the after lives of slavery. Nevertheless, it is as revolutionary now as it was in Equiano’s day.