If Christianity is right, are all other religions wrong?

What is a Christian way to think about other religions? In the first part of this series, we established that there is no neutral standard or standpoint, and that we must always judge religions in light of some ultimate truth-commitment, even if for some that is only oneself. We must give up any pretence at the possibility of objectivity, or else we would be guilty of self-contradiction. Therefore, what I am now going to offer is a Christian approach to religious pluralism, with the caveat that it is not the only possible one and many Christians may disagree with it.

To be a Christian means to make Jesus Christ the ultimate standard of judgment and the light by which to discern truth from falsehood, good from evil. Jesus said, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me’ (John 14:6). Paul concurred: ‘there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and humankind, Christ Jesus’ (1 Tim 2:5). In other words, Jesus demanded absolute and total allegiance, and claimed to be the ultimate source of truth and spiritual guidance. He did not claim to be merely another wise teacher like Socrates, Confucius, or Mencius, whose sayings are followed because they make sense to the listener or because of the reputation of the speaker. Jesus wanted, not just to offer wisdom, but to invite us to leave everything and follow him, to submit to him as our master above all other masters.

Some people think that Jesus’ claim to ultimacy means that to follow Jesus means to believe all other religions are wrong. But this is a mistake.

The first point about this claim of Jesus is that it is far from strange or unique. The founder of every major world religion made similar claims about themself as the ultimate guide to truth. For example, Sri Krishna said, ‘I am the goal of the wise man, and I am the way. ... I am the end of the path, the witness, the Lord, the sustainer. I am the place of abode, the beginning, the friend and the refuge. ... If you set your heart upon me thus, and take me for your ideal above all others, you will come into my Being.’ Similarly, the Buddha said, ‘You are my children, I am your father; through me you have been released from your sufferings. ... My thoughts are always in the truth, for Lo! my self has become the truth.’ If Jesus had not claimed ultimacy for himself, he would not have founded a religion the way I am using the word (recall in the first part of this series, where I defined a religion as one’s commitment to what is ultimate).

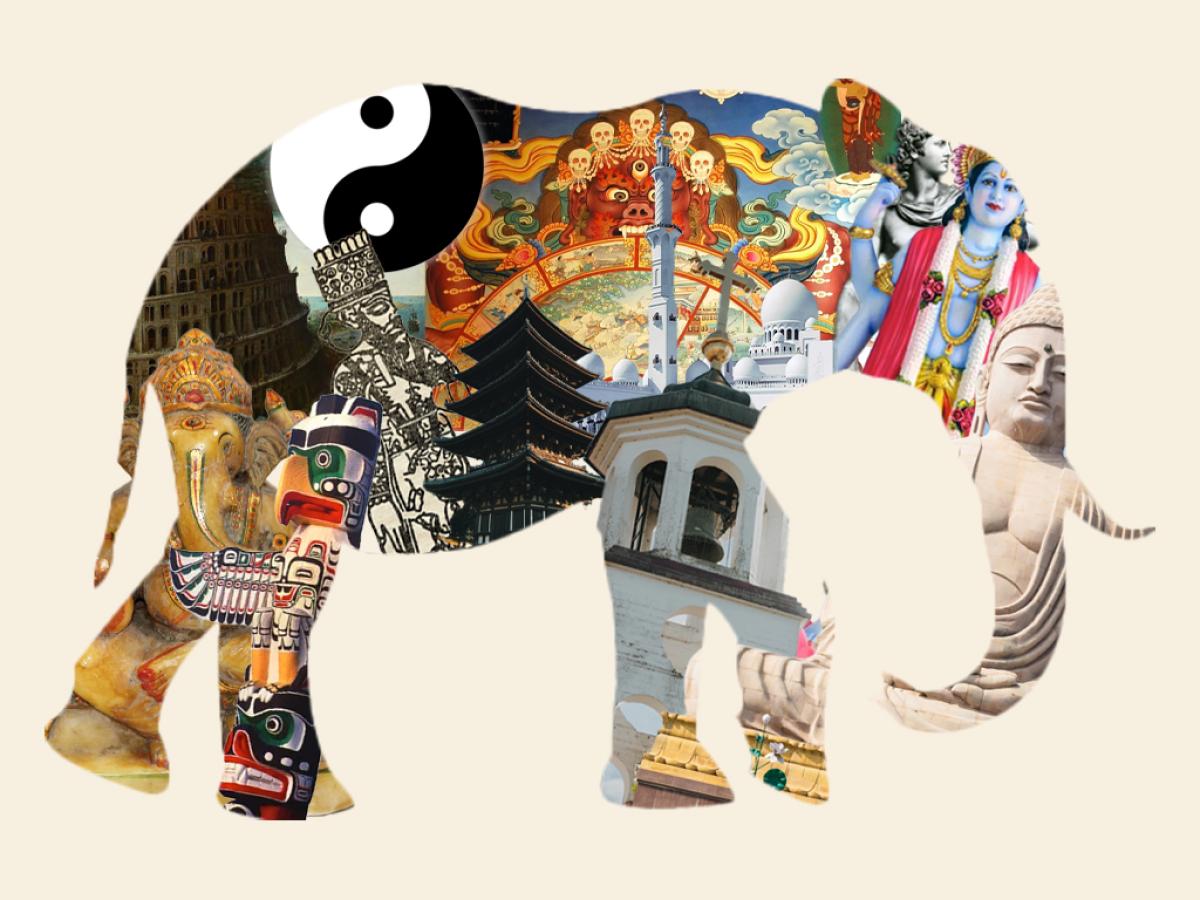

Some people think that Jesus’ claim to ultimacy means that to follow Jesus means to believe all other religions are wrong. But this is a mistake. Jesus is claiming, not that you can find truth nowhere else, but that he is the ultimate authority or paradigm through which we view the world, to help us see what is true and what is false elsewhere. If Jesus is the truth, this in no way implies that every other religion is all lies or wrong from beginning to end. How could they be, when they agree on so much? It is a strange feature of the modern way of thinking that it loves to posit radical ‘either/or’ alternatives, without seeing the overlap, the layers, the inclusiveness of one thing in another, and the deeper synthesis which reconciles surface-level contradictions. A Christian perspective does not require believing that other religions are lies, but that they only have part of the truth where Jesus has it all. There is all the difference in the world between believing a lie, and believing only part of the truth. Let’s consider some of the other world religions. For a start, to be a Christian automatically implies agreeing with Judaism on a huge amount. Insofar as Judaism denies Jesus as the Messiah, there is a conflict. But this is not a positive belief of Judaism, only an absence where Christianity claims a presence. Similarly, for Christians to consider Islam ‘totally wrong’ is a massive failure of perspective, an inability to notice the enormous overlap Christians have with Muslims, not only on the One Transcendent Creator God, but on all kinds of ethical issues, prayer, worship, fasting and so on. Something similar applies to Hinduism, which is often mistakenly considered polytheistic only because of its reverent denial of the conceivability of Transcendence, from which some Christians would do well to learn. To notice first what we disagree on and let that obscure all the common ground is a failure of charity and graciousness, which makes it a fundamentally unchristian attitude.

There is all the difference in the world, as well, between calling Jesus the truth and calling Christianity a complete explanation for everything, as if Christians understood Jesus completely and had nothing more to learn. To believe in Jesus is not to understand even Christianity in all its fullness, let alone the ways in which Jesus is manifest dimly through cultures that have never heard of him, or who have heard of him only as a symbol of Western imperialism. St Paul says that for Christians, Christ is ‘before all things, and in him all things hold together’. That means everything has contact with Christ simply by being a thing, by existing. The apostle John writes: ‘All things came into being through him [the Word], and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people’. So if anyone has life, they have their being in Christ, and the light of Christ reveals at least some truth to them.

For Christians, Christ is the fullness of the truth, and all else is only part of the truth. But Christians still have only part of the truth, because their knowledge of Christ remains incomplete and imperfect. Why could another religion not reveal something of Christ, as long as it didn’t contradict the trusted revelation of Christ in the Bible? How would we know, unless we took the time to listen and learn about other religions, without fear, without defensiveness, without needing to prove things or score points in an argument, also without compromising the ultimate authority of Christ as the supreme judge? Throughout the history of Judeo-Christian religion, the true insights of ‘outsiders’ have been accepted and become part of the faith of ‘insiders’. The Bible’s Book of Proverbs has chapters 22-24 lifted from Egyptian literature. The ideas of circumcision, a sacred temple, and a divinely appointed king all originated from practices in the surrounding nations, adopted and sanctified by Israel. St Paul quotes Greek poets as speaking truth about God. Justin Martyr recognised truths taught by Plato which enlarged the Christian understanding of God and the world. His maxim, “all truth wherever it is found belongs to us as Christians,” summarises the generous attitude Christians ought always to have in their search for wisdom and truth, without ever watering down the fullness of the truth in Christ.

True tolerance, as John Dickson puts it, isn’t the easy acceptance of every viewpoint but the noble ability to love those with whom we deeply disagree.

Concluding thoughts for those on a journey

We cannot expect all religious people in the world to come to agreement quickly and without great labour of understanding, love, and forgiveness. In the meantime, I propose the following attitudes for everyone, whether Christian or not, who acknowledges their own limited and non-objective perspective and yet is serious about the quest for ultimate reality.

Provisionality: faith is a journey, truth is a destination. To call it ‘faith’ means that it is not certain, that it is provisional, that it can grow and change. Everything you believe is always provisional. Never say ‘I will never change my mind on this’ because you do not know the future. This is particularly true for Christians. Rowan Williams describes Christianity as a basic life commitment which one takes before having all of the facts and evidence. In other words, to be a Christian means to be betting your entire life that following Jesus is the best way to live. You can’t prove this, you can’t be certain of this. You can’t even evaluate its likelihood from any neutral or objective standpoint. But you only have one life, and how you spend it will be your bet.

Authenticity: live your beliefs to the max. That is the only way you may find them to be false, or the only way others will be attracted to them if they are true. Much of the confusion in the world is a result of hypocrisy. Do not add to it. Learn also to articulate your own beliefs clearly to yourself and others. This means getting to know them by diligent study.

Empathy: learn to see the world from other points of view. In 2017 the world’s top religious leaders issued a joint appeal: “make friends with followers of other religions.” Some people say there is too much talk and not enough action in the world. I say there is not enough real dialogue, not enough listening, which implies someone is talking. No harm can be done to anyone’s faith by listening, seeking to understand, not prejudging. And for Christians, it is a requirement, not an optional extra, because it is the basis of love. True tolerance, as John Dickson puts it, isn’t the easy acceptance of every viewpoint but the noble ability to love those with whom we deeply disagree.

Hope: the truth gives itself to be known. The universe does not fundamentally lead astray those who seek the truth with all their heart. This cannot be proven. That is why it is called hope. But certainty is not a luxury granted to anyone. You only have a choice between hope or despair, i.e. hope or its absence. Neither option makes more rational sense than the other, yet as life-attitudes they pervade your every choice and belief. Which one will you adopt as your own?