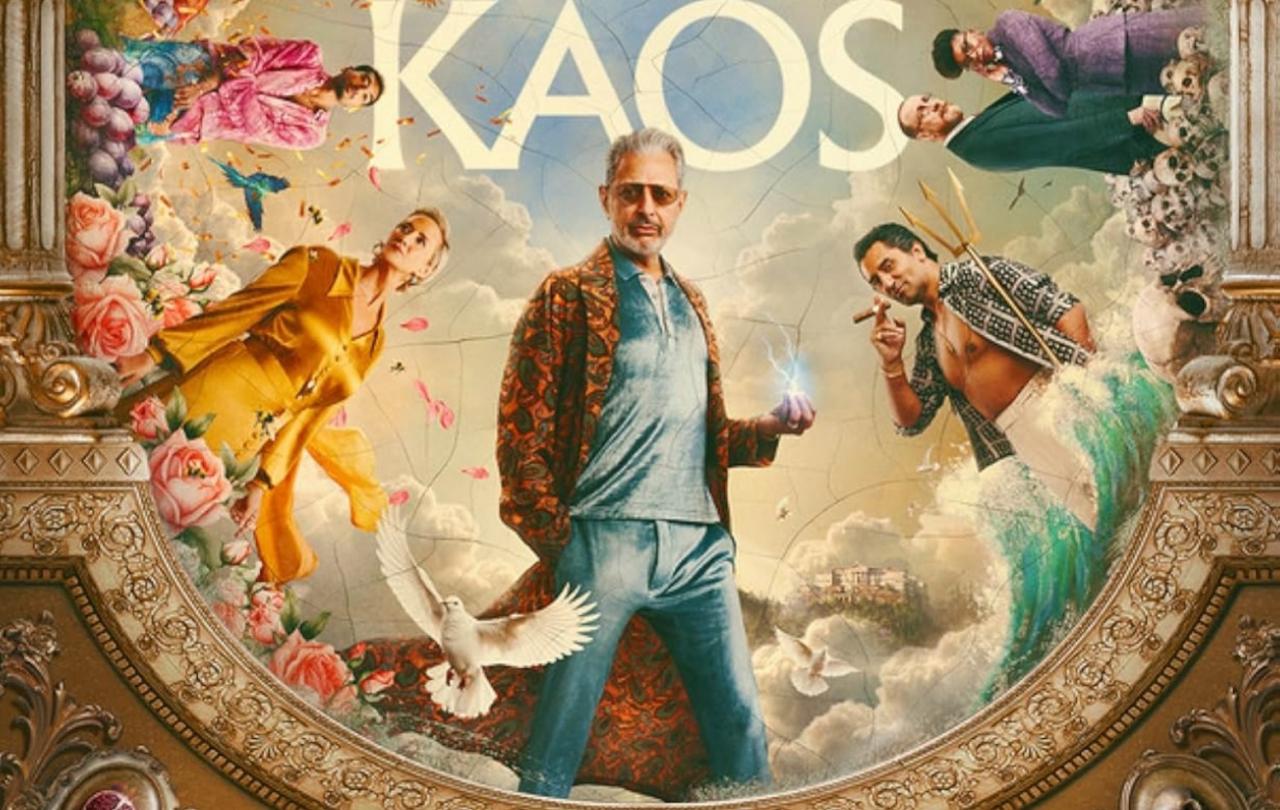

The old gods are making a comeback all across Western culture. This is a conclusion increasingly reached by a spectrum of culture-watchers; some religious, some not at all. But, if true, the boldest and brashest example of this comeback may well be the new Netflix series KAOS, starring Jeff Goldblum, released last month.

Kaos is a genre-busting mythological dark comedy-drama. One might say a modern re-summoning of the pagan gods.

Charlie Covell, the writer and mastermind behind the show, and a self-confessed mythology geek, has created a colourful, high production, and often funny depiction of what the world might be like if the gods of Olympus still ruled over us. The plot follows several different strands taken from Greek mythology - most obviously Orpheus’s journey into the Underworld to bring back his dead wife, Eurydice - and weaves them together into a larger narrative, retelling the downfall of the gods.

As the show opens, Zeus reigns as king of the gods from his fantastically kitsch mansion atop of Mount Olympus. So long as the sacrifices and adulation of humankind keep rolling in, he is happy. But when he wakes one day to discover a new wrinkle on his forehead, this triggers not only a kind of mid-life crisis, but also possibly - so he fears - the end of the world as he knows it.

Goldblum plays Zeus as, well, Jeff Goldblum: quirky, nervy, paranoid, and not a little menacing in an understated way. In other words, perhaps more “Jeff Goldblum” than you’ve ever seen him on screen before. It is certainly a compelling and sometimes hilarious portrayal.

“A line appears, the order wanes, the family falls, and Kaos reigns.”

This is the prophecy that has haunted Zeus for aeons. What he doesn’t know is that he shares this personalised prophesy with three other mortals in the story - Eurydice (Aurora Perrineau), Caneus (Misia Butler), and Ariadne (Leila Farzad) - all of whom will play an unwitting role in bringing about the overthrow of the world order under the Olympian gods (hence: KAOS). The early episodes establish who these mortals are and begin to draw their disparate stories together.

Counterpoint to Zeus is his brother, Hades, ruler of a literally black-and-white underworld, with David Thewlis brilliantly cast in the role as the world-weary and ailing keeper of the realm of the dead. Something is amiss down there which threatens the whole system of human souls and what happens to them. When he tries to warn his brother, Zeus’s disdain for Hades and his problems only makes matters worse. Also in the frame of this dysfunctional family are Hera (Janet McTeer) and Poseidon (Cliff Curtis) - brother and sister (and wife in Hera’s case) to Zeus, as well as being lovers behind his back, who are poised to put into effect their own betrayals, if Zeus goes too far off the rails.

Last, but not least, since he proves the bridge between the gods and humans is Dionysus (Nabhaan Rizwan), one of Zeus’s many children. (But the only one who comes to visit.) A hedonistic agent of chaos from the outset, Dionysus seems to be the only one of the gods with any genuine interest or admiration for humans. Impressed by rock-star Orpheus’s passionate love for his wife, Eurydice (“Riddy”), it is Dionysus who helps Orpheus break into the Underworld to get her back when she dies, thus triggering the series of events that could let to the fulfilment of the prophesy.

The illusory glamour of the gods of Olympus seem to titillate us once more. We don’t really believe in them, but we’d kind of like to see more of them all the same.

Smart, stylish, twisty and certainly original - (the entrance to the Underworld is through a dumpster bin around the back of a bar) - Kaos is an ambitious multi-stranded epic about power, fate, love, and family. But perhaps above all, it is saying something about the relationship between humanity and the divine. At one point, one mortal tells another that the only good things in life are human. This feels like a statement of underlying intent. And the way the gods (especially Zeus) become more capricious, more sadistic, more vengeful as the story unfolds, the more it feels like we’re encouraged to agree. Defiance of the gods is the real mark of virtue here. Rebellion against the gods, the natural outworking of that defiance.

The irony is that whatever distaste which Kaos succeeds in cultivating in us, the viewer, for pagan forms of the divine may help explain why, historically, Christianity swept aside all the pantheons of pagan worship of the first millennium in the wholesale way that it did. Jesus Christ literally incarnates that bridge between the divine and the human. And what’s more, the message he preached claimed that, far from disdaining humanity, God loves them so much that he was willing to be the sacrifice for their good. And not the other way round, demanding incessant and capricious sacrifice by humans instead.

Now, centuries later, in Western culture, familiarity seems to have bred contempt with that far more hopeful story. Instead, the illusory glamour of the gods of Olympus seem to titillate us once more. We don’t really believe in them, but we’d kind of like to see more of them all the same. And storytellers like Charlie Covell are only too willing to give the public what they want. If the old gods are indeed trying to make a comeback, Kaos shows us why we might think twice before inviting them in.

Does Kaos succeed? It certainly makes a valiant attempt to marshal a large number of plot lines involving a huge cast of characters, unfortunately not all of whom are interesting enough to keep you coming back for more. And an awful lot is riding on there being a Season 2 - that is, if the threads we have followed so far are to lead on into a satisfying and meaningful conclusion.

Without that, I’m afraid the whole thing may be left standing alone as a work of, well… chaos.