Transformer is a fun book. I don’t mean to sound trite, or to damn with faint praise when I say that. I mean it. Transformer is a fun book, and frankly too many books I read aren’t fun.

David Foster Wallace used to say something similar (yes, the same David Foster Wallace whose novel Infinite Jest is over a thousand pages and has actual honest-to-god endnotes): much of contemporary print media has lost its ability to be fun. And isn’t that what we’re in this for anyway?

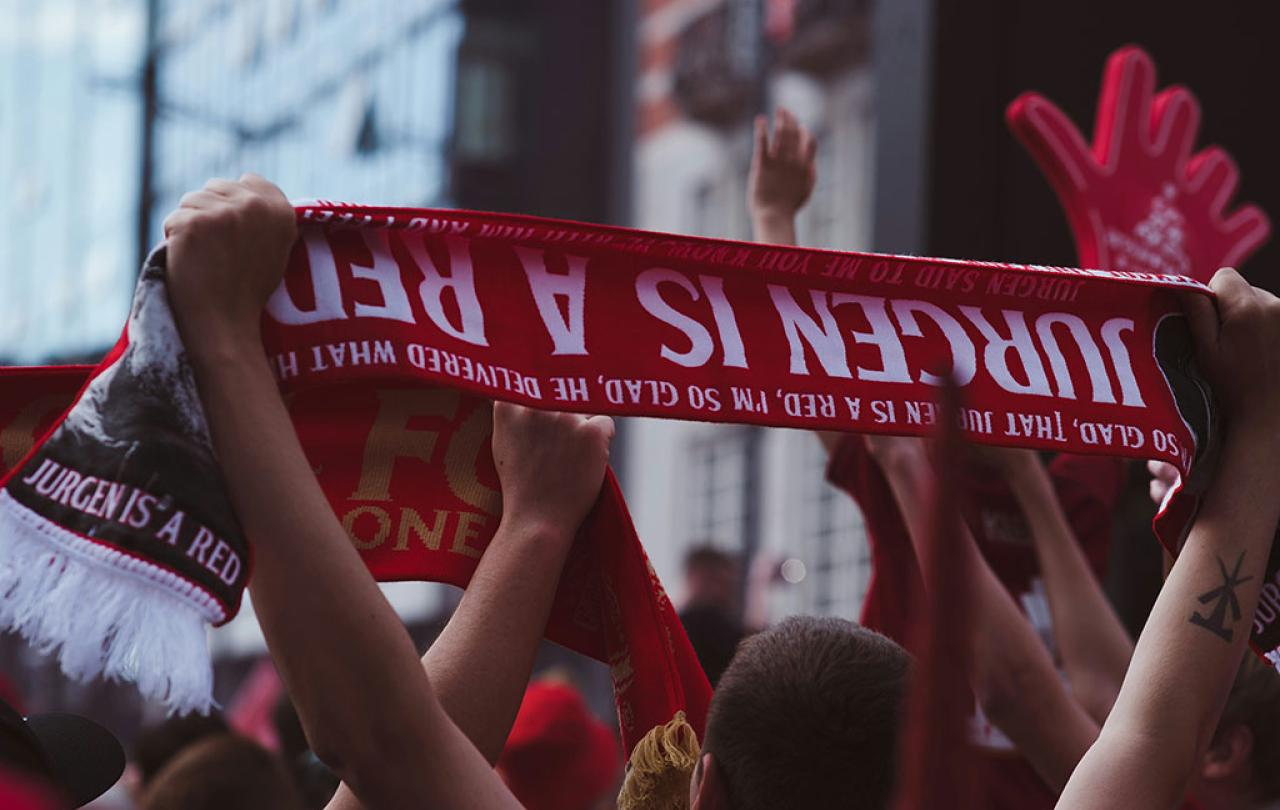

And that is, I think, why Transformer feels like such a relief, honestly. None of the trademark scouse humour and levity that has made The Anfield Wrap such a successful and appealing football podcast is lost in the transition to text. It is a funny book. It is a fun book.

Of course, there’s a lot here that you might expect to find in a book about Klopp, too, like discussions of key games throughout Klopp’s time at Liverpool. There’s also lots of what Atkinson does best: insightful and thoughtful reflection on the nature of contemporary football. Whether this is the nature of tickets and ticket prices, the state of TV football punditry, or why Liverpool fans (generally) don’t sing the national anthem, there’s much here for football fans and non-football fans alike to mull over and learn from.

But it’s also worth noting what’s not in the book. There’s no real prolonged deep dive into Klopp’s personality here. I don’t say that as a criticism, more as a matter of expectation-management for potential readers. This isn’t a biography or a character study, although there are elements of this, for example, in the chapter on Klopp’s ongoing footballing rivalry with Pep Guardiola.

Whole pages, even chapters pass without Klopp being mentioned. If you’re going into Transformer hoping to learn about Klopp’s upbringing, his playing career, his faith, you’ll likely be disappointed. But that’s fine, because Transformer isn’t that book.

So much of the book is awash with the warmth of friendship and humour and life.

Transformer is not a book about Jürgen Klopp. Obviously, ostensibly it is. Klopp’s tenure at Liverpool drives the book forward; provides its pulse. But this doesn’t explain why there is a whole chapter on the meaninglessness of football without Divock Origi. And it doesn’t explain the inclusion of sentences like the following: “27 November 2019: Knives Out is released, meaning Sadio Mané has competition for most flamboyant performance from a Liverpudlian in a calendar year.”

But it’s not even really a book about Liverpool, or football in general. Or Benoit Blanc. It’s a book about fun. About joy. About life, why it matters, why it’s good, and why it’s better with others.

It’s really a book about love. About loving a football club and loving and being loved by others in the midst of loving that football club.

Atkinson states up front that this book is about the people he has known and loved during Klopp’s time at Liverpool. It’s his version of this story. But in being his version, he allows it to be my version, too, and yours. “I am going to refer to people and places you may not know and we may not always trouble ourselves with descriptions. You don’t need to worry. That’s because these people, they are your friends. They are you.”

And this is why the book’s most emotionally fraught moments hit as hard as they do; because so much of the book is awash with the warmth of friendship and humour and life. When moments do stand out in stark relief from the very fun and love that Transformer is keen on have us believe in, they thereby make the case for their importance all the more clearly.

An insistence of the fundamental unseriousness of football is an act of gleeful rebellion. It is to play a different game.

Much has been said about Covid and football under Covid. Atkinson’s compassionate, understated treatment of it is genuinely beautiful at times. “People pass away, unmoored from time, separated from loves ones in the grimmest circumstances, and no one quite knows what to do.”

When reading Atkinson’s memories of the inner turmoil of his last interview with Klopp – “It was hard because I wanted to talk to him. At him. With him. I just wanted to list all these things has been part of with us, but, of course, he is more interested in you, in your world” – it’s hard not to be transported back to the sheer shock of his abrupt leaving.

In case it’s somehow not clear yet, let me state it here: I think Neil Atkinson is one the most compelling and insightful thinkers in and around modern football. This is in large part because of his insistence on what many forget: football is a game. It is supposed to be fun. It is supposed to be a fun game you enjoy with your mates.

We are in a world of nation-states and quasi-nation-states acquiring football clubs for political purposes. One with relentless discourse about the minutiae of every refereeing decision. A world where there is a constant, low-level feeling that I am yet again being ripped-off and taken advantage of for having the audacity to want to watch a football match. So, an insistence of the fundamental unseriousness of football is an act of gleeful rebellion. It is to play a different game.

“I don’t see anywhere near enough people writing about happiness in general, especially within the realm of football where grumpiness has become the order of the day.” Transformer is the apotheosis of modern footballing grumpiness. It is sincere, and earnest, and vulnerable. And I love it for this.

If you are looking for a comprehensive biography of Klopp, this isn’t it. This is something better.

When I spoke to him about Transformer, Atkinson said he wanted the book to show that football fans were normal, complex people. That they were accountants from Altringham, and theologians from Liverpool (if we can count theologians as ‘normal’ people). Transformer absolutely bristles with humanity.

Humans were made for community, for mates, for each other, and for last-minute Divock Origi winners. Humans were made for football.

If you want to remember why you fell in love with football – or if you want to understand why others fall in love with it – I can’t think of a better book to read than Transformer.