We’ve all seen them – haunting images of starving children, flies on their faces, begging for help – powerless to change the cruel lot they’ve landed in life… There’s more to the story, though. More to the people in the pictures.

Extreme poverty is a very real problem. The living conditions faced by many around the world are, indeed, truly devastating, and in hoping to urge a response and to help, we can fall into a clichéd portrayal (and understanding) of need that strips people of a sense of dignity and agency.

But, the answer to poverty can be uplifting, sustainable, restorative and empowering: the answer can be the Church.

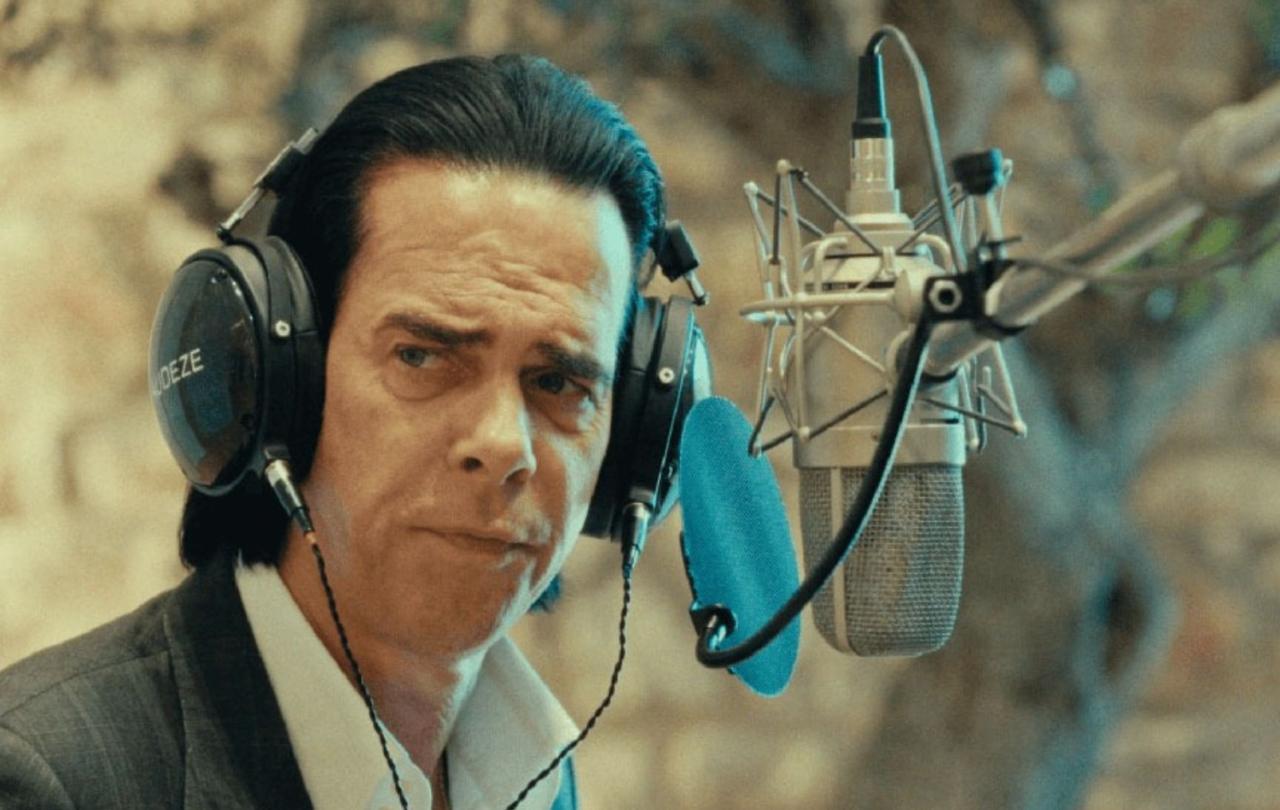

You may have seen Tearfund’s new TV ad. If not, you can watch it now. With some humour it challenges some of the stereotypes about how those in the developed world go about trying to eradicate poverty elsewhere.

The ad shows a number of excellent things that a community in Burundi has achieved which have transformed the lives of the people living there. It features them talking about the training that made it possible – but what is this training? And what does it have to do with Tearfund or the church?

Well, here’s how it works:

It all starts with Bible studies. These are designed to help people identify the skills and resources that already exist within their community, and to see new ways they can use them to respond to their needs.

Local church members (or leaders) receive training to facilitate these Bible studies and share the message within their community.

Each Bible study ends with a call to action. This may be something small to start with – like a change in a harmful way of thinking – but can quickly grow in scale to things like improving or building schools, health centres and roads.

Tearfund and our local partner organisations help to provide the practical knowledge and skills training needed to make it possible to carry out these plans.

In this way, churches and communities can find themselves working together to lift themselves out of poverty for good and to realise their God-given potential and thrive.

I played my part in the construction, even if I was not strong, I worked with others in digging the road and moving rocks.

The ad features Cecile, a young married mum with one daughter. She tells us her experience:

‘We understood the power of coming together as a church and working together for our own development. A changed church changes the community for the better. Our congregation was able to build a health centre, a road and bring up water.

‘I am happy to be part of this church as I come to know God and see his hand. I now have a church family, we love and support one another. I played my part in the construction, even if I was not strong, I worked with others in digging the road and moving rocks, and we also contributed some money.

‘It is like an awakening. People are more engaged, we have been inspired to change and to change our community and we are now active.

‘Apart from building the health centre, more people are working hard to change their situation. Some have started small businesses, I’ve also been selling vegetables and I hope that once I get enough capital, I’ll be able to start a small business at the market and earn more money to help [me and my husband] improve our lives and build a house.’

Every day, thousands of people around the world suffer and die because of poverty. Christians don’t believe that this is God’s plan. At Tearfund we believe that the church is part of his plan to respond – and that we all have a part to play in ending extreme poverty.

Is the church even still relevant though?

Here in the UK, it might seem strange to be so focused on faith and the church. The most recent census showed that, as a nation, we have a steadily declining affiliation with Christianity, and the news last year made much of the fact that only around ten per cent of the population regularly attend a church service. It might be worth wondering whether the church has lost some of its ability to influence change.

Almost three million UK adults sought help from churches or faith organisations because of the cost-of-living crisis.

In England, Anglican bishops are still members of the House of Lords, so they have some voice, but for the rest of us…why the faith? Where does God fit into things and is the church even practical or relevant in society these days?

It actually works

In spite of the declining number of worshippers, in 2022 almost 3 million UK adults sought help from churches or faith organisations because of the cost-of-living crisis.

During the worst of Covid, churches across the country provided a hub for making sure the most vulnerable in their communities were fed and provided for. Many church buildings became food preparation and distribution centres and local church members became temporary delivery drivers.

The local church around the world

In the same way, around the world, the church is often first on scene in times of need.

From its unique position right within a community, the local church knows intimately the needs of the people it serves.

And in many places where Tearfund works, the church has a significant and trusted influence, giving it a voice for change and for justice in society.

The church, as a vehicle for transformation, has the capability to work powerfully and effectively in a way that lasts.

No matter where it is, the Christ-following church has always been about the transformation of lives and about community: called by Jesus to first love God (allowing him to transform Christians’ own lives), and then to love our neighbours as ourselves (bringing transformation to our communities).

More than could, the church should be the answer to poverty.

The church is a sustainable, efficient, empowering and highly cost-effective way of helping whole communities lift themselves out of poverty.

The church (in all its various forms and denominations) is the largest non-governmental, non-profit organisation on the planet. Tearfund itself was born out of the church, and recently an independent study that we commissioned confirmed in numbers what our own experience, stretching back over 50 years, had already shown us: the church is a sustainable, efficient, empowering and highly cost-effective way of helping whole communities lift themselves out of poverty.

By equipping the local church within a community facing poverty to find solutions to their needs, the people being supported can become agents in their own rescue.

Like many charities, there are questions about the impact they have. Just how effective is working through the church really?

In fact, researchers discovered that a social value of £28 was released for every pound invested in community transformation work through the church.

Practically, that means that when compared to people in communities that had not received training and equipping through the church, those that do are:

- 27% more satisfied with their lives in general

- 113% more likely to work with others on shared projects

- 51% more likely to have maintained or increased their income in the last year

- 46% more likely to speak up and raise issues with decision-makers

- 62% more likely to have invested in assets, such as property or livestock in the last year

- and 26% more likely to feel confident they could cope with unexpected events in the future.

Working through the local church has the power to bring positive, whole-life transformation which spreads throughout a community – so that even those who aren’t directly involved in the activities still experience some benefits.