The camera looks down over fields, the green and pleasant land of England far below. It moves slowly over the landscape until gradually it begins fly over the streets and parks of North London, past Wembley Stadium with its well-known arch, curving into the sky and back down again, and finally, as the urban sounds grow louder, it begins to home in on a small dark rectangular spot in the centre of the screen. As it gets closer, the familiar outline becomes clear. It is Grenfell Tower.

Today when you go past the Tower, just off the Westway, a major road artery into central London, the Tower, or at least the remains of it, is covered in white plastic sheeting. It’s a kind of compromise between those local people who can’t bear to look at it every day, and those who want it to remain visible as a stark monument to the injustice and greed that led to the fire that killed 72 people in June 2017.

Steve McQueen is a Londoner, a well-known filmmaker, Director of 12 Years a Slave and winner of the Turner Prize. As the plastic sheeting was about to go up to hide the grim nakedness of the Tower, he wanted to ensure the story of Grenfell was not forgotten, so filmed the building in January 2019 just as the ghostly shroud begun to creep up the side of the building. His remarkable film, simply called Grenfell, has been showing at the Serpentine Galleries in Hyde Park. He recently voiced dismay that few politicians had come to see the film, despite being invited. They really missed something.

As the camera revolves around the Tower, there is no sound, no commentary at all, as if there are no words to describe what happened here.

The camera homes in on the tower, and gradually begins to rotate slowly around it. We peer into the rooms of this tall, charred block, standing like a black cliff face, a literal tomb in the heart of London. Behind it, there is the gleaming shining face of the Westfield shopping centre, cars driving up and down the slick dual carriageway that flows past it, but the focus is relentlessly on the horror of the Tower in front of us. The camera goes round and round, occasionally drawing out, but then being drawn back in, mesmerised by the blackness, the darkness, the shell of the Tower and the ghosts of the lives it destroyed.

Watching it brings on a mixture of fascination and nausea. Nausea from the relentless circular motion of the camera. Fascination at the details – pink plastic bags of debris in what was someone’s living room; the remains of a kitchen cabinet that had somehow survived the inferno. And for me personally, as the Bishop of Kensington at the time, memories of being there on the day, watching the tower burn; talking and praying with dazed survivors, evacuated from the blocks around Grenfell; listening to firefighters with the agonising dilemmas of trying to reach the highest floors, with breathing apparatus that wouldn’t allow them to get there. As the camera revolves around the Tower, there is no sound, no commentary at all, as if there are no words to describe what happened here. We see into the flats that were once homes, with kitchens, bedrooms, toys and family mementos. We look into the haunting floors at the top of the tower in which many of the victims died, pushed upwards by the flames and the advice to stay put until help came, but of course none ever did.

It doesn’t annul the pain, doesn’t offer easy, facile optimism, pretending that the awfulness doesn’t matter. Yet it makes contemplating it bearable.

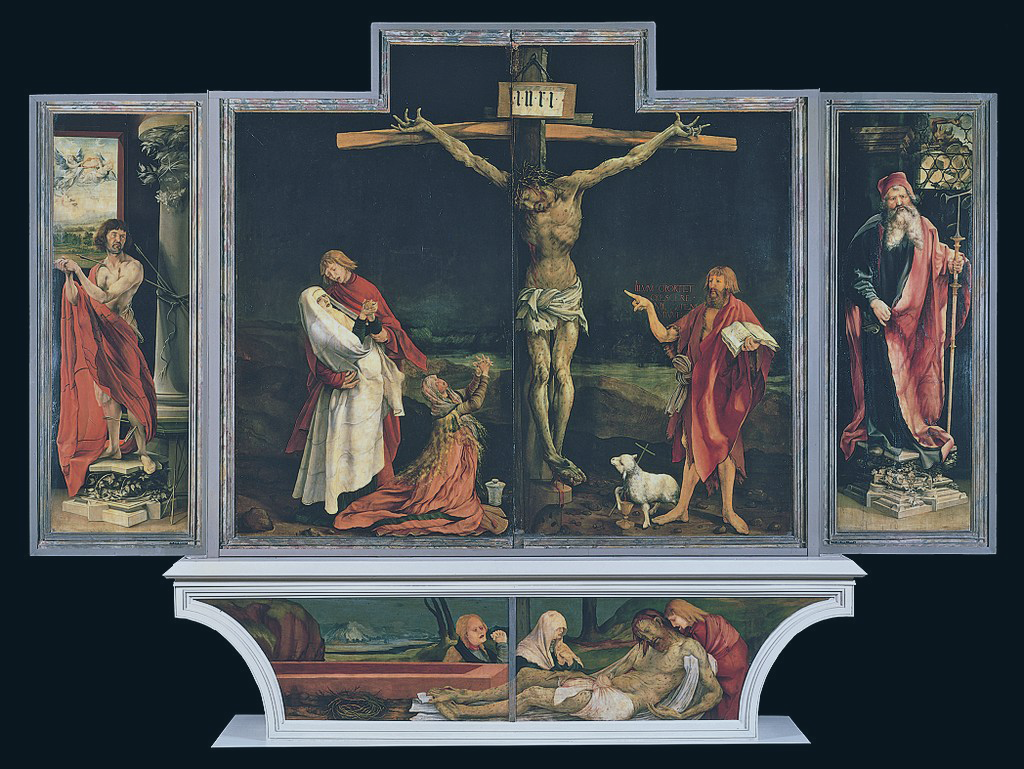

Watching the film reminded me of standing before a medieval painting of the crucifixion, such as Grünewald’s famous Isenheim altarpiece. Pilgrims would stare for hours at such paintings to bring home to their hearts and minds the consequences of their sins, and to help them resolve to live differently. We don’t do penitence well in our culture. This is a penitential film, and it’s what the politicians who didn’t turn up to watch it have missed.

Steve McQueen, just like Matthias Grünewald, wants us to look hard at the reality of what we have done - innocent life lost in the most horrific way. The altarpiece focuses on the intense suffering of Christ, the stretched sinews, the blood pouring from the wounds, the agony of those helplessly watching on. Just like this film that keeps your eyes fixed on the shattered shell of a building, the painting doesn’t let your eyes stray from the grim reality.

Yet there is a difference. Just faintly in the dark distance of Grünewald’s painting are the glimmers of dawn. On the horizon, the sky lightens, just a little. It is of course a reference to Resurrection, just around the corner. It doesn’t annul the pain, doesn’t offer easy, facile optimism, pretending that the awfulness doesn’t matter. Yet it makes contemplating it bearable. It allows you to focus on the revulsion, yet makes it endurable by offering the hope of Resurrection. And as Christian thinkers and pray-ers have insisted over the years, you only get to Resurrection through death, not by avoiding it.

At the time of the fire, I remember doing numerous media interviews with news outlets from across the world, with journalists hungry for some words to satisfy the global fascination with this tragedy. What could I say? What could possibly make sense of such a thing? I resolved that in every interview I would try to acknowledge the dreadfulness of what had happened, but also to strike a note of hope - that that despite what had happened, lives could be rebuilt, a community could find healing, then there was a road out of pain, one day, to peace – all because I am a Christian, and therefore have to believe that resurrection follows death.

Steve McQueen's brief film is compulsive watching. If you get a chance, you really should see it as something that brings home the horror of Grenfell more than anything I have seen. It is Grenfell’s Good Friday. Grenfell’s altarpiece. Watching it with Christian eyes, however, I kept looking for the glimmers of dawn.

Grenfell has been subject to a huge amount of commentary since the fire. There are those on the left who see it as a monument to corporate greed and capitalist rapaciousness. They demand Justice for Grenfell, which for many, means locking up or punishing the guilty. There are those on the right who see it a simply a dreadful accident that could have happened anywhere. One side calls it a crime. The other calls it a tragedy. Which was it?

The Left is perhaps rightly consumed with anger, demanding justice, legal convictions as resolution. Many on the Right look for a while, yet eventually avert their gaze, thinking it of it as one of those things, just an awful tragedy. I remember a Council official saying to me: “Well, one day, we just have to move on from Grenfell.”

What happens beyond lament? It is one thing to grieve those who died. It’s also something else to critique the failures that lead to it. Issuing prison sentences to the guilty may satisfy the desire for justice, but doesn't in itself bring about a new, hopeful, common life that renders simply unimaginable the pattern of moral compromise and sheer carelessness for the safety of others that led to Grenfell. On the other hand, simply consigning it to the category of awful accidents doesn't take seriously the grievous sins that led to the fire, and fails to give due recognition to the suffering of those who died.

Neither left nor right can offer us a sure way forward. That is where we are short of vision at the moment. An event like Grenfell easily falls off the radar of public attention because we don't want to look at it. Any maybe that is because we're not sure it will ever get any better. We need a way to keep looking at something painful until it is healed. That is the point of penitence - to go back to painful places in our lives to find healing. Yet you can only really do that if you believe healing can be found, that death ends in life, not the other way round.

The Christian story that holds together death and resurrection, Good Friday and Easter Sunday enables us to look at death and tragedy and horror full in the face as this film so eloquently enables us to do. It enables penitence to be hopeful, not hopeless. Yet, it also enables us to bear it, because alongside it, it says that there is a reality beyond both crime and tragedy, that is not just retributive justice but a deep underlying trajectory of the world that is headed for life not death.

Of course, the Resurrection is not a political solution. It doesn’t convict the guilty or dictate future housing policy, important as those are. But it points us to the deeper reality - that perhaps what we need today is not so much political but spiritual renewal. We need a deeper vision of life and death that gives us a reason to hope, that offers a future. We need a bigger story, a story that kindles hopefulness, that can stir hopeless hearts and the glimmers of dawn, even in the darkness of a world filled with so much pain.