Reparations are in the news these days. Poland is demanding $1.3trillion from Germany for the destruction to their country by the Nazi’s invasion 84 years ago. The Mayor of New York City Mayor is advocating reparations payouts as a solution to the wealth gap between blacks and whites in the city, and Caribbean countries are considering approaching the United Nation international court of justice for legal advice about reparations for slavery.

In line with this trend, the Church of England intends to spend £100m on reparations for its past involvement in slavery.

As many have already pointed out, the receipt of any money from slavery profiteering was minimal and marginal at best, such that the rationale given for this intention involves a strange exaggeration of its own past faults.

The problem with this is that it implies a kind of boasting about its sins, which is itself a mode of sin, all too akin to the agreeable shudders produced when a supposedly repentant sinner details his past wrong doings before the altar. The greater the lapse, the greater the grace, in a kind of gross liberal parody of an already gross exaggeration of a more authentic Protestant legacy.

Why should the Church seek to do this? The answer surely is nothing to do with its reckoning with its own past shortcomings. It is rather the same old courting of middle-class respectability that has always afflicted Anglicanism at its worse, despite entirely opposite tendencies of which it can be proud. Reparations are fashionable in middle class circles and the Church wants to be in on the act. One should not mistake this for radicalism, nor for real repentance. If the West was really sorry for what it has done wrong in the past, it would not pretend that this wrong was not mixed up with a lot of good (in the case of overseas empires for example) but would seek in the present to act in an entirely different way: to abandon economic and ecological exploitation of the rest of the world in the present, and to seek to act always in a globally collaborative manner.

Rather than seeking to change the present, it is far easier to continue to condemn the past, which cannot seriously be undone.

The reasons it does not do so concern not only its continued commitment to an unqualified capitalism, but also and more subtly the truth that if we seriously wished to act positively and helpfully, we would have to resume some of our past paternalistic concern in a new idiom, that would no doubt prove unacceptable to a now liberal-dominated left. Increasingly, respectable liberal opinion cares far more about formal stances than about actual beneficent outcomes.

Rather than seeking to change the present, it is far easier to continue to condemn the past, which cannot seriously be undone. Financial compensation is itself a substitute for any real change of heart. For if we really regretted past exploitation, we would not continue to sustain it in a less involved and more purely economic, and therefore worse form today.

Furthermore, to imagine that one can set a price on damaged heads is only to repeat the quantification and monetarisation of humanity that was the logic of slavery in the first place. The fact that so many non-white people nonetheless back the call for reparations is only a sad proof that they are covertly locked into a capitalist logic and a liberal-rights thinking that tends to tilt over into the unchristian (despite Nietzsche) ethics of ressentiment.

Rather, one should say that our involvement in the Atlantic slave trade was so bad that nothing can offset it, save the sacrificial blood of Christ (recalling that he was betrayed for money) and our sharing in this atoning action through repentance and compensatory, embodied action in the present.

So why on earth would the Church of William Wilberforce and Trevor Huddleston feel that it needs to regret its supposed slave owning and racist past?

This was initially and most of all demanded and carried out by Anglicans of a usually High Tory persuasion, and though we should not forget some enlightenment opposition to slavery, which sometimes inspired the revolt of slaves themselves, it is an illusion not to consider this to be also Christian or at least post-Christian. After all, pagan republicans were not just at ease with slavery, they built their entire republican systems upon it. To a degree the United States tried at first to repeat that, till eventually a radical Christian vision (taking it beyond the qualified Biblical acceptance of slavery) won out in that country also, though it lagged in this respect behind Britain and the Anglican Church.

So why on earth would the Church of William Wilberforce and Trevor Huddleston feel that it needs to regret its supposed slave owning and racist past?

One might say that it is more important to feel shame and regret than to boast. But to celebrate one’s past saints is not to boast of oneself, but to accord honour where honour is due and to raise up admirable examples for admiration and imitation. To be human and to be creative in the image of God is continuously to praise as well as to blame, as the Anglican poet Geoffrey Hill frequently argued.

Moreover, if we only follow fashion in our blaming, which is also important, then we will tend to miss the more hidden and subtle culpable targets. Uncovering the latter is surely especially incumbent upon anyone claiming to follow Christ, who constantly located sin where it was unsuspected and inversely found hidden if suppressed virtue to be present amongst those publicly deemed to be sinners.

In reality our coming to see the Good is always the work of time and is always revisable.

But in the case of both praise and blame what matters most is to take the drama of past history as instructive: not to claim that we can finally undo its past injustices as past. This is blasphemously to appropriate the prerogatives of God at the last judgement and to newly extend the false logic of sacramental indulgences.

For a kind of unspoken presentism lurks behind the reparations mentality. The assumption is that we all really live in an ahistorical eternity within time, such that if we were always thinking rightly we would always see, in any time or place, the truth of current liberal nostra, despite the fact that they are themselves incessantly changing, for example with respect to gender and sexuality.

In reality our coming to see the Good is always the work of time and is always revisable. What the Greeks and Romans regarded as acceptable treatment of ‘barbarians’, women and slaves we can now see to be horrendous, and we are right to do so. And yet it would be a mistake to suppose that classical nobility was a self-delusion: by their own lights people in antiquity acted virtuously and in certain ways which we can still recognise today, with regard to fortitude, magnanimity, forbearance and so forth. We can also allow that they developed acceptable notions of virtue in general, even if they filled them with often highly questionable content.

In the case of the Bible, the notion that ethical insight changes with time is still more foregrounded than with the pagans. It is a record not just of backsliding, but of constantly new prophetic and visionary insights, culminating in the drastic New Testament revisions of what is ethically demanded of us all the time, even if this is often cast as return to lost origins. Yet despite this, the forefathers continued to be praised as well as blamed, celebrated as well as condemned, even in the New Testament.

In the case of both pagan and Jewish antiquity it was realised that even if we can claim to have surpassed our predecessors in insight, our new insights still depend upon their earlier ones, such that we stand upon the shoulders of giants.

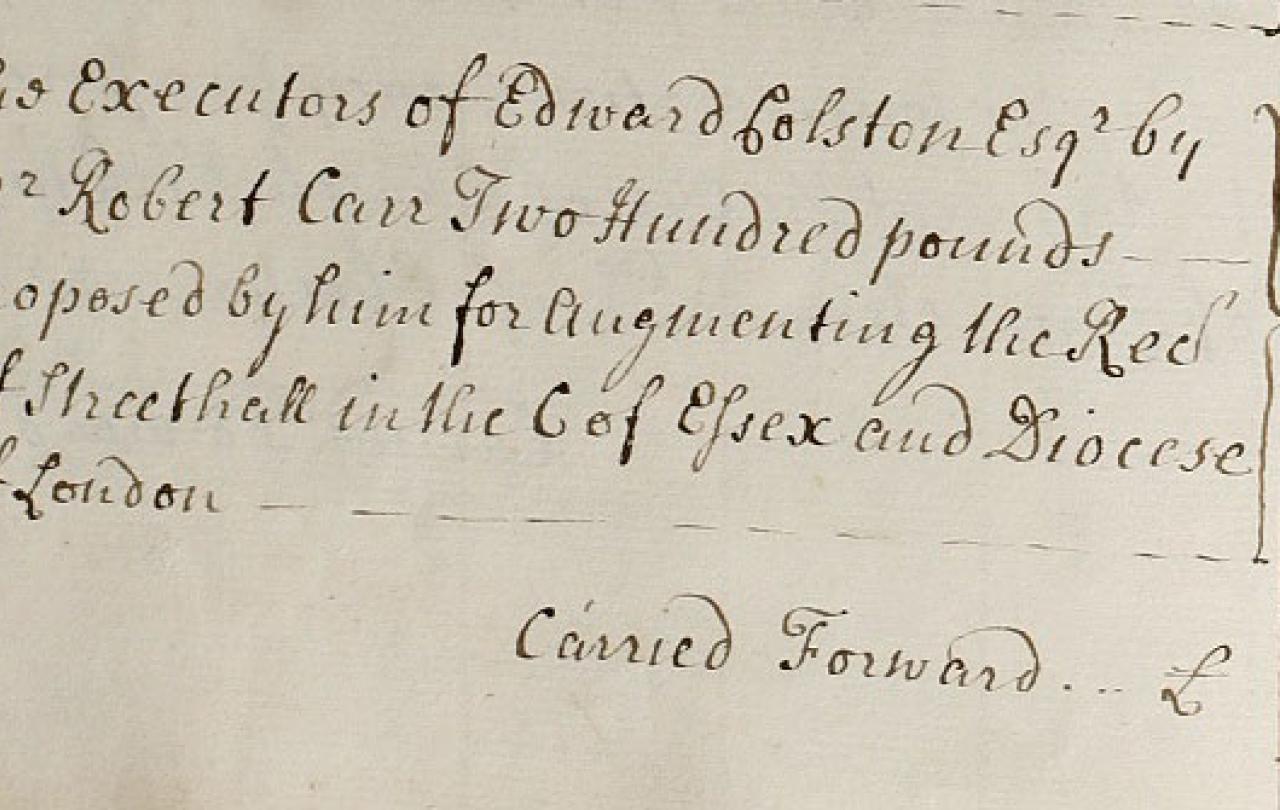

We have then no warrant to condemn people in the past who were good by their lights of their times, including benefactors like Edward Colston of Bristol who were also slave traders, and whose statues should therefore be left to stand. They were perversely blinkered indeed, but they lived in a blinkered age. It is pointless to blame them and more important to praise the rare visionaries who were able to think beyond this. One may say well ‘everyone could have seen the point if some did’ but this is to ignore the truth that most of us usually find such people awkward and that they have not always thought through an alternative way forward. After all, a failure of Northern abolitionists adequately to do that was in part responsible for the continued pervasive misery of African Americans through many decades and continuing today, after the American civil war.

Everything in time and space is infinitely ramified and ramifying. Absolutely everything is contaminated and yet the bad is interwoven with the good.

Another problem with reparations is, of course, the problems of identifications and the selectivity involved.

Just who are the current descendants of slaves and the continued legatees of disadvantage thereby accrued? All African Americans, of every class, despite much intermarriage? All the inhabitants of the Caribbean, again despite social hierarchies? African countries, despite past African complicity in, and indeed originating of, specifically modern slavery?

And then why only certain selected ethnicities? To focus on only black people looks candidly like supporting a will to power and a reverse anti-white racism. What about all women, and all gay people so mistreated in the past? What about the working classes in Britain whose children were sent down mines and up chimneys under conditions of dependence little better in practice than outright slavery? Are they deserving of compensation? After all, their ancestors are often readily identifiable by both family and region.

So wherever would one stop? Should Anglo-Saxons demand at last justice from the conquering Normans, since these different ethnic legacies are still somewhat identifiable by class, as anyone suddenly summonsed into the arcanum of old county money lurking within guarded private estates with unimaginably huge old trees, will readily testify.

Everything in time and space is infinitely ramified and ramifying. Absolutely everything is contaminated and yet the bad is interwoven with the good. If we start to try to break with all of the bad through a sort of Maoist cultural revolution (in relation to the British imperial past, for example) then we will end up losing the fruits and flowers as well as the tares and political terror will ensure that even only the most privileged weeds survive such a purge.

So, the Church of England needs to stop following fashion and lose its current obsessions with reparations, diversity, excessive safeguarding and all the rest of it. Instead, it needs to recover its genuine legacy of paradoxically conservative radicalism, nurtured at once by evangelicals and ‘liberal Catholics’, by radical Tories and Christian socialists. It is just this which can truly challenge the economically and culturally individualistic times in which we live, to the ruin of us all.

At home it needs first to set an example in its own backyard, by entirely reversing the current policy of parish destruction, which all the evidence now shows is partly responsible for Christian decline in this country and entirely cripples Anglican mission in all its dimensions. The more that the Church returns to a policy of putting sophisticatedly trained clergy in socially prominent and capacious parsonages (enabling hospitality discussion) within single or very small groups of parishes, then the more it can start directly to nurture rooted and genuinely inclusive communities, socially responsible enterprises and integrated local ecologies, beginning with churchyards.

This is where the church’s money should be spent: on substantial nurture, not questionable and futile gestures.

On the global scale, Anglicans need to turn from a presentist abolition of the past to a future-orientated preoccupation with the present. If our current way of living is everywhere destroying the planet, promoting ever more inequality and inhibiting human health and intellectual capacity, then surely the question to be posed is whether this is the result of abandoning past spiritual priorities?

Instead of mounting the liberal bandwagon of futile and counter-productive virtue-signalling, the Church of England should ask what an alternative ‘psychic politics’ based on a mixture of genuine hierarchy and participation would look like, and turn its energies towards supporting those already seeking to enact this.