My name is Stefani. I was a committed atheist for almost my entire life. I studied religion to try to figure out how to have spiritual fulfillment without God. I tried writing books on spirituality for agnostics and atheists, but I gave up because the answers were terrible. Two years after completing my PhD, I finally realised that that’s because the answer is God.

Today, I explain how and why I decided to walk into Christian faith.

Here at Seen and Unseen I am publishing a six-article series highlighting key turning points or realisations I made on my walk into faith. It tells my story, and it tells our story too.

I spent the first thirty years of my life looking for ways to have spiritual fulfillment as an atheist. I even got a PhD studying theology trying to figure out how to get the same peace and joy my religious friends had without believing in God.

For a brief period after finishing my PhD I thought I might have found some solutions. I tried writing books about them titled things like How to Have an Existential Crisis and Agnosticism: The Real Spiritual Truth and Joy. But they were not good books. When I shared this opinion with my friends, they all thought I was being too hard on myself. But I knew the truth: the answers I was providing just weren’t good enough. They didn’t make me feel happy or peaceful. Why would they work for anyone else?

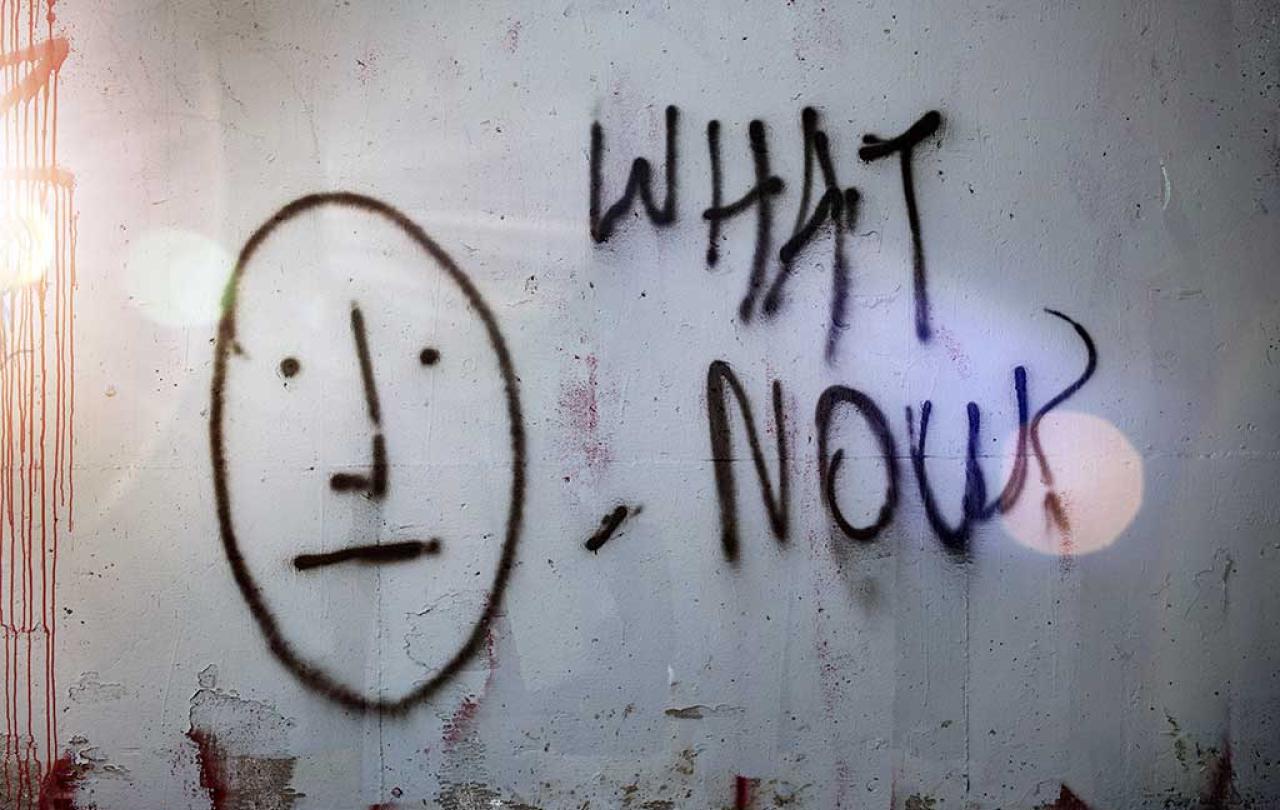

I had one last resort to try: giving up, which is the advice most atheist philosophers provide. According to them, happiness lies not in finding the meaning of life, but in accepting that there is none. Relax, they say. Stop searching for something that isn’t there! Be a good person. Enjoy the present moment. Be here now!

I decided to give it a try—and I really did try my best. I got a prestigious job. I rented an expensive apartment with a balcony overlooking Harvard Square. I bought a brand-new car and paid an extra $600 for a special-edition paint colour. I partied a few nights a week. I meditated every day. I cultivated friendships. I dated. I went hiking and sat on park benches and wondered at the beauty of nature.

Everyone who followed me on Instagram thought I was having the time of my life. But I have never been more miserable.

“Be here now” reduces meaning and possibilities for spiritual fulfillment

Of course, there are beautiful aspects to being present. It is true that being aware, mindful, and grateful in each moment enriches life.

But when that’s all there is, you run into three big problems.

1: Meaning is flimsy

All religions offer meaning that has what Donald Crosby calls a personal-cosmic link—that is, a way to explain our personal stories in terms of a bigger, ultimate story. These stories call us to be the best versions of ourselves for the sake of something beyond us. They give us reason to actualize. They provide solace when we falter or suffer. They offer meaning that is fulfilling, reliable, and concrete.

In contrast, when meaning exists only in the here and now, it’s not out a real thing out there to be discovered, but only something you can make up if you feel like it. Such meaning is flimsy, easily transgressed, and forgotten.

2: The universe is a cold, empty, meaningless void

Believing in God or some transcendent source turns existence into what William James calls a thou. Humans are naturally social beings and always in relationship. Being able to have a relationship with the source of all existence adds great potential for love, awe, adoration, belonging, and homecoming to life. In contrast, when the present moment is all there is, the universe is a cold, empty, meaningless void you just bumble along in until you die.

3: Life is unsatisfying, pain harder to bear, and effort more difficult

“Why bother?” is a common refrain in modern culture. There are many reasons, including unjust systems and corrupt institutions. But one major reason is that living only in the here and now traps what counts as “good” and “evil” in the here and now, too.

The highest good can only ever be pleasure (things like ‘flourishing' and 'well-being' are measurable only by how good they feel), and the worst evil can only ever be pain (suffering and injustice are similarly measurable only by how bad they feel).

Pleasure, however, never lasts. Dopamine, the neuromodulator that creates a feeling of satisfaction every time you obtain something you want (a meal, an achievement, a date with a crush), falls right back down after you get it, typically to levels lower than when you started. No matter how much you love, or how hard you party, or how much you sacrifice to help others feel good, you (and they) end up in the same state of longing you started in—or worse.

The only solution is to keep pursuing more pleasure. Many fall prey to all sorts of unhealthy attachments such as to substances, sex, and entertainment. Personally, I was most attached to professional success, food, and romantic love. I kept chasing ultimate satisfaction—while realising more every day that it was never going to come.

Pain, the greatest evil, is unavoidable. It can never be overcome. This makes us its victims, “helpless cogs in a cruel machine,” as Tim Keller puts it. This can create a victim mentality as well as a sense of futility, as there is nothing you can do to escape it or give it meaning. Many consider it their purpose in life to fight pain, but as none of us can ever put a significant dent in it, such efforts can feel pointless. Personally, I felt hammered by successive loss and the absurdity of injustice. I had no way to cope other than to escape with pleasure or to numb myself.

Back to the drawing board

Living in my sky rise apartment overlooking Harvard, I would often make a cup of tea and go stand on the balcony. I’d stare off into the horizon, my heart thudding dull and sluggish in my chest, and wonder: is this all there is?

It had been more than twenty years since the first time I read a book on philosophy and started my lifelong quest for spiritual fulfillment without God. I had remained hopeful that I would find an answer. And if there wasn’t an answer to be found, I would create one.

But as I sipped my tea and watched the sun slip below the horizon, night after night, I began to suspect that I was going to fail. I had just tried the most popular advice given by the most esteemed atheist philosophers and came up empty handed.

After just nine months, I pulled the plug on the experiment. A professor in France had recently published a paper on atheism I found intriguing. I terminated my lease, quit my job, and hopped on a plane. Two days later I dropped my books on a desk in the university bibliothèque and settled in to keep learning.

Little did I know, the program of research I’d given myself wasn’t about to deepen my understanding of atheism.

It was about to lead me to the one place I never thought I’d end up: in the loving arms of God.