Does it matter who tells the story of a place? It’s a question I’ve sat with as a writer, a community worker, and as someone who returned to my native West Country after a long time away. My departure and return to this place brought with it a sharper awareness of the labels this rural region could invite; of the way its people could be portrayed; of how easily they can be reduced to a one-dimensional stereotype that fosters little understanding.

And I am both reducer and reduced. I am a proud Devonian, rooted in soil thick with my ancestors, whilst also craving the culture and variety of elsewhere. My story of life in this place is complex. It’s a story that’s mine to tell, and not representative of anyone else from here – just as the people I’ve worked with in communities here and across sub-Saharan Africa taught me too: this person is not this place. This story is not this people.

Stories matter – stories told; stories hidden. They shape our identity, our opinions, our possibilities. John Steinbeck wrote that:

“A man who tells secrets or stories must think of who is hearing or reading, for a story has as many versions as it has readers. Everyone takes what he wants or can from it and thus changes it to his measure. Some pick out parts and reject the rest, some strain the story through their mesh of prejudice…”

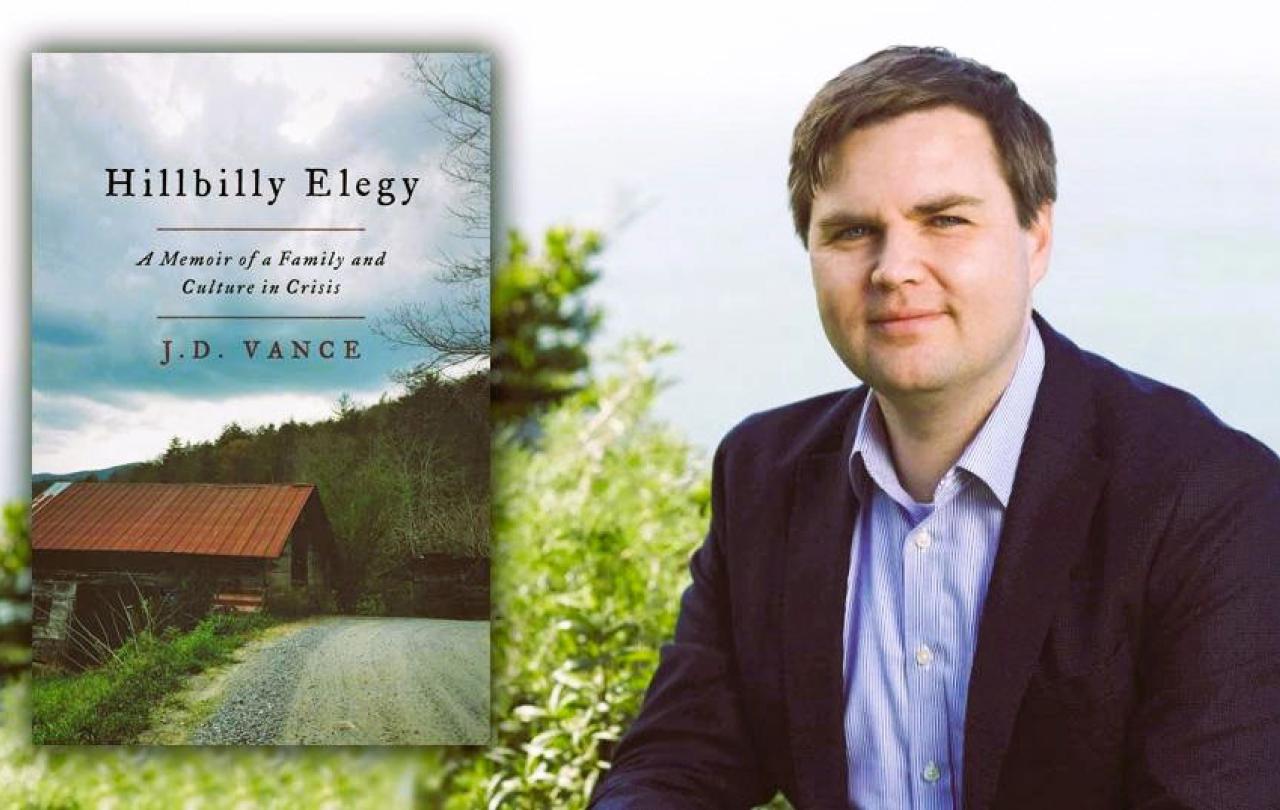

Stories told reflect stories carried, like light refracted through a prism. A story’s colours tell us something about who tells the story and how they see the world. Which is one reason perhaps that JD Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis came under scrutiny, especially since he was named Donald Trump’s vice-presidential running mate in the forthcoming US election.

Hillbilly Elegy tells the story of Vance’s white working-class family, from his grandparents in the Appalachia region of Kentucky to his own coming of age in Middletown, Ohio. Vance raises questions about how local people, including his own family, are responsible for their own misfortunes, including poverty and addiction. His book came out in 2016, at just the right time to give many Americans an insight into why so many people like Vance’s relatives and past neighbours had voted for Donald Trump. It was painted as the voice of a forgotten community, and it became a bestseller, admired by some for its portrayal of Appalachian culture by someone from the inside. But reading people who know the places he talks of, it becomes clear that the book is “rife with stereotypes and classic Republican talking points peddled under the guise of lived experience,” as one commentator said.

Sarah Smarsh, author of books including Bone on Bone: Essays in America by a Daughter of the Working Class, said in a Guardian piece published in 2016,

“that the media industry ignored my home for so long and left a vacuum of understanding in which the first glimpse of an economically downtrodden white is presumed to represent the whole.”

A Bitter Southerner article responding to Hillbilly Elegy said that generalisation means that “…complexity gets simplified, the edges get rounded out[…]Appalachia has been written about and photographed in such a compelling (if fabricated) way that the descriptions of passersby took on more weight than the lived experiences of the people being described. What remains is a concept of a place that is both wildly romantic in its natural beauty and backward enough to justify the destruction of that very nature.”

We live in divided times, but often I find it hard to discern real division versus the media-created story of division. Theirs is a story that gets things wrong. Smarsh reflects how “countless images of working-class progressives…are rendered invisible by a ratings-fixated media that covers elections as horse races and seeks sensational b-roll. This media paradigm created the tale of a divided America…” This is why it matters that we hear stories that do not fit that paradigm. A many-voiced 2019 publication Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy offered some of those stories in response to Vance’s painting of Appalachia.

Vance thought he could write the story of a 13-state region, but many Appalachians were unhappy about him becoming their spokesperson, especially when he seemed to blame the poor for their poverty. Appalachian Reckoning is a graceful counter to this: not silencing Vance’s own story but offering many more views and stories from Appalachia. Its co-editor Meredith McCarroll said she wanted to “complicate any singular view simply by including multiple ones. I wanted to create a chorus of voices, “each singing what belongs to him or her and to no one else,” to borrow from Walt Whitman’s view of place.” The publication offers cultural nuance, emotional connection, and a “context for some of the claims Vance makes in his book when it moves beyond memoir, and to pass the mic to a wider range of writers, poets, photographers, activists, and artists who make Appalachia a place far too complex to capture and far too dynamic to die.”

This approach feels important now, in the world as is it, with a media that often overlooks nuance, and with a culture that has become so visual that the way things are styled and framed and presented to us online can often be quite different to the reality. It is important to know the difference, and stories can help us discern that.

This symphony of existence can, if we give each voice its space, subvert paradigms of division and fear.

There are stories that are easy to peddle and easy to buy into. In charity work, I saw how the story of the benevolent professional outsider could shape things, leaving little room for local stories and experience. In politics I saw how the story of opposition got in the way of all the people getting on with the everyday work of restoring and caring for their communities across lines of difference. We can, unknowingly, make a place and a people shrink or even disappear with the stories we carry or amplify, or ignore.

Stories wielded unwisely can shrink faith as well as people and places. The Jesus who I did not grow up with but came to know slowly as an adult is a Jesus of nuance, compassion, and deep listening. He would not, I think, recognise the brand of Christianity that can be used to justify particular politics. That religion and politics have in places become so intertwined is perhaps a reflection of the reduction of the vastness of the Bible and the many diverse voices it contains into one story that serves a particular group of people. Jesus again and again subverted what empire and hierarchy and tradition expected of him. He invited people into his story over and over, curious about their own story but never using it as a reason to include or exclude.

When I think about who tells the story of a place – or of a people, a time, a faith – I see that really, there is never one story anyway. There is a chorus of voices, each a little different, each part of a vast harmony that – if we have the ears and heart to hear it – sings a song of challenge and joy, of despair and illumination. Former US president Woodrow Wilson said, “the ear of the leader must ring with the voices of the people”. Storytelling is not about giving people a voice – something I heard a lot in charity work. It is about listening to what they’re already singing. This symphony of existence can, if we give each voice its space, subvert paradigms of division and fear, of biased framing and selective storytelling. It can sing us back to ourselves, helping us see each other. And isn’t that what softens hearts, isn’t that why we tell stories? Author Kazuo said in his Nobel acceptance speech that “stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. Can you understand what I'm saying? Does it also feel this way to you?” Stories are not tools of manipulation or power, but pathways to encounter, to relationship, to understanding. They are, perhaps, the only way through divided times.