The last episode of Friends was aired in the UK on Channel 4 on 28th May 2004. You may have been one of the 8.6 million people who watched the hour-long farewell special.

It marked the end of an era which began when the first episode had aired on NBC on 22nd September 1994. The Berlin Wall had come down, the Cold War had thawed out and Francis Fukuyama had recently published The End of History and the Last Man. The Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre Life were still standing. Life was good. Eat, sip coffee in Central Perk and be merry. One day, sociologists may study the effect Friends had on the popularity of Starbucks.

For a whole decade, we became intimately involved in the lives of these six much-loved sitcom characters – and Gunther. No-one cared about Gunther. He was in love with Rachel. Big deal. Who wasn’t? ‘The Rachel’ became the name of an internationally known haircut. Jennifer Aniston became world famous, eclipsing movie stars who queued up to be in Friends. We’re talking about A-List movie stars who didn’t do television. This was the 90s. Movie stars were above the everyday, story-of-the-week, dreary medium of television, especially corny, studio sitcoms.

Everyone wanted in on Friends. So Central Perk was graced with the presence of Brad Pitt, Julia Roberts, Bruce Willis, Reese Witherspoon, Tom Selleck, Elle MacPherson, Gary Oldman, Robin Williams, Billy Crystal, Alec Baldwin, Susan Sarandon, Helen Hunt, Danny Devito. They were all great. But we didn’t love them. We loved Chandler, Monica, Phoebe, Joey, Ross and Rachel. They were, well, our friends.

'It’s like your favourite biscuit, burger or takeaway. You know what you’re getting. You love it. It’s the same every time.'

Reliably funny

Why? How? What was the appeal? Let’s just acknowledge one key reason: it was really funny. It’s reliably funny. I can still remember the thrill of excitement on a Friday. The whole evening was planned around watching Friends because I knew it would not disappoint. And that’s what the audience is looking for. It’s like your favourite biscuit, burger or takeaway. You know what you’re getting. You love it. It’s the same every time. An episode of a sitcom is meant to be that kind of snack. It’s familiar and comforting. I should know this. I’m a sitcom writer.

I remember Friday 28th May 2004 extremely well. On BBC1, my episode of My Family was being aired. The guest star wasn’t Sean Penn or Ben Stiller. It was a brilliant but not-yet-very-famous Peter Capaldi. Ironically, he was playing someone who was as famous as some like Colin Firth. On My Family, we had to manufacture glamour. Friends just had it. It had so much, it didn’t know what to do with it.

My episode of My Family still pulled in 4.48 million viewers. That seems like a lot now, but the safe, mainstream British family sitcom was no match for the achingly cool residents of Manhattan swapping gags over their lattes.

'But our hearts yearn for that lifestyle. It’s a metropolitan Neverland. We know it’s not real.'

Aspirational

Friends is achingly cool. That’s ‘aspirational’ in marketingese which, in plain English, means ‘unrealistic’. There is no way those characters could afford to live in those flats in Manhattan. Monica’s place is neatly explained away through some aging relative, but Chandler’s flat across the hall cannot possibly be within his reach, especially as his flatmate is an actor. But no-one cares. We know people aren’t that funny. We know that life isn’t so neat. We know that you just never get a seat on the sofa in that coffee shop. But our hearts yearn for that lifestyle. It’s a metropolitan Neverland. We know it’s not real. We get it. It’s a sitcom.

But times – and hairstyles – are different now. Plenty of sitcoms come, do well, and go, but aren’t watched two decades later (see The Brittas Empire, Brushstrokes and Goodnight, Sweetheart). Friends is still huge. It’s worth so much money that if I quoted some numbers at you about syndication deals, they would be meaninglessly large. You might as well say that the rights to 236 episode of Friends have proven to be worth at least one brand-new state-of-the-art aircraft carrier with a ten year service contract.

That’s because, despite exciting new shows like Stranger Things, Andor or The White Lotus, people are still watching Friends, including teens and twenty-somethings who feel this is ‘their’ show. Even though it was my show.

I was there for them

In the late 1990s, I was in my 20s, unmarried and living in London. I felt like this was a show aimed squarely at people like me. And indeed it was. This is what Friends is really about: that stage in your life when the most important people are your friends. Your friends are your ersatz family. Many times over, the opening theme song has The Rembrants singing the refrain “I’ll be there for you”.

Ross, Monica, Rachel, Joey, Chandler and Phoebe are living in Manhattan away from the families that raised them. And they’ve not started their own families yet. Or at least, they’ve failed to start families. It’s all there in the very first scene of the very first episode. Monica is talking about going on a date. Chandler recalls a dream in which a phone rings and it’s his mum – who never calls. Ross says his wife has finally moved out and is a lesbian. And then Rachel runs in wearing a wedding dress. She’s decided not to get married to Barry after all. Right now, she needs friends.

Rachel: …you're the only person I knew who lived here in the city.

Monica: Who wasn't invited to the wedding.

Rachel: Ooh, I was kinda hoping that wouldn't be an issue...

They are there for each other for the next ten years. And that’s what many of us are looking for at a certain stage of life.

A show as well-written and funny as Friends will always have appeal to a culture containing a significant proportion of ‘anywheres’. That’s the name given to the mobile graduate class by David Goodhart in his brilliantly observant book, Road to Somewhere, published in 2017. The ‘anywheres’ are those who leave the support of extended families at home (like the ones you’d see in The Royle Family) to study at university in a city in another part of the country, and then move to another city for employment. People in that situation need friends. Streaming episode after episode of Friends might give you that feeling, along with lots of beautiful people and some really good jokes.

Friends are Family

Some argue, however, that families are so fundamental to our society, that many sitcoms are essentially families when it comes down to it. This idea was broached by Mitch Hurwitz on Julie Klausner's podcast How Was Your Week. The creator of the sublime Arrested Development, Hurwitz said, "At one point I remember learning that there was this classic archetype of matriarch, patriarch, craftsman, and clown."[1] It’s not much of leap to map this onto a nuclear family of a mum, dad, older sibling and younger sibling.

In a British context you might explain the classic Porridge this way. Fletcher is the big brother to Godber, the naïve, goofy younger brother. The patriarch is the strict disciplinarian, Mr Mackay, whereas the gentler prison warden, Mr Barraclough, is the mother.

Friends contains all kinds of familial relationships, beyond Ross and Monica being brother and sister. Monica is like a big sister to Rachel, who needs to grow out of her sense of entitlement. Chandler is like a big brother to wayward Lothario Joey. Phoebe is like a strange, wise-but-crazy mother to them all. Ross is often the responsible, sensible dad telling everyone to calm down.

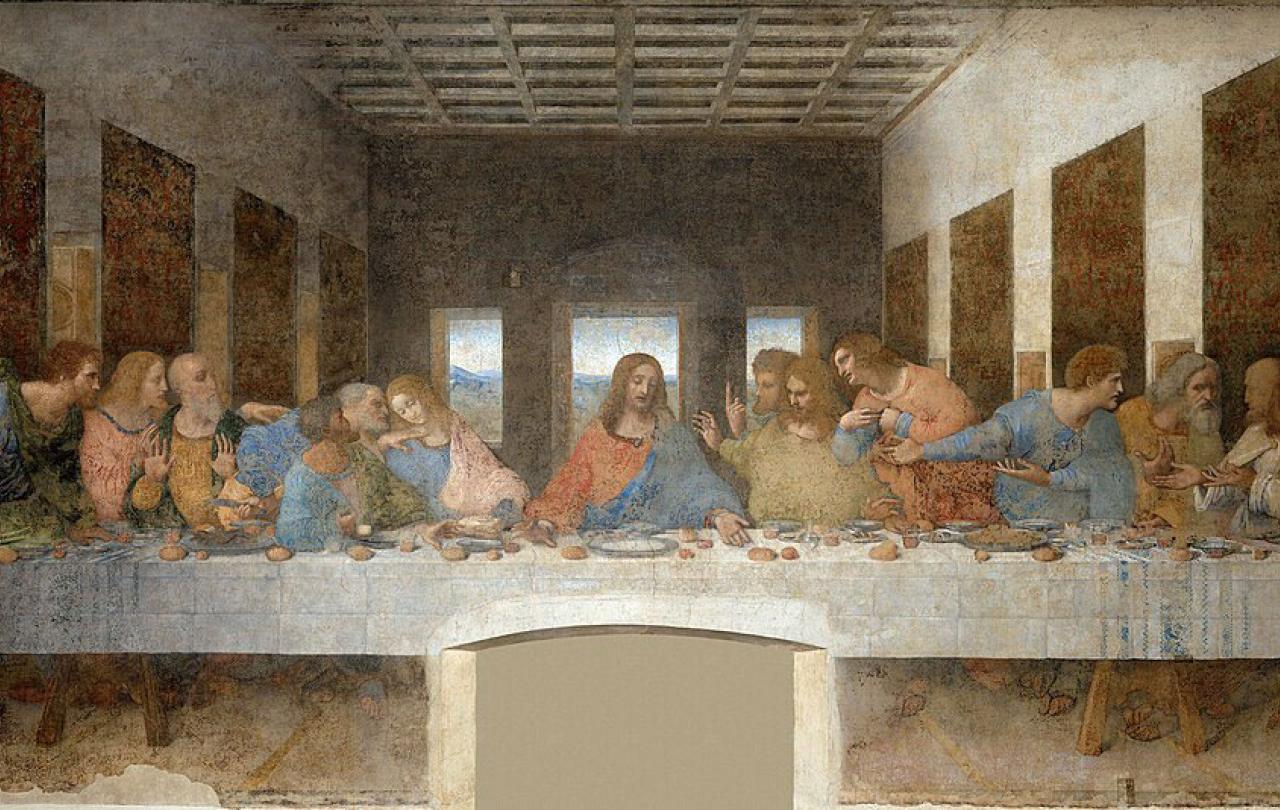

We shouldn’t be surprised to see these familial relationships around us. In Christianity, God is familial within himself, being Father and Son. He made the first man to be married to the first woman. Genesis, the foundational book of the Bible, is the original family saga, with siblings who fight and cheat – and kill. The stories create all kinds of patterns that aren’t just recognisable in sitcoms like Friends but in our own complicated lives and fractured families.

'We aren’t comrades, amigos or fellow worshippers. We are brothers and sisters. We are responsible for each other.'

In the New Testament, we read how Jesus walked among us, called his followers brothers and sisters. Christians still do that today. In the church, we aren’t comrades, amigos or fellow worshippers. We are brothers and sisters. We are responsible for each other. So when churches go wrong, it’s so painful and damaging because the relationships run much deeper much faster.

Even so, if you’re in a city, and looking for family support, you could do a lot worse than step into a church. Anyone who goes to church will tell you that it’s the oddest bunch of people replete with dated hairstyles from the 1990s with plenty of, frankly, unbelievable characters. It’s the Church’s best kept secret: community. A whole network of people who are there for you. After all we belong at home with family. That’s where Friends ended up in “The Last One", also known as "The One Where They Say Goodbye". Monica and Chandler are setting up home for the twins. Finally, Ross and Rachel are together and will surely be husband and wife. And Joey gets a spin-off. After all, it is show-business.