Why do we go to festivals? It was something I contemplated at 4am while trying to stop a marquee from setting sail into the air during a quintessentially English late July storm. Thankfully we pinned it down, but sometimes it seems we can't get a handle on something until it's been taken away from us. Lockdown allowed us to indulge in some soul-searching about our appetite for summer festivals. A Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport select committee survey of 36,000 people showed that what people most missed about festivals during the pandemic was 'the atmosphere'. The atmosphere, much like that airborne marquee, is something difficult to put your finger on, but whatever it is, you do want to soak it up.

So, what contributes to that ‘atmosphere’? Harry van Vliet from the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences compared over 20 studies into motivations for festival-going. He distilled them into: escape, family togetherness, socialisation, and novelty. Other researchers, such as Rippen and Bos, cite realising significance, giving meaning and giving shape, and deploying, developing and maintaining competencies. As abstract and ethereal as our motivations are, at festivals we want to ram the tent peg into the ground, staking the opportunity to escape or to imagine the future. Why else would you endure discomfort, questionable cuisine and sanitation, queues and sleep deprivation? We endure little inconveniences because we have bigger thirsts.

Then there's the gap between what people hope to get out of a festival and what the organisers are aiming for. Spare a thought for those who booked onto the FYRE Festival, which promised ‘a new type of music festival that would ignite the energy and power of its guests’. Instead, they ignited fury, lawsuits, and six years in prison for the founder. The driver here was greed. If festivals are an immersive experience, what the festivalgoers unsuspectingly immersed themselves in was the sad fruit of that particular rotten orchard. Instead of the gourmet meals and luxury villas, the staff ate sandwiches in styrofoam boxes and guests who’d spent up to $100,000 to attend fought over a limited number of mattresses and tents. One legal document from a guest claimed guests were lured into ‘a complete disaster, mass chaos and post-apocalyptic nightmare’.

The performer, therefore, is like a prophet or a priest. We get to enter little portals to the divine.

We know if we’ve immersed ourselves in something more hopeful. I’ve spoken to several people who’ve been to Taylor Swift gigs, all still ‘buzzing’. Cities and countries keep reporting the bounce, the economic uplift they’ve all experienced from a Swift visitation. Deep down, at concerts and festivals alike we all probably know that we’re not there to ignite the energy and power of us as the guests, but to spectate the energy of the maestro at work. They are the ones who plumb the depths of creative introspection for us. They are the ones who concoct, via musical alchemy and a large support team, something reaching transcendence. If we can immerse ourselves in that, then, however fleetingly, all the inconvenience will have been worth it.

Festivals, therefore, are a pick-n-mix of artistry that we can come up close to. And therefore, the thought goes, their creative genius. Which is almost as elusive as the atmosphere of an immersive festival itself. Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of Eat, Pray, Love, says it was a mistake when we placed the human at the centre of the universe, and the pressure that comes from having to be a creative genius. In her 2009 TED Talk she spoke about Socrates believing he had a daemon that spoke to him, and the Romans believed that they had a ‘sort of disembodied creative spirit’ called a genius. The performer, therefore, is like a prophet or a priest. We get to enter little portals to the divine.

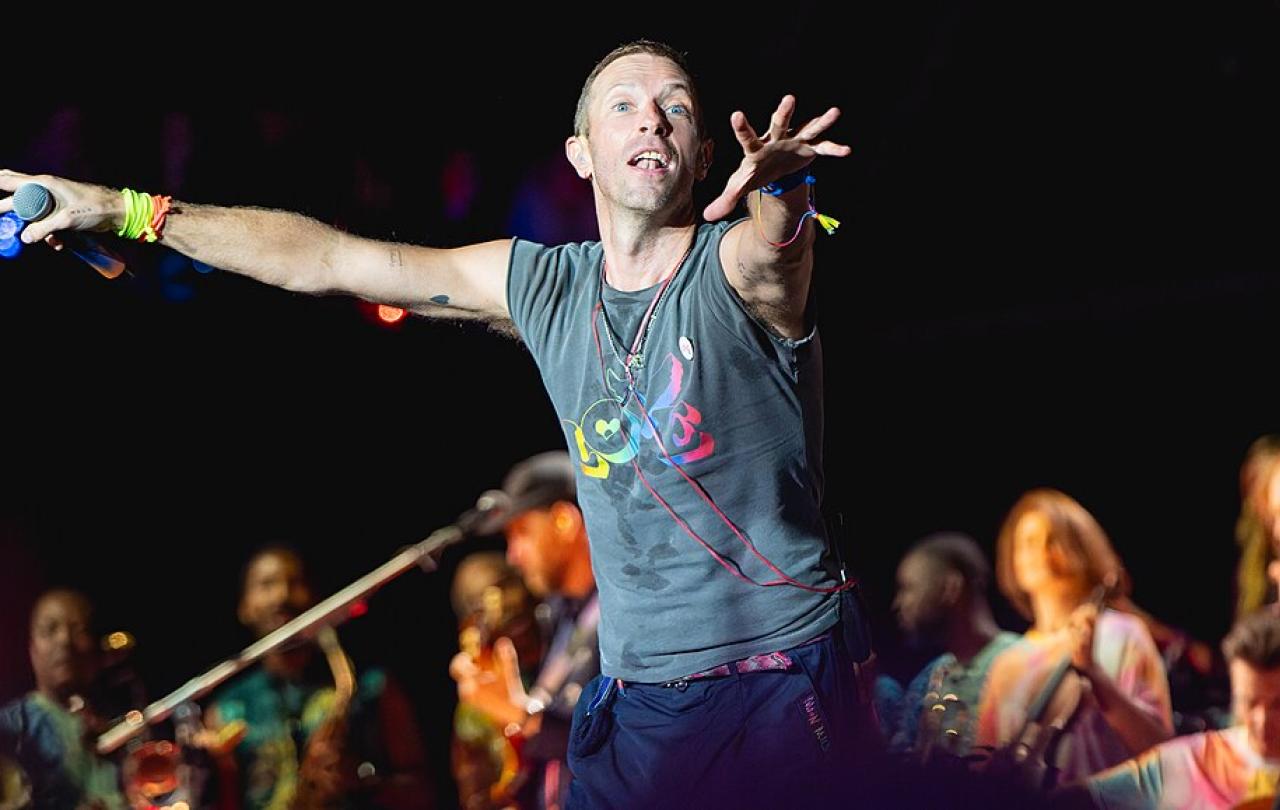

Maybe Coldplay can be right, when on the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury they sang to tens of thousands, ‘you’ve got a higher power.’

But what if the founder of the FYRE Festival was actually right? What if the guests themselves at festivals have energy and power, and not just Chris Martin? Millenia ago, this idea was once also floated at the festival of tabernacles, or Sukkot, where the Israelites made a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem and would camp in tents for seven days.

The gospel writer John says that Jesus spoke to whatever it was people had pitched up tents by the temple for:

‘On the last and greatest day of the festival, Jesus stood and said in a loud voice, ‘Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them.’

John goes on to explain that ‘By this he meant the Spirit, whom those who believed in him were later to receive. Up to that time the Spirit had not been given, since Jesus had not yet been glorified.’

Where the Holy Spirit had previously been given to specific people, for specific times and purposes, including creativity, here the Holy Spirit was promised to anyone who would believe in him. And as well as their own fulfilment, the divine creative energy would flow through them to others.

More than a mere atmosphere or nebulous spirit, Jesus claims to be one with the creative energy who hovered over the waters at the start of the Bible, the dwelling place at the end of the Bible where God will be with his people, and drove a stake, or a cross, into the ground to enable this to happen.

Maybe Coldplay can be right, when on the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury they sang to tens of thousands, ‘you’ve got a higher power.’